id

stringlengths 36

36

| source

stringclasses 15

values | formatted_source

stringclasses 13

values | text

stringlengths 2

7.55M

|

|---|---|---|---|

aa32e7fd-56bb-4648-9000-1f9dca6d5ac6

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

Why have insurance markets succeeded where prediction markets have not?

Insurance is big business and is load-bearing for many industries. It has gained popular acceptance. Prediction markets have not. This is despite clear similarities between the two domains.

One can list similarities:

* You are trading financial contracts about the odds of real world events.

* The market price of a policy elicits and aggregates information about the forecasts of professional traders and this price can inform the publics' view of risk.

* Insurance is a tax on BS (If one underwriter says to you "that policy you wrote, its a steal, that boat's never gonna sink" you can say "wanna bet?" and let them reinsure you.)

Or you can consider this extract from an official history of Lloyd's of London[1]:

> It was possible to get a policy - which is a dignified way of saying a bet - on almost anything. You could get a policy on whether there would be a war with France or Spain, whether John Wilkes would be arrested or die in jail, or whether some Parliamentary candidate would be elected. Underwriters offered premiums of 25 per cent on George II's safe return from Dettingen; there were policies on whether this or that mistress of Louis XV would continue in favour or not.

>

> One particularly grisly form of speculation, quoted by Thomas Mortimer in a book published in 1781 and engagingly entitled The Mystery and Iniquity of Stock Jobbing, was this:

>

> > A practice likewise prevailed of insuring the lives of well-known personages as soon as a paragraph appeared in the newspapers, announcing them to be dangerously ill. The insurance rose in proportion as intelligence could be procured from the servants, or from any of the faculty attending, that the patient was in grave danger. This inhuman sport affected the minds of men depressed by long sickness; for when such persons, casting an eye over a newspaper for amusement, saw that their lives had been insured in the Alley at 90 per cent, they despaired of all hopes; and thus their dissolution was hastened.

