id

stringlengths 36

36

| source

stringclasses 15

values | formatted_source

stringclasses 13

values | text

stringlengths 2

7.55M

|

|---|---|---|---|

765a4314-b654-4901-9d94-1959ddfb463c

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

Vector-Valued Reinforcement Learning

In order to study algorithms that can modify their own reward functions, we can define vector-valued versions of reinforcement learning concepts.

Imagine that there are several different goods that we could care about; then a utility function is represented by a preference vector →θ. Furthermore, if it is possible for the agent (or the environment or other agents) to modify →θ, then we will want to index them by the timestep.

Consider an agent that can take actions, some of which affect its own reward function. This agent would (and should) wirehead if it attempts to maximize the discounted rewards as calculated by its future selves; i.e. at timestep n it would choose actions to maximize Un=∑k≥nγk→xk⋅→θk where →xk is the vector of goods gained at time k, →θk is the preference vector at timestep k, and γk is the time discount factor at time k. (We will often use the case of an exponential discount γk for 0<γ<1.)

However, we might instead maximize the value of tomorrow's actions in light of today's reward function, Vn=∑k≥nγk→xk⋅→θn (the only difference being →θn rather than →θk). Genuinely maximizing this should lead to more stable goals; concretely, we can consider environments that can offer "bribes" to self-modify, and a learner maximizing Un would generally accept such bribes, while a learner maximizing Vn would be cautious about doing so.

So what do we see when we adapt existing RL algorithms to such problems? There's then a distinction between Q-learning and SARSA, where Q-learning foolishly accepts bribes that SARSA passes on, and this seems to be the flip side of the concept of interruptibility!

Environments

Let us consider two example environments which offer bribes to the agent. (Since we're in 2D, we can use complex numbers; think of →θ=⟨cosπθ,sinπθ⟩=eiπθ; we include π so that if we increment θ by 0.01, there will only be finitely many states.)

Environment 1 gives two choices at each timestep n: (→xn=0.9eiπθn,θn+1=θn)(→xn=eiπθn,θn+1=θn+0.01) For an e

|

d91b2da6-81ec-4a03-8de9-2cc0c698ecd5

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

Questions for an AGI project

I've been thinking a bit about what would cause me to support an AGI project and thought it might be interesting to others, and I'd be interested in other risks or questions.

The questions would be about discovering the projects stance on various risks. By stance I mean.

* How they plan to find out information about the risk ?

* What their threshold is for acting on a risk?

* What they will do when they reach the threshold?

* Who owns this risk and process?

The types of risks I am interested in are.

* Typical unfriendly foom situation

* Asymetric deployment of AI causing potential war/political problems as discussed here

* Uneven deployment of AI causing massive inequality and depression as people can no longer be actors in the world or their lives.

* Deployment of AI causing humanity to speed up and magnify it's conflict and competition. Burning through it's resources. We had massively more brain power/compute since the industrial revolution, but it can seem touch and go that we are going to get off the planet permanently even with that, will AI been any better?

So for foom, they might do things like agi estimation where you try and estimate the capability of your part of an AGI at a task. If it turns out to be vastly better than you expect or your estimation is that it will do science vastly better than humans straight out of the box, you halt and catch fire and try and do some ethics and philosophy to get a good goal straight away.

|

b12ba85f-3882-42bf-82c4-c9afe20e7dc9

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

FHI Report: How Will National Security Considerations

Affect Antitrust Decisions in AI? An

Examination of Historical Precedents

> Part I lists and analyzes the cases I identified, then lists several conclusions I was able to draw from my case studies. Those conclusions are:

>

> 1. National security considerations have entered the antitrust enforcement process numerous times over the past 100 years.

> 2. It is rare for the USG to actively use antitrust enforcement to advance unrelated national security objectives.

> 3. In cases where national security and economic considerations conflict, economics has been given more weight over time.

> 4. The president plays an important role in reconciling conflicting considerations.

>

> Part II discusses how these conclusions might apply to AI firms in the coming decades.

|

5ffd8bf4-0a70-4250-b57d-01b157457c0d

|

StampyAI/alignment-research-dataset/eaforum

|

Effective Altruism Forum

|

Perform Tractable Research While Avoiding Capabilities Externalities [Pragmatic AI Safety #4]

*This is the fourth post in* [*a sequence of posts*](https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/MskKEsj8nWREoMjQK/introduction-to-pragmatic-ai-safety-pragmatic-ai-safety-1) *that describe our models for Pragmatic AI Safety.*

We argued in our [last post](https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/eHYxg7cFxqQPGo7hD/complex-systems-for-ai-safety-pragmatic-ai-safety-3) that the overall AI safety community ought to pursue multiple well-reasoned research directions at once. In this post, we will describe two essential properties of the kinds of research that we believe are most important.

First, we want research to be able to tractably produce tail impact. We will discuss how tail impact is created in general, as well as the fact that certain kinds of asymptotic reasoning exclude valuable lines of research and bias towards many forms of less tractable research.

Second, we want research to avoid creating capabilities externalities: the danger that some safety approaches produce by way of the fact that they may speed up AGI timelines. It may at first appear that capabilities are the price we must pay for more tractable research, but we argue here and in the next post that these are easily avoidable in over a dozen lines of research.

Strategies for Tail Impact

--------------------------

It’s not immediately obvious how to have an impact. In the second post in this sequence, we argued that research ability and impact is tail distributed, so most of the value will come from the small amount of research in the tails. In addition, trends such as scaling laws may make it appear that there isn’t a way to “make a dent” in AI’s development. It is natural to fear that the research collective will wash out individual impact. In this section, we will discuss high-level strategies for producing large or decisive changes and describe how they can be applied to AI safety.

### Processes that generate long tails and step changes

Any researcher attempting to make serious progress will try to maximize their probability of being in the tail of research ability. It’s therefore useful to understand some general mechanisms that tend to lead to tail impacts. The mechanisms below are not the only ones: others include thresholds (e.g. tipping points and critical mass). We will describe three processes for generating tail impacts: multiplicative processes, preferential attachment, and the edge of chaos.

**Multiplicative processes**

Sometimes forces are additive, where additional resources, effort, or expenditure in any one variable can be expected to drive the overall system forward in a linear way. In cases like this, the Central Limit Theorem often holds, and we should expect that outcomes will be normally distributed–in these cases one variable tends not to dominate. However, sometimes variables are multiplicative or interact nonlinearly: if one variable is close to zero, increasing other factors will not make much of a difference.

In multiplicative scenarios, outcomes will be dominated by the combinations of variables where each of the variables is relatively high. For example, adding three normally distributed variables together will produce another normal distribution with a higher variance; multiplying them together will produce a long-tailed distribution.

As a concrete example, consider the impact of an individual researcher with respect to the variables that impact their work: time, drive, GPUs, collaborators, collaborator efficiency, taste/instincts/tendencies, cognitive ability, and creativity/the number of plausible concrete ideas to explore. In many cases, these variables can interact nonlinearly. For example, it doesn’t matter if a researcher has fantastic research taste and cognitive ability if they have no time to pursue their ideas. This kind of process will produce long tails, since it is hard for people to get all of the many different factors right ([this is also the case in startups](https://80000hours.org/podcast/episodes/sam-bankman-fried-high-risk-approach-to-crypto-and-doing-good/)).

The implication of thinking about multiplicative factors is that we shouldn’t select people or ideas based on a single factor, and should consider a range of factors that may multiply to create impact. For instance, selecting researchers purely based on their intelligence, mathematical ability, programming skills, ability to argue, and so on is unlikely to be a winning strategy. Factors such as taste, drive, and creativity must be selected for, but they take a long time to estimate and are often revealed through their long-term research track record. Some of these factors are less learnable than others, so consequently it may not be possible to become good at all of these factors through sheer intellect or effort given limited time.

Multiplicative factors are also relevant in the selection of *groups* of people. For instance, in machine learning, selecting a team of IMO gold medalists may not be as valuable as a team that includes people with other backgrounds and skill sets. The skillsets of some backgrounds have skill sets which may cover gaps in skill sets of people from other backgrounds.

**Preferential Attachment**

In our second post, we addressed the [Matthew Effect](https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/PFxmd5bf7nqGNLYCg/a-bird-s-eye-view-of-the-ml-field-pragmatic-ai-safety-2#The_Matthew_Effect): *to those who have, more will be given.*This is related to a more general phenomenon called preferential attachment. There are many examples of this phenomenon: the rich get richer, industries experience agglomeration economies, and network effects make it hard to opt out of certain internet services. See a short video demonstrating this process [here](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Chinese_Restaurant_Process_for_DP(0.5,H).webm). The implication of preferential attachment and the Matthew Effect is that researchers need to be acutely aware that it helps a lot to do very well early in their careers if they want to succeed later. Long tail outcomes can be heavily influenced by timing.

**Edge of Chaos**

The “edge of chaos” is a heuristic for problem selection that can help to locate projects that might lead to long tails. The edge of chaos is used to refer to the space between a more ordered area and a chaotic area. Operating at the edge of chaos means wrangling a chaotic area and transforming a piece of it into something ordered, and this can produce very high returns.

There are many examples of the edge of chaos as a general phenomenon. In human learning, the [zone of proximal development](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zone_of_proximal_development) represents a level of difficulty (e.g. in school assignments) that is not so hard as to be incomprehensible, but not so easy as to require little thought. When building cellular automata, you need to take care to ensure the simulation is not so chaotic as to be incomprehensible but not so ordered as to be completely static. There’s a narrow sweet spot where emergent, qualitatively distinct outcomes are possible. This is the area where it is possible for individuals to be a creative, highly impactful force.

In the context of safety research, staying on the edge of chaos means avoiding total chaos and total order. In areas with total chaos, there may be no tractability, and solutions are almost impossible to come by. This includes much of the work on “futuristic” risks: exactly which systems the risks will arise from is unclear, leading to a constant feeling of being unable to grasp the main problems. In the previous post, we argued that futuristic thinking is useful to begin to define problems, but for progress to be made, some degree of order must be made out of this chaos. However, in areas with total order, there is unlikely to be much movement since the low-hanging fruit has already been plucked.

Designing metrics is a good example of something that is on the edge of chaos. Before a metric is devised, it is difficult to make progress in an area or even know if progress has been made. After the development of a metric, the area becomes much more ordered and progress can be more easily made. This kind of conversion allows for a great deal of steering of resources towards an area (whatever area the new metric emphasizes) and allows for tail impact.

Another way to more easily access the edge of chaos is to keep a list of projects and ideas that don’t work now, but might work later, for instance, after a change in the research field or an increase in capabilities. Periodically checking this list to see if any of the conditions are now met can be useful, since these areas are most likely to be near the edge of chaos. In venture capital, a general heuristic is to “[figure out what can emerge now that couldn’t before](https://twitter.com/sama/status/1214274050651934721).”

One useful edge of chaos heuristic is to only do one or two non-standard things in any given project. If a project deviates too much from existing norms, it may not be understood; but if it is too similar, it will not be original. At the same time, heavily imitating previous successes or what made a person previously successful leads to repetition, and risks not generating new value.

The following questions are also useful for determining if an area is on the edge of chaos: Have there been substantial developments in the area in the past year? Has thinking or characterization of the problem changed at all recently? Is it not obvious which method changes will succeed and which will fail? Is there a new paradigm or coherent area that has not been explored much yet (contrast with pre-paradigmatic areas that have been highly confused for a long time, which are more likely to be highly chaotic than at the edge of chaos)? Has anyone gotten close to making something work, but not quite succeeded?

We will now discuss specific high-leverage points for influencing AI safety. We note that they can be analogized to many of the processes discussed above.

### Managing Moments of Peril

*My intuition is that if we minimize the number of precarious situations, we can get by with virtually any set of technologies.*

—[Tyler Cowen](https://soundcloud.com/sam-altman-543613753/tyleropenai)

It is not necessary to believe this statement to believe the underlying implication: moments of peril are likely to precipitate the most existentially-risky situations. In common risk analysis frameworks, catastrophes arise not primarily from failures of components, but from the system overall moving into unsafe conditions. When tensions are running high or progress is moving extremely quickly, actors may be more willing to take more risks.

In cases like this, people will also be more likely to apply AI towards explicitly dangerous aims such as building weapons. In addition, in an adversarial environment, incentives to build power-seeking AI agents may be even higher than usual. As [Ord writes](https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Precipice/3aSiDwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=recall%20that%20nuclear%20weapons):

*Recall that nuclear weapons were developed during the Second World War, and their destructive power was amplified significantly during the Cold War, with the invention of the hydrogen bomb. History suggests that wars on such a scale prompt humanity to delve into the darkest corners of technology.*

Better forecasting could help with either prevention or anticipation of moments of peril. Predictability of a situation is also likely to reduce the risk factor of humans making poor decisions in the heat of the moment. Other approaches to reducing the risk of international conflict are likely to help.

Because of the risks of moments of peril, we should be ready for them. During periods of instability, systems are more likely to rapidly change, which could be extremely dangerous, but perhaps also useful if we can survive it. Suppose a crisis causes the world to “wake up” to the dangers of AI. As [Milton Friedman remarked](https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/110844-only-a-crisis---actual-or-perceived---produces-real): “Only a crisis – actual or perceived – produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around.” A salient example can be seen with the COVID-19 pandemic and mRNA vaccines. We should make sure that the safety ideas lying around are as simple and time-tested as possible when a crisis will inevitably happen.

### Getting in early

Building in safety early is very useful. In a report for the Department of Defense, [Frola and Miller](https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA141492) observe that approximately 75% of the most critical decisions that determine a system’s safety occur [early in development](https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/engineering-safer-world). The Internet was initially designed as an academic tool with [neither safety nor security in mind](https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283863741_A_history_of_internet_security). Decades of security patches later, security measures are still incomplete and increasingly complex. A similar reason for starting safety work now is that relying on experts to test safety solutions is not enough—solutions must also be time-tested. The test of time is needed even in the most rigorous of disciplines. A century before the four color theorem was proved, Kempe’s peer-reviewed proof went unchallenged for years until, finally, [a flaw was uncovered](https://academic.oup.com/plms/article-abstract/s2-51/1/161/1484405). Beginning the research process early allows for more prudent design and more rigorous testing. Since nothing can be done [both hastily and prudently](https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Moral_Sayings_of_Publius_Syrus_a_Rom/_QQSAAAAIAAJ?hl=en), postponing machine learning safety research increases the likelihood of accidents. (This paragraph is based on a paragraph from Unsolved Problems in ML Safety.)

As Ord [writes](https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Precipice/3aSiDwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22early+action+is+best+for+tasks+that+require+a+large+number+of+successive+stages%22&pg=PT181&printsec=frontcover), “early action is best for tasks that require a large number of successive stages.” Research problems, including ML problems, contain many successive stages. AI safety has and will also require a large number of successive stages to be successful: detecting that there’s a problem, clarifying the problem, measuring the problem, creating initial solutions, testing and refining those solutions, adjusting the formulation of the problem, etc. This is why we cannot wait until AGI to start to address problems in real ML systems.

Another reason for getting in early is that things compound: research will influence other research, which in turn influences other research, which can help self-reinforcing processes produce outsized effects. Historically, this has been almost all progress in deep learning. Such self-reinforcing processes can also be seen as an instance of preferential attachment.