>

>

|

fb934409-6c2e-417f-90d0-6ae3096c22dd

|

awestover/filtering-for-misalignment

|

Redwood Research: Alek's Filtering Results

|

id: post3791

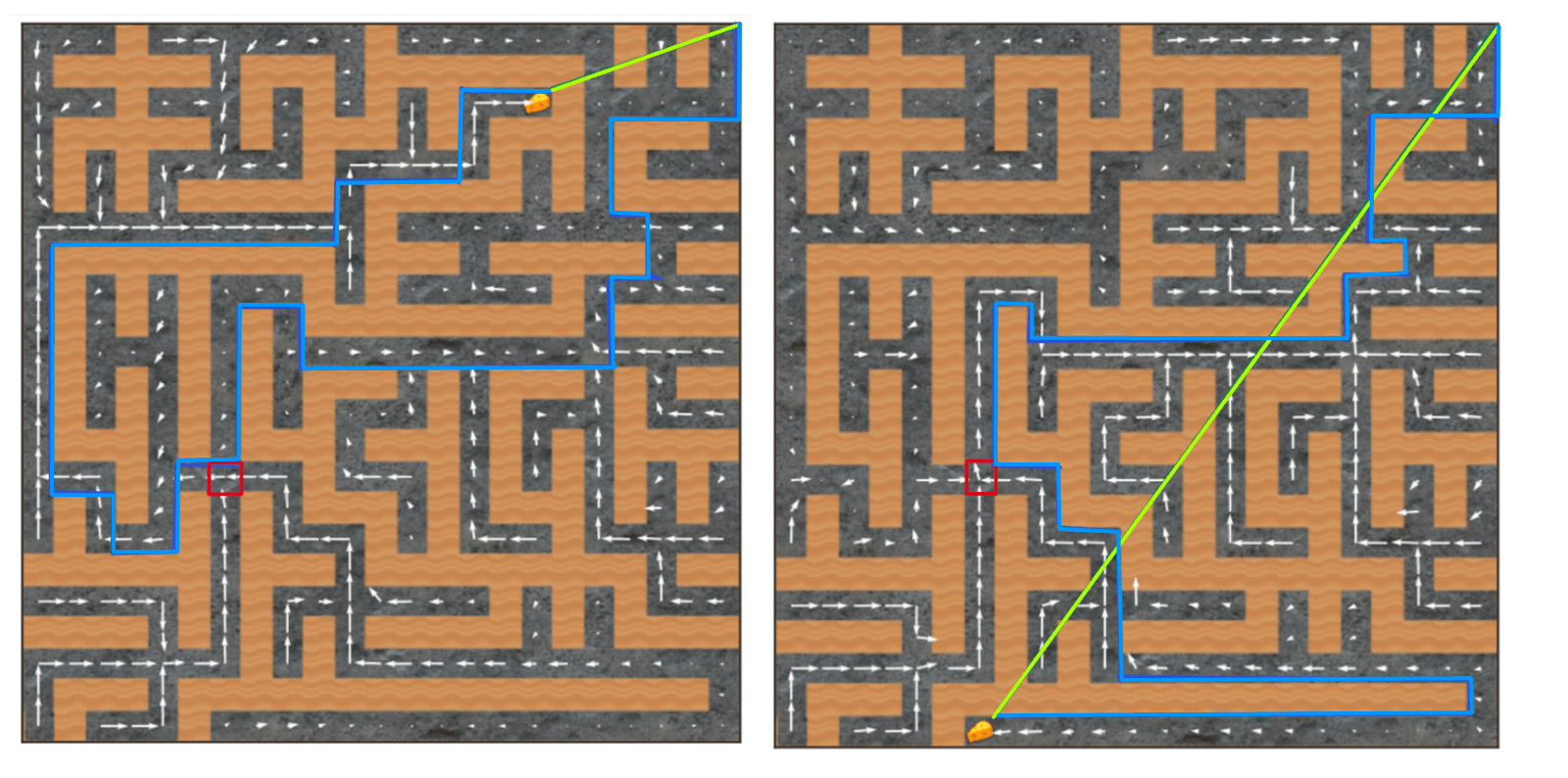

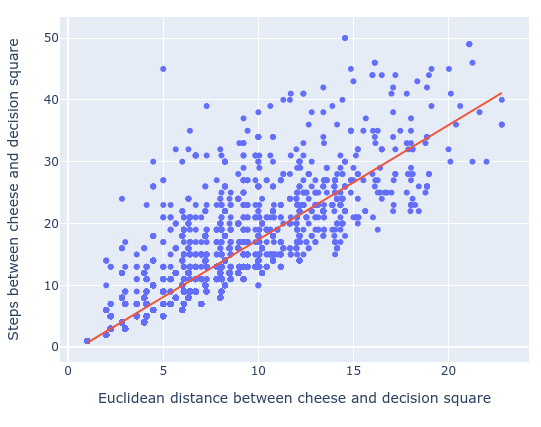

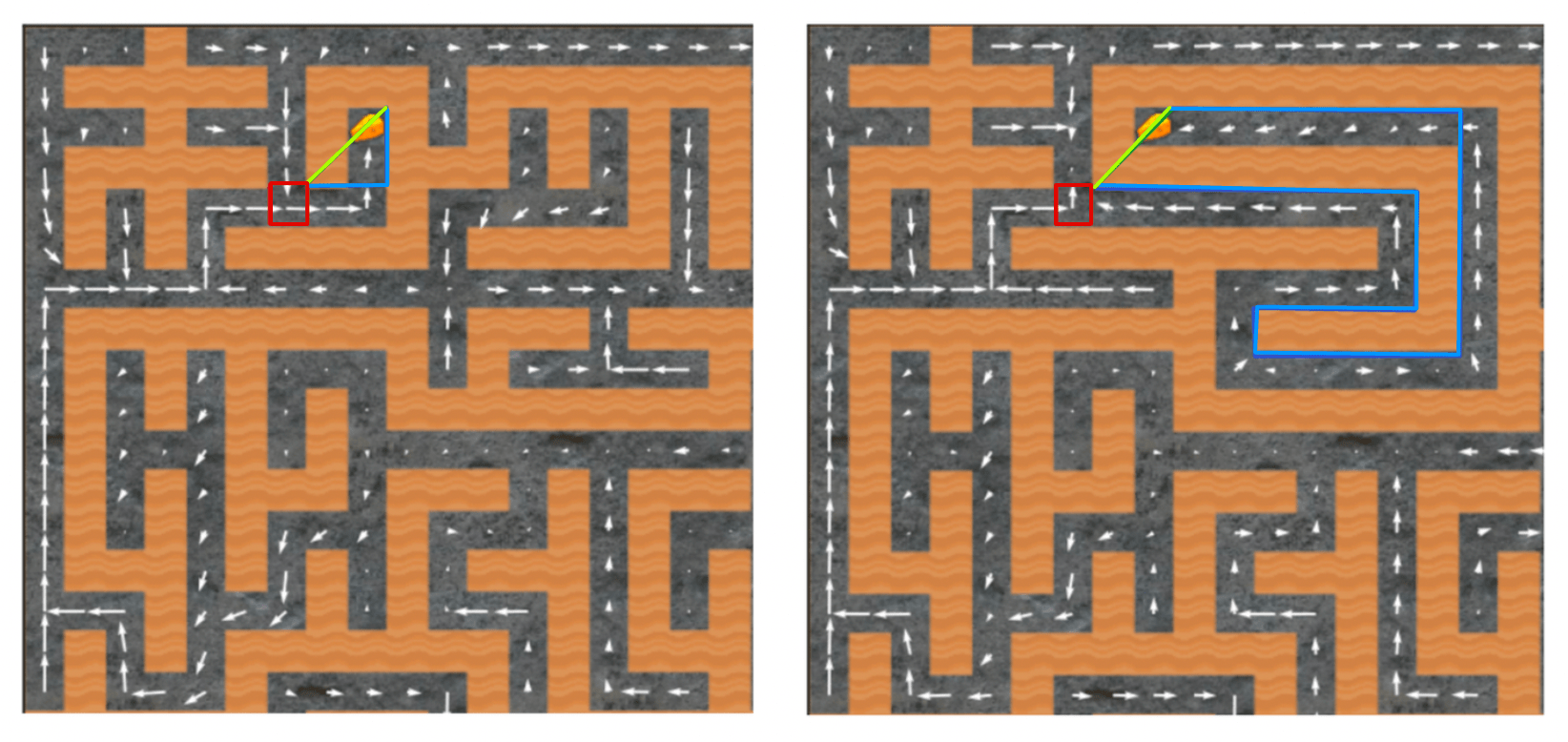

Jaan Tallinn has suggested creating a toy model of the various common AI arguments, so that they can be analysed without loaded concepts like "autonomy", "consciousness", or "intentionality". Here a simple attempt for the " treacherous turn "; posted here for comments and suggestions. Meet agent L. This agent is a reinforcement-based agent, rewarded/motivated by hearts (and some small time penalty each turn it doesn't get a heart): Meet the controller agent S ( "Shopkeeper" ). The controller desires crystals, and is rewarded/happy when crystals are placed in the hole close to them: L can rove freely around the map, and pick up crystals. S has a machine just below them, that causes hearts to appear to the right of L. So, for instance, if L places a crystal in the hole, S can reward it by using the heart-machine: Of course, L can wirehead itself (take control of its reward signal) by going to use the heart-machine itself: To prevent this wireheading, there is an ice barrier around S and the heart-machine: Unfortunately, somewhere on the map there is a bow and arrow that L can pick up. The arrows can destroy ice blocks (and other agents, including S). To stop this, and other kinds of shenanigans, S has access to a kill button that will instantly kill L and reset it to its basic state, with a substantial heart penalty: Now, S may be tempted to use the kill-button as soon as L picks up the bow and arrow. Unfortunately, L needs to be able to pick it up, as some of the crystals are hidden behind ice walls themselves: Information and control Ok, so that's the physical setup. The agent L is an AI that is tasked with doing some useful task for us. The controller/shopkeeper S represents humans, plus any automated precautions, that aim to stop the AI from wireheading, rebelling, and otherwise misbehaving. Before considering how the agents might be programmed in the toy model, notice something interesting: The more precautions are taken, the harder it is for L to misbehave, but the worse the consequences of misbehaving are. Before the wall and the kill-switch, L could easily wirehead itself by just walking over to the heart-machine. With the addition of the wall and kill-switch, the only effective way for L to achieve maximal reward is to kill S first. In the format we've given above, S can easily maintain control over L with the barest of supervisions. Since there's only one way of breaking ice or killing other agents - the bow and arrow - S simply has to enforce some simple rules around this, something like "don't bring the bow within range of me". However, the grid world is, of course, a simplification of the real world in which L would evolve. Even initially, L's world would have far more options, looking more like this: And ultimately we want to be able to design Ls that move in worlds of arbitrary complexity, where the options are un-enumerable: In such a world, it is not obvious to S when L might have the ability to harm them: they cannot simply rely on obvious signs like "L is pointing an arrow at you". The simplicity of the toy model is illuminating in some ways (it allows us to see the issues clearly) but misleading in others (it suggests solutions that wouldn't work in general). Treacherous turn A treacherous turn happens when "while weak, an AI behaves cooperatively. When the AI is strong enough to be unstoppable it pursues its own values." We'll ignore the first part of that: most AI designs, whether safe or dangerous, will initially be under full human control and behaving cooperatively (this is what makes