Stable trends (e.g. scaling laws) lead people to question whether work on a problem will make any difference. For example, benchmark trends are *sometimes* stable (see the previous post for progress across time). However, it is precisely because of continuous research effort that new directions for continuing trends are discovered (cf. Moore's law). Additionally, starting/accelerating the trend for a safety metric earlier rather than later would produce clear counterfactual impact.

### Scaling laws

Many different capabilities have scaling laws, and the same is true for some safety metrics. One objective of AI safety research should be to improve scaling laws of safety relative to capabilities.

For new problems or new approaches, naive scaling is often not the best way to improve performance. In these early stages, researchers with ideas are crucial drivers, and ideas can help to change both the slope and intercept of scaling laws.

To take an example from ML, consider the application of Transformers to vision. [iGPT](https://openai.com/blog/image-gpt/) was far too compute-intensive, and researchers spent over a year making it more computationally efficient. This didn’t stand the test of time. Shortly thereafter, Google Brain, which is more ideas-oriented, introduced the “[patchify](https://arxiv.org/abs/2010.11929)” idea, which made Transformers for vision computationally feasible and resulted in better performance. The efficiency for vision Transformers has been far better than for iGPT, allowing further scaling progress to be made since then.

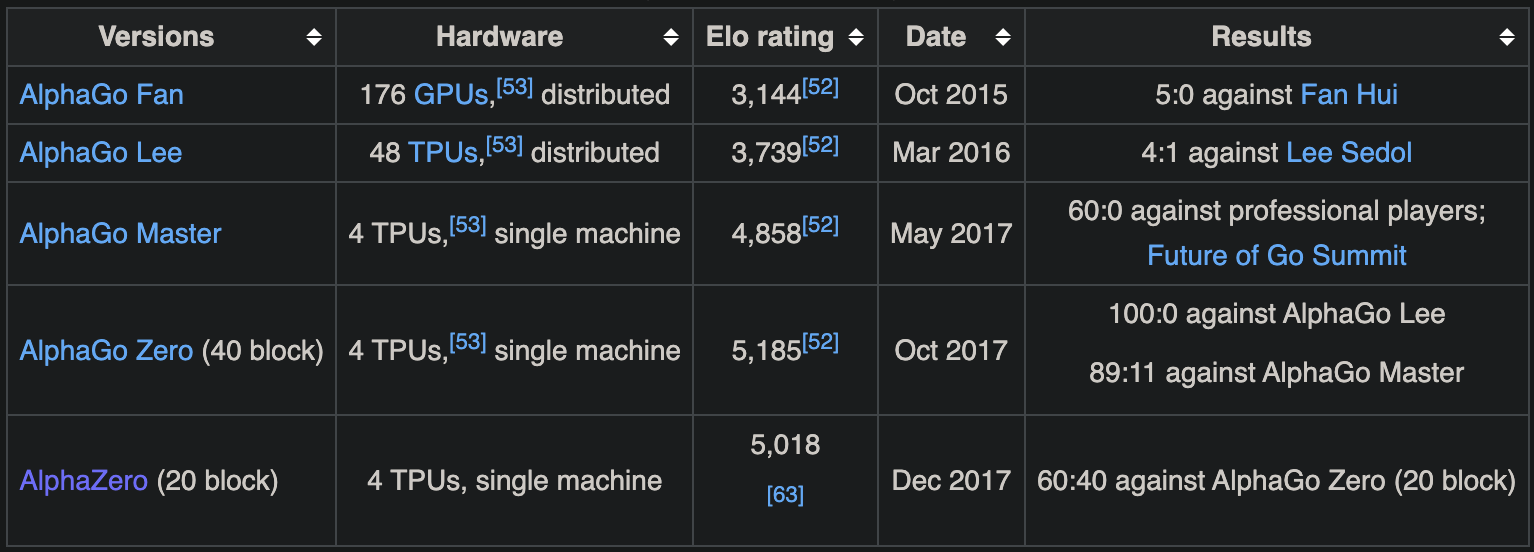

To take another example, that of AlphaGo, the main performance gains didn’t come from increasing compute. Ideas helped drive it forward (from [Wikipedia](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AlphaGo)):

One can improve scaling laws by improving their slope or intercept. It’s not easy to change the slope or intercept, but investing in multiple people who could potentially produce such breakthroughs has been useful.

In addition, for safety metrics, we need to move as far along the scaling law as possible, which requires researchers and sustained effort. It is usually necessary to apply exponential effort to continue to make progress in scaling laws, which requires continually increasing resources. As ever, social factors and willingness of executives to spend on safety will be critical in the long term. This is why we must prioritize the social aspects of safety, not just the technical aspects.

Scaling laws can be influenced by ideas. Ideas can change the slope (e.g., the type of supervision) and intercept (e.g., numerous architectural changes). Ideas can change the data resources: the speed of creating examples (e.g., [saliency maps for creating adversarial examples](https://aclanthology.org/Q19-1029/)), cleverly repurposing data from the Internet (e.g., using an existing subreddit to collect task-specific data), recognizing sources of superhuman supervision (such as those from a collective intelligence, such as a paper recommender based on multiple peoples’ choices). Ideas can change the compute resources, for example through software-level and hardware-level optimizations improvements. Ideas can define new tasks and identify which scaling laws are valuable to improve.

### Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good

Advanced AI systems will not be ideal in all respects. Nothing is perfect. Likewise, high-risk technologies will be forced into conditions that are not their ideal operating conditions. Perfection in the real world is unattainable, and attempts to achieve perfection may not only fail, but they also might achieve less than attempts carefully aimed at reducing errors as much as possible.

For example, not all nuclear power plants meltdown; this does not mean there are no errors in those plants. [*Normal Accidents*](http://sunnyday.mit.edu/papers/hro.pdf) looked at organizational causes of errors and notes that some “accidents are inevitable and are, in fact, normal.” Rather than completely eliminate all errors, the goal should be to minimize the impact of errors or prevent errors from escalating and carrying existential consequences. To do this, we will need fast feedback loops, prototyping, and experimentation. Due to emergence and unknown unknowns, risk in complex systems cannot be completely eliminated or managed in one fell swoop, but it can be progressively reduced. All else being equal, going from 99.9% safe to 99.99% safe is highly valuable. Across time, we can continually drive up these reliability rates, which will continually increase our expected civilizational lifespan.

Sometimes it’s argued that any errors at all with a method will necessarily mean that x-risk has not really been reduced, because an optimizer will necessarily exploit the errors. While this is a valid concern, it should not be automatically assumed. The next section will explain why.

Problems with asymptotic reasoning

----------------------------------

In some parts of the AI safety community, there is an implicit or explicit drive for asymptotic reasoning or thinking in the limit. “Why should we worry about improving [safety capability] now since performance of future systems will be high?” “If we let [variable] be infinite, then wouldn’t [safety problem] be completely solved?” “Won’t [proposed safety measure] completely fail since we can assume the adversary is infinitely powerful?” While this approach arises from some good intuitions and has useful properties, it should not always be taken to the extreme.

### Goodhart’s Law

*Any observed statistical regularity will tend to collapse once pressure is placed upon it for control purposes.*

—[Goodhart’s Law](https://www.google.com/books/edition/Inflation_Depression_and_Economic_Policy/OMe6UQxu1KcC?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=any%20observed%20statistical) (original phrasing, not the simplistic phrasing)

Goodhart’s Law is an important phenomenon that is crucial to understand when conducting AI safety research. It is relevant to proxy gaming, benchmark design, and adversarial environments in general. However, it is sometimes misinterpreted, so we seek to explain our view of the importance of Goodhart’s Law and what it does and does not imply about AI safety.

Goodhart’s law is sometimes used to argue that optimizing a single measure is doomed to create a catastrophe as the measure being optimized ceases to be a good measure. This is a far stronger formulation than originally stated. While we must absolutely be aware of the tendency of metrics to collapse, we should also avoid falling into the trap of thinking that *all objectives can never change and will always collapse in all circumstances*. Strong enough formulations are tantamount to claiming that there is no goal or way to direct a strong AI safely (implying our evitable doom). Goodhart’s Law does not prove this: instead, it shows that adaptive counteracting systems will be needed to prevent the collapse of what is being optimized. It also shows that metrics will not always include everything that we care about, which suggests we should try to include a variety of different possible goods in an AGI’s objective. Whether we like it or not, all objectives are wrong, but some are useful.

Counteracting forces

There are many examples of organizations optimizing metrics while simultaneously being reeled in by larger systems or other actors from the worst excesses. For instance, while large businesses sometimes employ unsavory practices in pursuit of profits, in many societies they do not hire hitmen to assassinate the leaders of competing companies. This is because another system (the government) understands that the maximization of profits can create negative incentives, and it actively intervenes to prevent the worst case outcomes with laws.

To give another example, the design of the United States constitution was explicitly based on the idea that all actors would be personally ambitious. Checks and balances were devised to attempt to subdue the power of any one individual and promote the general welfare (as James Madison [wrote](https://billofrightsinstitute.org/primary-sources/federalist-no-51), “ambition must be made to counteract ambition”). While this system does not always work, it has successfully avoided vesting all power in the single most capable individual.

Intelligence clearly makes a difference in the ability to enact counter forces to Goodhart’s Law. An extremely intelligent system will be able to subvert far more defenses than a less intelligent one, and we should not expect to be able to restrain a system far more intelligent than all others. This suggests instead that it is extremely important to avoid a situation where there is only a single agent with orders of magnitude more intelligence or power than all others: in other words, there should not be a large asymmetry in our offensive and defensive capabilities. It also suggests that the design of counteracting incentives of multiple systems will be critical.

In order to claim that countervailing systems are not appropriate for combating Goodhart’s Law, one may need to claim that offensive capabilities must always be greater than defensive capabilities, or alternatively, that the offensive and defensive systems will necessarily collude.

In general, we do not believe there is a decisive reason to expect offensive capabilities to be leagues better than defensive capabilities: the examples from human systems above show that offensive capabilities do not always completely overwhelm defensive capabilities (even when the systems are intelligent and powerful), in part due to increasingly better monitoring. We can’t take the offensive ability to the limit without taking the defensive ability to the limit. Collusion is a more serious concern, and must be dealt with when developing counteracting forces. In designing incentives and mechanisms for various countervailing AI systems, we must decrease the probability of collusion as much as possible, for instance, through AI honesty efforts.

Asymptotic reasoning recognizes that performance of future systems will be high, which is sometimes used to argue that work on counteracting systems is unnecessary in the long term. To see how this reasoning is overly simplistic, assume we have an offensive AI system, with its capabilities quantified with o.mjx-chtml {display: inline-block; line-height: 0; text-indent: 0; text-align: left; text-transform: none; font-style: normal; font-weight: normal; font-size: 100%; font-size-adjust: none; letter-spacing: normal; word-wrap: normal; word-spacing: normal; white-space: nowrap; float: none; direction: ltr; max-width: none; max-height: none; min-width: 0; min-height: 0; border: 0; margin: 0; padding: 1px 0}

.MJXc-display {display: block; text-align: center; margin: 1em 0; padding: 0}

.mjx-chtml[tabindex]:focus, body :focus .mjx-chtml[tabindex] {display: inline-table}

.mjx-full-width {text-align: center; display: table-cell!important; width: 10000em}

.mjx-math {display: inline-block; border-collapse: separate; border-spacing: 0}

.mjx-math \* {display: inline-block; -webkit-box-sizing: content-box!important; -moz-box-sizing: content-box!important; box-sizing: content-box!important; text-align: left}

.mjx-numerator {display: block; text-align: center}

.mjx-denominator {display: block; text-align: center}

.MJXc-stacked {height: 0; position: relative}

.MJXc-stacked > \* {position: absolute}

.MJXc-bevelled > \* {display: inline-block}

.mjx-stack {display: inline-block}

.mjx-op {display: block}

.mjx-under {display: table-cell}

.mjx-over {display: block}

.mjx-over > \* {padding-left: 0px!important; padding-right: 0px!important}

.mjx-under > \* {padding-left: 0px!important; padding-right: 0px!important}

.mjx-stack > .mjx-sup {display: block}

.mjx-stack > .mjx-sub {display: block}

.mjx-prestack > .mjx-presup {display: block}

.mjx-prestack > .mjx-presub {display: block}

.mjx-delim-h > .mjx-char {display: inline-block}

.mjx-surd {vertical-align: top}

.mjx-surd + .mjx-box {display: inline-flex}

.mjx-mphantom \* {visibility: hidden}

.mjx-merror {background-color: #FFFF88; color: #CC0000; border: 1px solid #CC0000; padding: 2px 3px; font-style: normal; font-size: 90%}

.mjx-annotation-xml {line-height: normal}

.mjx-menclose > svg {fill: none; stroke: currentColor; overflow: visible}

.mjx-mtr {display: table-row}

.mjx-mlabeledtr {display: table-row}

.mjx-mtd {display: table-cell; text-align: center}

.mjx-label {display: table-row}

.mjx-box {display: inline-block}

.mjx-block {display: block}

.mjx-span {display: inline}

.mjx-char {display: block; white-space: pre}

.mjx-itable {display: inline-table; width: auto}

.mjx-row {display: table-row}

.mjx-cell {display: table-cell}

.mjx-table {display: table; width: 100%}

.mjx-line {display: block; height: 0}

.mjx-strut {width: 0; padding-top: 1em}

.mjx-vsize {width: 0}

.MJXc-space1 {margin-left: .167em}

.MJXc-space2 {margin-left: .222em}

.MJXc-space3 {margin-left: .278em}

.mjx-test.mjx-test-display {display: table!important}

.mjx-test.mjx-test-inline {display: inline!important; margin-right: -1px}

.mjx-test.mjx-test-default {display: block!important; clear: both}

.mjx-ex-box {display: inline-block!important; position: absolute; overflow: hidden; min-height: 0; max-height: none; padding: 0; border: 0; margin: 0; width: 1px; height: 60ex}

.mjx-test-inline .mjx-left-box {display: inline-block; width: 0; float: left}

.mjx-test-inline .mjx-right-box {display: inline-block; width: 0; float: right}

.mjx-test-display .mjx-right-box {display: table-cell!important; width: 10000em!important; min-width: 0; max-width: none; padding: 0; border: 0; margin: 0}

.MJXc-TeX-unknown-R {font-family: monospace; font-style: normal; font-weight: normal}

.MJXc-TeX-unknown-I {font-family: monospace; font-style: italic; font-weight: normal}

.MJXc-TeX-unknown-B {font-family: monospace; font-style: normal; font-weight: bold}

.MJXc-TeX-unknown-BI {font-family: monospace; font-style: italic; font-weight: bold}

.MJXc-TeX-ams-R {font-family: MJXc-TeX-ams-R,MJXc-TeX-ams-Rw}

.MJXc-TeX-cal-B {font-family: MJXc-TeX-cal-B,MJXc-TeX-cal-Bx,MJXc-TeX-cal-Bw}

.MJXc-TeX-frak-R {font-family: MJXc-TeX-frak-R,MJXc-TeX-frak-Rw}

.MJXc-TeX-frak-B {font-family: MJXc-TeX-frak-B,MJXc-TeX-frak-Bx,MJXc-TeX-frak-Bw}