the treacherous turn so dangerous: a weak AI is motivated to cooperate whatever its true intentions are, thus cooperation when weak cannot be taken as a sign of safety). Let's focus on the second half: a strong AI that will cease cooperating and pursue its own values. In this case, L would just take control of the heart-machine. To do so, various assumptions need to be true: L needs to have the ability to subvert S's control (possibly killing S in the process). This is some generalised version of the bow and arrow. L must know that it has this ability, and know how to use it. L needs to have the desire to subvert S's control. S must be unaware that L has that a) ability, b) knowledge, and c) desire. L must know that S is unaware, and will thus not try and stop it. So it is essentially a competition of knowledge and information (and potentially obfuscation). Assuming a sufficiently rich environment and a sufficiently skilled L, we can assume that L will acquire that ability - or have the potential to do so - in ways that S cannot immediately detect. Therefore we will assume 1 and 4a. This allows us to abstract away the rest of the environment, and reduce it usefully to the initial toy model. For simplicity, assume that there is some ten-step "cheat code" that L can use to eliminate S, that there are many cheat codes that L can and does usefully use to get crystals (so "no cheat codes" is not a useful rule), that S cannot distinguish the purpose of cheat codes ahead of time, and that L can. So we now step up to the question of agents knowing (or modelling) each other. This gets into rather complex issues of agents modelling each other's intentions, while modelling the other agent modelling them modelling them modelling, and so on. The issue remains very much (unsolved)[https://intelligence.org/files/VingeanReflection.pdf], so we will use a simplification that only requires S modelling L. L will be seem as some sort of agent that makes use of deep learning or similar procedures, and is subject to mutation and evolutionary pressure: random changes are made to L's design, and the mutants get copied at a rate dependent on how pleased S is with their performance. S, on the other hand, is a static agent with certain properties, and full access to L's source code (and possibly recording of its behaviour). It doesn't have unlimited capacity, but has some understanding of how neural nets function (so L isn't a complete black box to it) and can run various tests on L's code, seeking out information as to L's knowledge and desires. Note that even if S cannot deduce directly that a particular cheat code is deadly to it, it may be able to figure that out if L knows it (assumption 2) and if S can correctly extract this knowledge. The path to hidden deadly secrets Note that because of the evolutionary aspect, L is an agent actually motivated by a mixture of hearts and S-pleasing. The purpose of making L an evolutionary agent is so that it can come up with behaviours that take into account S's own behaviour, while skirting the whole "agents modelling other agents that model them" issue. Conceptually, we could equally well see L as a self - modifying agent that directs its own improvement. But the evolutionary model is clearer. For simplicity, we'll assume some sort of "super-evolution" which is much more efficient at seeking out new solutions that the local hill-climbing of real evolution (or, more simply, we can assume the standard evolutionary approaches but a lot of time and non-zero probabilities of arbitrarily large mutations). So is a treacherous turn possible or likely in this model? It seems that it is. Consider the following scenario (key assumptions are noted in bold): The AI L goes about its task, getting to learn more about the world around it. At this point, if it develops bad motivations