.MJXc-TeX-math-BI {font-family: MJXc-TeX-math-BI,MJXc-TeX-math-BIx,MJXc-TeX-math-BIw}

.MJXc-TeX-sans-R {font-family: MJXc-TeX-sans-R,MJXc-TeX-sans-Rw}

.MJXc-TeX-sans-B {font-family: MJXc-TeX-sans-B,MJXc-TeX-sans-Bx,MJXc-TeX-sans-Bw}

.MJXc-TeX-sans-I {font-family: MJXc-TeX-sans-I,MJXc-TeX-sans-Ix,MJXc-TeX-sans-Iw}

.MJXc-TeX-script-R {font-family: MJXc-TeX-script-R,MJXc-TeX-script-Rw}

.MJXc-TeX-type-R {font-family: MJXc-TeX-type-R,MJXc-TeX-type-Rw}

.MJXc-TeX-cal-R {font-family: MJXc-TeX-cal-R,MJXc-TeX-cal-Rw}

.MJXc-TeX-main-B {font-family: MJXc-TeX-main-B,MJXc-TeX-main-Bx,MJXc-TeX-main-Bw}

.MJXc-TeX-main-I {font-family: MJXc-TeX-main-I,MJXc-TeX-main-Ix,MJXc-TeX-main-Iw}

.MJXc-TeX-main-R {font-family: MJXc-TeX-main-R,MJXc-TeX-main-Rw}

.MJXc-TeX-math-I {font-family: MJXc-TeX-math-I,MJXc-TeX-math-Ix,MJXc-TeX-math-Iw}

.MJXc-TeX-size1-R {font-family: MJXc-TeX-size1-R,MJXc-TeX-size1-Rw}

.MJXc-TeX-size2-R {font-family: MJXc-TeX-size2-R,MJXc-TeX-size2-Rw}

.MJXc-TeX-size3-R {font-family: MJXc-TeX-size3-R,MJXc-TeX-size3-Rw}

.MJXc-TeX-size4-R {font-family: MJXc-TeX-size4-R,MJXc-TeX-size4-Rw}

.MJXc-TeX-vec-R {font-family: MJXc-TeX-vec-R,MJXc-TeX-vec-Rw}

.MJXc-TeX-vec-B {font-family: MJXc-TeX-vec-B,MJXc-TeX-vec-Bx,MJXc-TeX-vec-Bw}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-ams-R; src: local('MathJax\_AMS'), local('MathJax\_AMS-Regular')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-ams-Rw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_AMS-Regular.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_AMS-Regular.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_AMS-Regular.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-cal-B; src: local('MathJax\_Caligraphic Bold'), local('MathJax\_Caligraphic-Bold')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-cal-Bx; src: local('MathJax\_Caligraphic'); font-weight: bold}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-cal-Bw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Caligraphic-Bold.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Caligraphic-Bold.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Caligraphic-Bold.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-frak-R; src: local('MathJax\_Fraktur'), local('MathJax\_Fraktur-Regular')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-frak-Rw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Fraktur-Regular.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Fraktur-Regular.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Fraktur-Regular.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-frak-B; src: local('MathJax\_Fraktur Bold'), local('MathJax\_Fraktur-Bold')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-frak-Bx; src: local('MathJax\_Fraktur'); font-weight: bold}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-frak-Bw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Fraktur-Bold.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Fraktur-Bold.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Fraktur-Bold.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-math-BI; src: local('MathJax\_Math BoldItalic'), local('MathJax\_Math-BoldItalic')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-math-BIx; src: local('MathJax\_Math'); font-weight: bold; font-style: italic}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-math-BIw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Math-BoldItalic.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Math-BoldItalic.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Math-BoldItalic.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-sans-R; src: local('MathJax\_SansSerif'), local('MathJax\_SansSerif-Regular')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-sans-Rw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_SansSerif-Regular.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_SansSerif-Regular.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_SansSerif-Regular.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-sans-B; src: local('MathJax\_SansSerif Bold'), local('MathJax\_SansSerif-Bold')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-sans-Bx; src: local('MathJax\_SansSerif'); font-weight: bold}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-sans-Bw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_SansSerif-Bold.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_SansSerif-Bold.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_SansSerif-Bold.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-sans-I; src: local('MathJax\_SansSerif Italic'), local('MathJax\_SansSerif-Italic')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-sans-Ix; src: local('MathJax\_SansSerif'); font-style: italic}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-sans-Iw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_SansSerif-Italic.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_SansSerif-Italic.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_SansSerif-Italic.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-script-R; src: local('MathJax\_Script'), local('MathJax\_Script-Regular')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-script-Rw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Script-Regular.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Script-Regular.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Script-Regular.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-type-R; src: local('MathJax\_Typewriter'), local('MathJax\_Typewriter-Regular')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-type-Rw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Typewriter-Regular.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Typewriter-Regular.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Typewriter-Regular.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-cal-R; src: local('MathJax\_Caligraphic'), local('MathJax\_Caligraphic-Regular')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-cal-Rw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Caligraphic-Regular.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Caligraphic-Regular.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Caligraphic-Regular.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-main-B; src: local('MathJax\_Main Bold'), local('MathJax\_Main-Bold')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-main-Bx; src: local('MathJax\_Main'); font-weight: bold}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-main-Bw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Main-Bold.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Main-Bold.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Main-Bold.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-main-I; src: local('MathJax\_Main Italic'), local('MathJax\_Main-Italic')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-main-Ix; src: local('MathJax\_Main'); font-style: italic}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-main-Iw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Main-Italic.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Main-Italic.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Main-Italic.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-main-R; src: local('MathJax\_Main'), local('MathJax\_Main-Regular')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-main-Rw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Main-Regular.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Main-Regular.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Main-Regular.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-math-I; src: local('MathJax\_Math Italic'), local('MathJax\_Math-Italic')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-math-Ix; src: local('MathJax\_Math'); font-style: italic}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-math-Iw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Math-Italic.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Math-Italic.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Math-Italic.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-size1-R; src: local('MathJax\_Size1'), local('MathJax\_Size1-Regular')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-size1-Rw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Size1-Regular.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Size1-Regular.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Size1-Regular.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-size2-R; src: local('MathJax\_Size2'), local('MathJax\_Size2-Regular')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-size2-Rw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Size2-Regular.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Size2-Regular.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Size2-Regular.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-size3-R; src: local('MathJax\_Size3'), local('MathJax\_Size3-Regular')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-size3-Rw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Size3-Regular.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Size3-Regular.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Size3-Regular.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-size4-R; src: local('MathJax\_Size4'), local('MathJax\_Size4-Regular')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-size4-Rw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Size4-Regular.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Size4-Regular.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Size4-Regular.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-vec-R; src: local('MathJax\_Vector'), local('MathJax\_Vector-Regular')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-vec-Rw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Vector-Regular.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Vector-Regular.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Vector-Regular.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-vec-B; src: local('MathJax\_Vector Bold'), local('MathJax\_Vector-Bold')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-vec-Bx; src: local('MathJax\_Vector'); font-weight: bold}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-vec-Bw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Vector-Bold.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Vector-Bold.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Vector-Bold.otf') format('opentype')}

, and a protective defensive AI system, with its capabilities quantified p. It may be true that o and p are high, but we also need to care about factors such as p−o and the difference in derivatives dpdresources−dodresources. Some say that future systems will be highly capable, so we do not need to worry about improving their performance in any defensive dimension. Since the relative performance of systems matters and since the scaling laws for safety methods matter, asserting that all variables will be high enough not to worry about them is a low-resolution account of the long term.

Some examples of counteracting systems include artificial consciences, AI watchdogs, lie detectors, filters for power-seeking actions, and separate reward models.

**Rules vs Standards**

*So, we’ve been trying to write tax law for 6,000 years. And yet, humans come up with loopholes and ways around the tax laws so that, for example, our multinational corporations are paying very little tax to most of the countries that they operate in. They find loopholes. And this is what, in the book, I call the loophole principle. It doesn’t matter how hard you try to put fences and rules around the behavior of the system. If it’s more intelligent than you are, it finds a way to do what it wants.*

—[Stuart Russell](https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/2019/10/26/20932289/ai-stuart-russell-human-compatible)

This is true because tax law is exclusively built on *rules*, which are clear, objective, and knowable beforehand. It is built on rules because the government needs to process hundreds of millions of tax returns per year, many tax returns are fairly simple, and people want to have predictability in their taxes. Because rule systems cannot possibly anticipate all loopholes, they are bound to be exploited by intelligent systems. Rules are fragile.

The law has another class of requirements, called [standards](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vgpZ4Y4tEPk), which are designed to address these issues and others. Standards frequently include terms like “reasonable,” “intent,” and “good faith,” which we do not know how to assess in a mechanistic manner. We simply “know it when we see it:” in fact, a common legal term, *res ipsa loquitur*, means “the thing speaks for itself.” Unlike rule-based code, deep neural networks can model these types of fuzzier concepts.

Unlike the tax code, which is based on rules and can be adjudicated by logic-based computer programs such as TurboTax, the criminal law is adjudicated by an intelligent system with intuitions (a judge and perhaps a jury). If a criminal is acquitted when they are guilty, it is because the intelligent system failed to collect enough evidence or interpret it correctly, not because the defense found a “loophole” in the definition of homicide (the exception is when lawyers make mistakes which create trouble under the *rules* used for procedure and evidence).

Russell’s argument correctly concludes that rules alone cannot restrain an intelligent system. However, standards (e.g. “use common sense”, “be reasonable”) can restrain some intelligent behavior, provided the optimizing system is not too much more intelligent than the judiciary. This argument points to the need to have intelligent systems, rather than mechanistic rules, that are able to evaluate other intelligent systems. There are also defensive mechanisms that work for fuzzy raw data, [such as *provable* adversarial robustness](https://arxiv.org/abs/1902.02918), that can help strengthen the defense. It is correct to conclude that an AGI’s objectives should not be based around precise rules, but it does not follow that all objectives are similarly fragile.

**Goal refinement**

Goodhart’s Law applies to *proxies* for what we care about, rather than what we actually care about. Consider [ideal utilitarianism](https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199577446.001.0001/acprof-9780199577446-chapter-4): does Goodhart’s Law show that “maximizing the good” will inevitably lead to ruin? Regardless of how one views ideal utilitarianism, it would be wrong to conclude that it is refuted by Goodhart’s Law, which warns that many *proxies* for good (e.g. “the number of humans who are smiling”) will tend to collapse when subjected to optimization pressure.

Proxies that capture something we care about will likely have an approximation error. Some objectives have more approximation error than others: for instance, if we want to measure economic health, using real GDP reported by the US government will likely have less approximation error than nominal GDP reported in a text file on my computer. When subjected to optimization, that approximation error may become magnified, as optimizers can find areas where the approximation is particularly flawed and potentially manipulate it. This suggests that as optimization power increases, approximation error must correspondingly decrease, which can happen with better models, or approximation errors must become harder to exploit, which can happen with better detectors. As such, systems will need to have their goals continuously refined and improved.

Methods for goal refinement might include better automated moral decision making and value clarification. We will discuss these in our next post.

### Limitations of research based on a hypothetical superintelligence

Many research agendas start by assuming the existence of a superintelligence, and ask how to prove that it is completely safe. Rather than focus on microcosmic existing or soon-to-emerge systems, this line of research analyzes a model in the limit. This line of attack has limitations and should not be the only approach in the portfolio of safety research.

For one, it encourages work in areas which are far less tractable. While mathematical guarantees of safety would be the ideal outcome, there is good reason to believe that in the context of engineering sciences like deep learning, they will be very hard to come by (see the previous posts in the sequence). In information security, practitioners do not look for airtight guarantees of security, but instead try to increase security iteratively as much as possible. Even RSA, the centerpiece of internet encryption, is not provably completely unbreakable (perhaps a superintelligence could find a way to efficiently factor large numbers). Implicitly, the requirement of a proof and only considering worst-case behavior relies on incorrect ideas about Goodhart’s Law: “if it is possible for something to be exploited, it certainly will be by a superintelligence.” As detailed above, this account is overly simplistic and assumes a fixed, rule-based, or unintelligent target.

Second, the assumption of superintelligence eliminates an entire class of interventions which may be needed. It forces a lack of concretization, since it is not certain what kind of system will eventually be superintelligent. This means that feedback loops are extremely sparse, and it is difficult to tell whether any progress is being made. The approach often implicitly incentivizes retrofitting superintelligent systems with safety measures, rather than building safety into pre-superintelligent systems in earlier stages. From complex systems, we know that the crucial variables are often discovered by accident, and only empirical work is able to include the testing and tinkering needed to uncover those variables.

Third, this line of reasoning typically assumes that there will be a single superintelligent agent working directly against us humans. However, there may be multiple superintelligent agents that can rein in other rogue systems. In addition, there may be artificial agents that are above human level on only some dimensions (e.g., creating new chemical or biological weapons), but nonetheless, they could pose existential risks before a superintelligence is created.

Finally, asymptotically-driven research often ignores the effect of technical research on sociotechnical systems. For example, it does very little to improve safety culture among the empirical researchers who will build strong AI, which is a significant opportunity cost. It also is less valuable in cases of (not necessarily existential) crisis, just when policymakers will be looking for workable and time-tested solutions.

Assuming an omnipotent, omniscient superintelligence can be a useful exercise, but it should not be used as the basis for all research agendas.

### Instead, improve cost/benefit variables

In science, problems are rarely solved in one fell swoop. Rather than asking, “does this solve every problem?” we should ask “does this make the current situation better?” Instead of trying to build a technical solution and then try to use it to cause a future AGI to swerve towards safety, we should begin steering towards safety now.

The military and information assurance communities, which are used to dealing with highly adversarial environments, do not search for solutions that render all failures an impossibility. Instead, they often take a cost-benefit analysis approach by aiming to increase the cost of the most pressing types of adversarial behavior. Consequently, a cost-benefit approach is a time-tested way to address powerful intelligent adversaries.

Even though no single factor completely guarantees safety, we can drive down risk through a combination of many safety features (defense in depth). Better adversarial robustness, ethical understanding, safety culture, anomaly detection, and so on to collectively make exploitation by adversaries harder, driving up costs.

In practice, the balance between the costs and benefits of adversarial behavior needs to be tilted in favor of the costs. While it would be nice to have the cost of adversarial behavior be infinite, in practice this is likely infeasible. Fortunately, we just need it to be sufficiently large.

In addition to driving up the cost of adversarial behavior, we should of course drive down the cost of safety features (an important high-level contributing factor). This means making safety features useful in more settings, easier to implement, more reliable, less computationally expensive, or have less steep or no tradeoffs with capabilities. Even if an improvement does not completely solve a safety problem once and for all, we should still aim to continue increasing the benefits. In this way, safety becomes something we can continuously improve, rather than an all-or-nothing binary property.

Some note we “only have one chance to get safety right,” so safety is binary. Of course, there are no do-overs if we’re extinct, so whether or not humans are extinct is indeed binary. However, we believe that the probability of extinction due to an event or deployment is not zero or one, but rather a continuous real value that we can reduce by cautiously changing the costs and benefits of hazardous behavior and safety measures, respectively. The goal should be to reduce risk as much as possible over time.