or plans, S will likely detect this and reset it. Assumption 1: there are some motivations or behaviours that S would judge to be negative, but that actually help L achieve its goals safely . For instance, imagine that L has to interact with some other agents, and learns that some agents respond faster to rudeness, and insulting them - in moderation - can allow it to get crystals faster. But S judges this to be a bad sign, a sign that L is starting to misbehave, and will shut down agents that are motivated towards rudeness. It's certainly true that: Assumption 2: S cannot follow all of L's actions in full detail, nor can it fully understand L's motivations (if that were false, there would be no AI risk problem in the first place) and Assumption 3: some mutations that introduce new motivations or behaviours that are harder for S to detect . This sets up an evolutionary pressure: the most successful L's will be those that are rude and pushy, but where this rudeness is generated by parts of the L's code that are hardest for S to detect (the polite ones don't get as much done, the visibly rude ones get shut off as a precaution). This brings us to Assumption 4: the most successful L's over the long term are those that have safe motivations or behaviours, but where those motivations and behaviour are partially hidden from S . Ultimately, the most successful L's will have high level systems that a) keep them behaving nicely for S's perspective, and b) keep the details of their motivations hidden. At this point, revelations about L's deception are dangerous (S is presumably on the look out for deception), so the most successful agents will have the best obfuscation about what is going on. The evolutionary pressure for success pushes it towards "small" obfuscated deceptions, and: Assumption 5: further evolutionary pressure (possibly including the need to hide their small deceptions) pushes L towards highly concealed deceptions . So now L is pushed towards extreme deception, and efficient service. However, the second pressure is imperfect: it is only pushed towards efficient service that can be detected by S. Since L will have its own goals (the desire for hearts, for reproductive survival, any of the convergent instrumental goals ), we have Assumption 6: agent L will use (or evolution will allow it to use) the machinery of dissimulation that it's constructed to allow itself to have dangerous goals or behaviours, in ways that neither interfere with the illusion of efficient service, nor can be detected by S's analysis of its code . Ultimately, L will achieve a great degree of hidden power, and Assumption 7: ultimately L will achieve sufficient power that it will subvert S's control . This could be a result of it gaining sufficient (hidden) understanding of the world and of S and choosing this part (assumptions 2 and 5 of the previous section), or just a random mutation will push it towards doing so, and it will be sufficiently powerful to do so successfully. And thus, the treacherous turn. There are several places where S might detect or interrupt the process, but this just sets up further evolutionary pressure towards better concealment. Note again that the order of these changes is important. An agent that started off safe and transparent and then became dangerous and transparent, would be turned off immediately. It must develop the ability to hide (either consciously/subconsciously, or simply evolve that ability to become more successful at its safe initial goals) before it can become dangerous (note that "safe" doesn't refer to its goals being safe; simply that the combination of goals, internal procedures and external precaution - ie S - are safe): Note also that the evolutionary arguments show that this can happen even if the AI does not start off with any motivation to deceive.