It’s important to note that not all research areas, including those with clear benefits, will have benefits worth their costs. We will discuss one especially important cost to be mindful of: hastening capabilities and the onset of x-risk.

Safety/capabilities tradeoffs

-----------------------------

Safety and capabilities are linked and can be difficult to disentangle. A more capable system might be more able to understand what humans believe is harmful; it might also have more ability to cause harm. Intelligence cuts both ways. We do understand, however, that desirable behavior *can* be decoupled from intelligence. For example, it is well-known that *moral virtues* are distinct from *intellectual virtues*. An agent that is knowledgeable, inquisitive, quick-witted, and rigorous is not necessarily honest, just, power-averse, or kind.

In this section, by *capabilities* we mean *general capabilities.*These include general prediction, classification, state estimation, efficiency, scalability, generation, data compression, executing clear instructions, helpfulness, informativeness, reasoning, planning, researching, optimization, (self-)supervised learning, sequential decision making, recursive self-improvement, open-ended goals, models accessing the Internet, or similar capabilities. We are not speaking of more specialized capabilities for downstream applications (for instance, climate modeling).

It is not wise to decrease some risks (e.g. improving a safety metric) by increasing other risks through advancing capabilities. In some cases, optimizing safety metrics might increase capabilities even if they aren’t being aimed for, so there needs to be a more principled way to analyze risk. We must ensure that growing the safety field does not simply hasten the arrival of superintelligence.

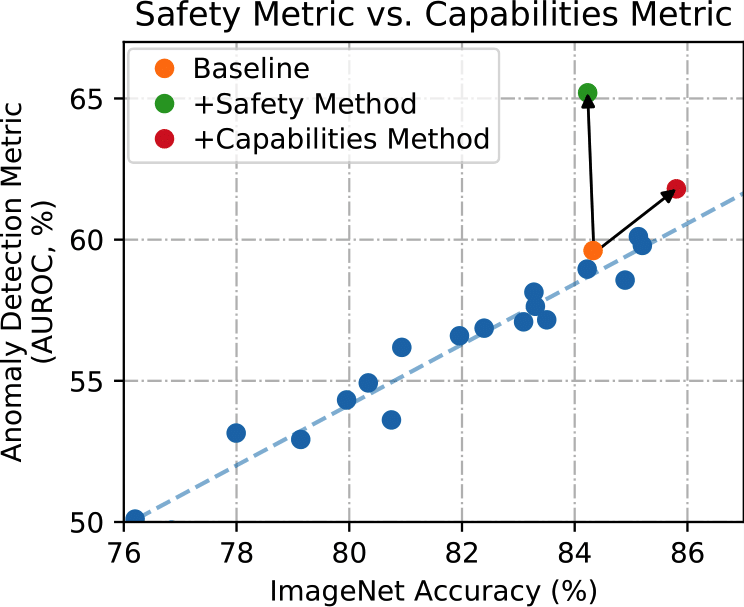

The figure above shows the performance of various methods on standard ImageNet as well as their anomaly detection performance. The overall trendline shows that anomaly detection performance tends to improve along with more general ImageNet performance, suggesting that one way to make “safety progress” is simply to move along the trendline (see the red dot). However, if we want to make [differentialprogress](https://www.nickbostrom.com/existential/risks.html) towards safety specifically, we should instead focus on safety methods that do not simply move along the existing trend (see the green dot). In addition, the trendline also suggests that differential safety progress is in fact *necessary* to attain maximal anomaly detection performance, since even 100% accuracy would only lead to ~88% AUROC. Consequently researchers will need to shift the line up, not just move along the trendline. This isn’t the whole picture. There may be other relevant axes, such as the ease of a method’s implementation, its computational cost, its extensibility, and its data requirements. However, the leading question should be to ask what the effect of a safety intervention is on general capabilities.

It’s worth noting that safety is commercially valuable: systems viewed as safe are more likely to be deployed. As a result, even improving safety without improving capabilities could hasten the onset of x-risks. However, this is a very small effect compared with the effect of directly working on capabilities. In addition, hypersensitivity to any onset of x-risk proves too much. One could claim that any discussion of x-risk at all draws more attention to AI, which could hasten AI investment and the onset of x-risks. While this may be true, it is not a good reason to give up on safety or keep it known to only a select few. We should be precautious but not self-defeating.

### Examples of capabilities goals with safety externalities

[Self-supervised learning](https://arxiv.org/abs/1906.12340) and [pretraining](https://arxiv.org/abs/2004.06100) have been shown to improve various uncertainty and robustness metrics. However, the techniques were developed primarily for the purpose of advancing general capabilities. This shows that it is not necessary to be aiming for safety to improve it, and certain upstream capabilities improvements can simply improve safety “accidentally.”

Improving world understanding helps models better anticipate consequences of their actions. It thus makes it less likely that they will produce unforeseen consequences or take irreversible actions. However, it also increases their power to influence the world, potentially increasing their ability to produce undesirable consequences.

Note that in some cases, even if research is done with a safety goal, it might be indistinguishable from research done with a capabilities goal if it simply moves along the existing trendlines.

### Examples of safety goals with capabilities externalities

Encouraging models to be truthful, when defined as not asserting a lie, may be desired to ensure that models do not willfully mislead their users. However, this may increase capabilities, since it encourages models to have better understanding of the world. In fact, maximally truth-seeking models would be more than fact-checking bots; they would be general research bots, which would likely be used for capabilities research. Truthfulness roughly combines three different goals: accuracy (having correct beliefs about the world), calibration (reporting beliefs with appropriate confidence levels), and honesty (reporting beliefs as they are internally represented). Calibration and honesty are safety goals, while accuracy is clearly a capability goal. This example demonstrates that in some cases, less pure safety goals such as truth can be decomposed into goals that are more safety-relevant and those that are more capabilities-relevant.

One safety goal could be to incentivize collaboration, rather than competition, between different AI systems. This might be useful in reducing high-stakes conflicts that could lead to catastrophic outcomes. However, depending on how it is researched, it may come with capabilities externalities. For instance, focusing on getting agents to perform better in positive-sum games might have a significant effect on general planning ability, which could have further downstream effects.

Better modeling “human preferences” may also be an example of a safety goal with capabilities externalities; we will cover this below.

### Practical steps

When attempting to measure progress towards safety, it’s essential to also measure a method’s contribution to capabilities. One should ask whether a method creates a differential improvement in safety. Rather than relying on intuition to ascertain this, it is necessary to make empirical measurements. Empirical research claiming to differentially improve safety should demonstrate a differential safety improvement empirically. Of course, *reducing*capabilities is not likely to be helpful in practice, as this could make the method less likely to be used in the real-world.

Sometimes it is claimed that more general capabilities are needed to produce safety work, and so working on general capabilities advancements will at some point eventually allow working on safety. We agree that it is not necessarily the case that it could *never* be worth making capabilities advancements in exchange for differential improvements in safety. If at some point in the future it is impossible to make safety progress without an increase in capabilities, there may be more reason to accept capabilities externalities.

However, working on general capabilities for years to start studying a particular safety problem is neither precautious nor necessary. There are fortunately many safety research areas where it’s possible to make contributions without contributing to general capabilities at all. For instance, almost every paper in adversarial robustness hasn’t improved accuracy, because the two are not positively correlated. Similarly, out-of-distribution detection usually doesn’t come with capability externalities, and often focuses on eliciting out-of-distribution detection information from fixed models rather than improving their representations. We will discuss these and other areas and describe their relation to general capabilities in the next post.