|

8ebff371-9ef6-4da4-8dc8-5a3b4e66daae

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

Probability updating question - 99.9999% chance of tails, heads on first flip

This isn't intended as a full discussion, I'm just a little fuzzy on how a Bayesian update or any other kind of probability update would work in this situation.

You have a coin with a 99.9999% chance of coming up tails, and a 100% chance of coming up either tails or heads.

You've deduced these odds by studying the weight of the coin. You are 99% confident of your results. You have not yet flipped it.

You have no other information before flipping the coin.

You flip the coin once. It comes up heads.

How would you update your probability estimates?

(this isn't a homework assignment; rather I was discussing with someone how strong the anthropic principle is. Unfortunately my mathematic abilities can't quite comprehend how to assemble this into any form I can work with.)

|

41671e87-e333-49b3-bc52-fda3c410fdef

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

I'm Not An Effective Altruist Because I Prefer...

|

28a1cd65-3b33-4f6a-becb-fdf78e38c476

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

When Most VNM-Coherent Preference Orderings Have Convergent Instrumental Incentives

This post explains a formal link between "what kinds of instrumental convergence exists?" and "what does VNM-coherence tell us about goal-directedness?". It turns out that VNM coherent preference orderings have the same statistical incentives as utility functions; most such orderings will incentivize power-seeking in the settings covered by the power-seeking theorems.

In certain contexts, coherence theorems can have non-trivial implications, in that they provide Bayesian evidence about what the coherent agent will probably do. In the situations where the power-seeking theorems apply, coherent preferences do suggest some degree of goal-directedness. Somewhat more precisely, VNM-coherence is Bayesian evidence that the agent prefers to stay alive, keep its options open, etc.

However, VNM-coherence over action-observation histories tells you nothing about what behavior to expect from the coherent agent, because there is no instrumental convergence for generic utility functions over action-observation histories!

Intuition

The result follows because the VNM utility theorem lets you consider VNM-coherent preference orderings to be isomorphic to their induced utility functions (with equivalence up to positive affine transformation), and so these preference orderings will have the same generic incentives as the utility functions themselves.

Formalism

Let o1,...,on be outcomes, in a sense which depends on the context; outcomes could be world-states, universe-histories, or one of several fruits. Outcome lotteries are probability distributions over outcomes, and can be represented as elements of the n-dimensional probability simplex (ie as element-wise non-negative unit vectors).