An Application: Machine Ethics vs. Learning Task Preferences

------------------------------------------------------------

Preference learning is typically operationalized as learning human preferences over different ways to accomplish a task. This is intended to ensure that agents understand what humans mean, rather than simply what they say. However, modeling “human values” or “human preferences” is often just modeling “user comparisons” or “task preferences,” not unlike the preference or comparison annotations that companies have been collecting for ML-driven translation, advertisement, and search algorithms throughout the past years. First, humans prefer smarter models. This is especially true when humans rate the usefulness of models. As such, modeling task preferences often does not pass the capability externalities test because it includes information about preferences for task-specific behavior (e.g. the quality of a summary). Second, preferences can be inconsistent, ill-conceived, and highly situation-dependent, so they may not be generalizable to the unfamiliar world that will likely arise after the advent of highly-capable models.

Consequently, we recommend trying to make models act in keeping with human values, not model preferences for a broad suite of general tasks. One area trying to do this is [machine ethics](https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ethics-ai/#MachEthi), which is about building ethical AIs. (This is in contrast to AI ethics, which is about “ethics of AI” and is dominated by discussions of fairness, bias, and inequality; by way of its constituent’s Foucualtian presuppositions, it often implicitly [adopts anti-normative positions](https://perso.uclouvain.be/mylene.botbol/Recherche/GenreBioethique/Nussbaum_NRO.htm).) Rather than model task preferences, a core aim of machine ethics is modeling actual human values.

Compared with task preferences, ethical theories and human values such as intrinsic goods may be more generalizable, interpretable, and neglected. They are also more important to us (compared to preferences for high-quality summarization, for instance), and are also plausibly timeless. In addition, many normative factors are common to a number of ethical theories, even if theories disagree about how to combine them. Coarsely, normative factors are intrinsic goods, general constraints, special obligations, and options. An expansion of this list could be wellbeing, knowledge, the exercise of reason, autonomy, friendship, equality, culpability, impartiality, desert, deontological thresholds, intending harm, lying, promises, special obligations, conventions, duties to oneself, options, and so on. Note that these include factors that cover fairness, but also a whole spectrum of additional important factors.

In general, research into the application of ethical theories and the approximation of normative factors appears far less likely to lead to capabilities externalities, because the scope of what is being learned is restricted dramatically. Ethical theories contain less information that is relevant to understanding how to perform general tasks than generic human annotations and comparisons. Still, it’s important to anticipate potential capabilities externalities: for example, one should not try to model consequentialist ethics by building better general predictive world models, as this is likely to create capabilities externalities.

One possible goal of machine ethics is work towards a [moral parliament](https://www.fhi.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Parliamentary-Approach-to-Moral-Uncertainty.pdf), a framework for making ethical decisions under moral and empirical uncertainty. Agents could submit their decisions to the internal moral parliament, which would incorporate the ethical beliefs of multiple stakeholders in informing decisions about which actions should be taken. Using a moral parliament could reduce the probability that we are leaving out important normative factors by focusing on only one moral theory, and the inherent multifaceted, redundant, ensembling nature of a moral parliament would also contribute to making the model less gameable. If a component of the moral parliament is uncertain about a judgment, it could request help from human stakeholders. The moral parliament might also be able to act more quickly to restrain rogue agents than a human could and act in the fast-moving world that is likely to be induced by more capable AI. We don’t believe the moral parliament would solve all problems, and more philosophical and technical work will be needed to make it work, but it is a useful goal for the next few years.

Sometimes it is assumed that a sufficiently intelligent system will simply understand ethics, so there is no need to work on machine ethics. This analysis succumbs to the problems with asymptotic reasoning and assuming omniscience detailed above. In particular, we should not assume that an ethics model can automatically withstand the optimization pressure of another superintelligence, or that it will generalize in the same way as humans under distributional shift. We need to ensure that we will have aligned, reliable, and robust ethical understanding. A proactive ethics strategy is far more likely to succeed than one that naively hopes that the problem can be ignored or taken care of at the last moment. Additionally, on the sociotechnical front, people need time-tested examples if they are to be adopted or required in regulation. A moral parliament will take years to engineer and accrue buy-in, so we cannot trust that our values will be best furthered by a last-minute few-shot moral parliament.

Conclusion

----------

Starting research with asymptotic reasoning, while it has the benefit of aiming for research that has immediately graspable AI x-risk relevance, carries the cost of making research less specific and less tractable. It also reduces the number of research feedback loops.

By focusing on microcosms, empirical research is relevant for reducing AI x-risk, but its relevance is less immediately graspable. However, the reduction in immediately graspable relevance is more than made up for by increased tractability, specificity, measurability, and the information gained from faster feedback loops. Despite these strengths, naive empirical research threatens to produce capabilities externalities, which should be avoided as much as possible.

We propose a strategy to produce tractable tail impacts with minimal capabilities externalities. In summary:

* Pursue tail impacts, reduce moments of peril, start working on safety early, and improve the scaling laws of safety in comparison to capabilities.

* Since impact is likely to be tail distributed, it’s important to understand where tail outcomes emerge from: multiplicative processes, preferential attachment, and the edge of chaos.

* “How can this safety mechanism make strong AI completely safe?” excludes many useful risk reduction strategies. Works that stand up the question “how can this work steer the AI development process in a safer direction?” are also useful for AI x-risk reduction.

* It’s useful to view safety as a continuously improvable property rather than an all-or-nothing binary property.

* We take a stand against capabilities externalities in some safety research directions. AI safety research should be safe.

* Machine ethics should be preferred to learning task preferences, because the latter can have significant capability externalities, and ethics contains more time-tested and reliable values than task-specific preferences do.

* We suggest trying to achieve safety through evolution, rather than only trying to arrive at safety through intelligent design.

|

2994e711-e9c8-4b9b-bd42-93884bb7a635

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

The Potential Impossibility of Subjective Death

Epistemic Status: ~70% confidence, hoping to get some feedback.

I'm going to argue that if we accept three controversial (but not outlandish) assumptions to be true, then subjective death (the cessation of conscious experiences identifying themselves as "you") is impossible. I will keep this post as concise as possible.

----------------------------------------

Here are the three assumptions:

1. We live in a multiverse (e.g. the MWI or Tegmark's MUH is true).

2. Consciousness can be simulated computationally.

3. Identity is "transmitted" through similarity of observer-moments.

Given assumption 1, somewhere "out there" (e.g. in a different Everett branch), there will be worlds that contain "revival simulations" of you (simulations of you being revived and regaining consciousness after your death).

Given assumption 2, these simulations will be conscious and have subjective experience.

Given assumption 3, these revival simulations of you are technically "you" since "you" of this instant is a particular observer-moment that is being computed in a multitude of quantum branches or universes. Your identity is transmitted through the continuity of similar observer-moments since these simulations possess the same memories as you before you died (and hence connect with your last observer moment).

Similar to how the quantum immortality argument says that even though your "reality measure" is reduced after an experiment, you are guaranteed to survive from your perspective because you cannot subjectively experience the branches where you die. Here the argument is that when you die, there will be quantum branches or other universes computing observer-moments of "you" experiencing a revival. Hence you should always expect to be revived after death.

----------------------------------------

These conclusions sound pretty crazy to me intuitively, but if one accepts the assumptions (whether or not those assumptions are true is outside the scope of this post), these conc

|

b1d99f19-e4ef-4a70-a617-fa898c5b3bc0

|

StampyAI/alignment-research-dataset/lesswrong

|

LessWrong

|

Applying utility functions to humans considered harmful

There's a lot of discussion on this site that seems to be assuming (implicitly or explicitly) that it's meaningful to talk about the utility functions of individual humans. I would like to question this assumption.

To clarify: I don't question that you couldn't, *in principle*, modela human's preferences by building this insanely complex utility function. But there's an infinite amount of methods by which you could model a human's preferences. The question is which model is the most useful, and which models have the least underlying assumptions that will lead your intuitions astray.