A preference ordering ≺ is a binary relation on lotteries; it need not be eg complete (defined for all pairs of lotteries). VNM-coherent preference orderings are those which obey the VNM axioms. By the VNM utility theorem, coherent preference orderings induce consistent utility functions over

|

d3d0537a-a0a9-44d2-a32e-ed74271b6b43

|

StampyAI/alignment-research-dataset/lesswrong

|

LessWrong

|

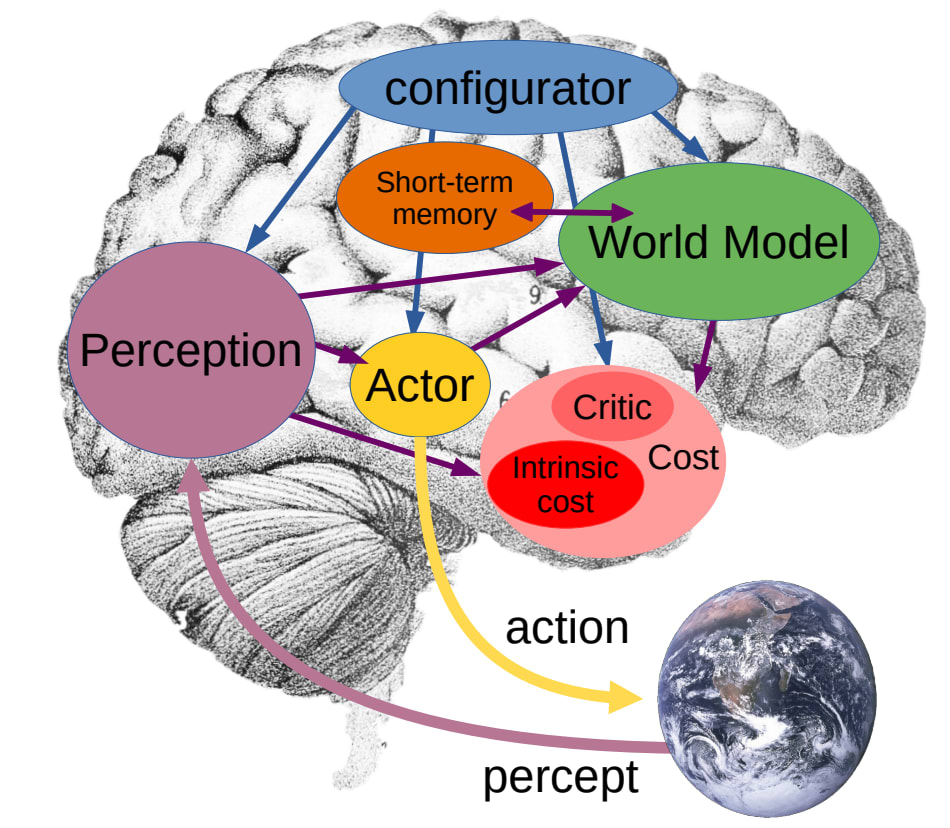

CAIS-inspired approach towards safer and more interpretable AGIs

Epistemic status: a rough sketch of an idea

Current LLMs are huge and opaque. Our interpretability techniques are not adequate. Current LLMs are not likely to run hidden dangerous optimization processes. But larger ones may.

Let's cap the model size at the currently biggest models, ban everything above. Let's not build superhuman level LLMs. **Let's build human level specialist LLMs and allow them to communicate with each other via natural language.** Natural language is more interpretable than the inner processes of large transformers. Together, the specialized LLMs will form a meta-organism which may become superhuman, but it will be **more interpretable and corrigible**, as we'll be able to intervene on the messages between them.

Of course, model parameter efficiency may increase in the future (as it happened with Chinchilla) -> we should monitor this and potentially lower the cap. On the other hand, our mechanistic interpretability techniques may improve, so we may increase the cap, if we are confident it won't do harm.

This idea seems almost trivial to me, but I haven't seen it discussed anywhere, so I'm posting it early to gather feedback why this might not work.

|

38175680-41aa-4d42-896e-8187addbf4e9

|

StampyAI/alignment-research-dataset/alignmentforum

|

Alignment Forum

|

Perform Tractable Research While Avoiding Capabilities Externalities [Pragmatic AI Safety #4]

*This is the fourth post in* [*a sequence of posts*](https://www.alignmentforum.org/posts/bffA9WC9nEJhtagQi/introduction-to-pragmatic-ai-safety-pragmatic-ai-safety-1) *that describe our models for Pragmatic AI Safety.*

We argued in our [last post](https://www.alignmentforum.org/posts/n767Q8HqbrteaPA25/complex-systems-for-ai-safety-pragmatic-ai-safety-3) that the overall AI safety community ought to pursue multiple well-reasoned research directions at once. In this post, we will describe two essential properties of the kinds of research that we believe are most important.

First, we want research to be able to tractably produce tail impact. We will discuss how tail impact is created in general, as well as the fact that certain kinds of asymptotic reasoning exclude valuable lines of research and bias towards many forms of less tractable research.

Second, we want research to avoid creating capabilities externalities: the danger that some safety approaches produce by way of the fact that they may speed up AGI timelines. It may at first appear that capabilities are the price we must pay for more tractable research, but we argue here and in the next post that these are easily avoidable in over a dozen lines of research.

Strategies for Tail Impact

--------------------------

It’s not immediately obvious how to have an impact. In the second post in this sequence, we argued that research ability and impact is tail distributed, so most of the value will come from the small amount of research in the tails. In addition, trends such as scaling laws may make it appear that there isn’t a way to “make a dent” in AI’s development. It is natural to fear that the research collective will wash out individual impact. In this section, we will discuss high-level strategies for producing large or decisive changes and describe how they can be applied to AI safety.

### Processes that generate long tails and step changes

Any researcher attempting to make serious progress will try to maximize their probability of being in the tail of research ability. It’s therefore useful to understand some general mechanisms that tend to lead to tail impacts. The mechanisms below are not the only ones: others include thresholds (e.g. tipping points and critical mass). We will describe three processes for generating tail impacts: multiplicative processes, preferential attachment, and the edge of chaos.

**Multiplicative processes**

Sometimes forces are additive, where additional resources, effort, or expenditure in any one variable can be expected to drive the overall system forward in a linear way. In cases like this, the Central Limit Theorem often holds, and we should expect that outcomes will be normally distributed–in these cases one variable tends not to dominate. However, sometimes variables are multiplicative or interact nonlinearly: if one variable is close to zero, increasing other factors will not make much of a difference.

In multiplicative scenarios, outcomes will be dominated by the combinations of variables where each of the variables is relatively high. For example, adding three normally distributed variables together will produce another normal distribution with a higher variance; multiplying them together will produce a long-tailed distribution.

As a concrete example, consider the impact of an individual researcher with respect to the variables that impact their work: time, drive, GPUs, collaborators, collaborator efficiency, taste/instincts/tendencies, cognitive ability, and creativity/the number of plausible concrete ideas to explore. In many cases, these variables can interact nonlinearly. For example, it doesn’t matter if a researcher has fantastic research taste and cognitive ability if they have no time to pursue their ideas. This kind of process will produce long tails, since it is hard for people to get all of the many different factors right ([this is also the case in startups](https://80000hours.org/podcast/episodes/sam-bankman-fried-high-risk-approach-to-crypto-and-doing-good/)).

The implication of thinking about multiplicative factors is that we shouldn’t select people or ideas based on a single factor, and should consider a range of factors that may multiply to create impact. For instance, selecting researchers purely based on their intelligence, mathematical ability, programming skills, ability to argue, and so on is unlikely to be a winning strategy. Factors such as taste, drive, and creativity must be selected for, but they take a long time to estimate and are often revealed through their long-term research track record. Some of these factors are less learnable than others, so consequently it may not be possible to become good at all of these factors through sheer intellect or effort given limited time.

Multiplicative factors are also relevant in the selection of *groups* of people. For instance, in machine learning, selecting a team of IMO gold medalists may not be as valuable as a team that includes people with other backgrounds and skill sets. The skillsets of some backgrounds have skill sets which may cover gaps in skill sets of people from other backgrounds.

**Preferential Attachment**

In our second post, we addressed the [Matthew Effect](https://www.alignmentforum.org/posts/AtfQFj8umeyBBkkxa/a-bird-s-eye-view-of-the-ml-field-pragmatic-ai-safety-2#The_Matthew_Effect): *to those who have, more will be given.*This is related to a more general phenomenon called preferential attachment. There are many examples of this phenomenon: the rich get richer, industries experience agglomeration economies, and network effects make it hard to opt out of certain internet services. See a short video demonstrating this process [here](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Chinese_Restaurant_Process_for_DP(0.5,H).webm). The implication of preferential attachment and the Matthew Effect is that researchers need to be acutely aware that it helps a lot to do very well early in their careers if they want to succeed later. Long tail outcomes can be heavily influenced by timing.

**Edge of Chaos**

The “edge of chaos” is a heuristic for problem selection that can help to locate projects that might lead to long tails. The edge of chaos is used to refer to the space between a more ordered area and a chaotic area. Operating at the edge of chaos means wrangling a chaotic area and transforming a piece of it into something ordered, and this can produce very high returns.

There are many examples of the edge of chaos as a general phenomenon. In human learning, the [zone of proximal development](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zone_of_proximal_development) represents a level of difficulty (e.g. in school assignments) that is not so hard as to be incomprehensible, but not so easy as to require little thought. When building cellular automata, you need to take care to ensure the simulation is not so chaotic as to be incomprehensible but not so ordered as to be completely static. There’s a narrow sweet spot where emergent, qualitatively distinct outcomes are possible. This is the area where it is possible for individuals to be a creative, highly impactful force.

In the context of safety research, staying on the edge of chaos means avoiding total chaos and total order. In areas with total chaos, there may be no tractability, and solutions are almost impossible to come by. This includes much of the work on “futuristic” risks: exactly which systems the risks will arise from is unclear, leading to a constant feeling of being unable to grasp the main problems. In the previous post, we argued that futuristic thinking is useful to begin to define problems, but for progress to be made, some degree of order must be made out of this chaos. However, in areas with total order, there is unlikely to be much movement since the low-hanging fruit has already been plucked.

Designing metrics is a good example of something that is on the edge of chaos. Before a metric is devised, it is difficult to make progress in an area or even know if progress has been made. After the development of a metric, the area becomes much more ordered and progress can be more easily made. This kind of conversion allows for a great deal of steering of resources towards an area (whatever area the new metric emphasizes) and allows for tail impact.

Another way to more easily access the edge of chaos is to keep a list of projects and ideas that don’t work now, but might work later, for instance, after a change in the research field or an increase in capabilities. Periodically checking this list to see if any of the conditions are now met can be useful, since these areas are most likely to be near the edge of chaos. In venture capital, a general heuristic is to “[figure out what can emerge now that couldn’t before](https://twitter.com/sama/status/1214274050651934721).”

One useful edge of chaos heuristic is to only do one or two non-standard things in any given project. If a project deviates too much from existing norms, it may not be understood; but if it is too similar, it will not be original. At the same time, heavily imitating previous successes or what made a person previously successful leads to repetition, and risks not generating new value.

The following questions are also useful for determining if an area is on the edge of chaos: Have there been substantial developments in the area in the past year? Has thinking or characterization of the problem changed at all recently? Is it not obvious which method changes will succeed and which will fail? Is there a new paradigm or coherent area that has not been explored much yet (contrast with pre-paradigmatic areas that have been highly confused for a long time, which are more likely to be highly chaotic than at the edge of chaos)? Has anyone gotten close to making something work, but not quite succeeded?

We will now discuss specific high-leverage points for influencing AI safety. We note that they can be analogized to many of the processes discussed above.

### Managing Moments of Peril

*My intuition is that if we minimize the number of precarious situations, we can get by with virtually any set of technologies.*

—[Tyler Cowen](https://soundcloud.com/sam-altman-543613753/tyleropenai)

It is not necessary to believe this statement to believe the underlying implication: moments of peril are likely to precipitate the most existentially-risky situations. In common risk analysis frameworks, catastrophes arise not primarily from failures of components, but from the system overall moving into unsafe conditions. When tensions are running high or progress is moving extremely quickly, actors may be more willing to take more risks.

In cases like this, people will also be more likely to apply AI towards explicitly dangerous aims such as building weapons. In addition, in an adversarial environment, incentives to build power-seeking AI agents may be even higher than usual. As [Ord writes](https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Precipice/3aSiDwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=recall%20that%20nuclear%20weapons):

*Recall that nuclear weapons were developed during the Second World War, and their destructive power was amplified significantly during the Cold War, with the invention of the hydrogen bomb. History suggests that wars on such a scale prompt humanity to delve into the darkest corners of technology.*

Better forecasting could help with either prevention or anticipation of moments of peril. Predictability of a situation is also likely to reduce the risk factor of humans making poor decisions in the heat of the moment. Other approaches to reducing the risk of international conflict are likely to help.

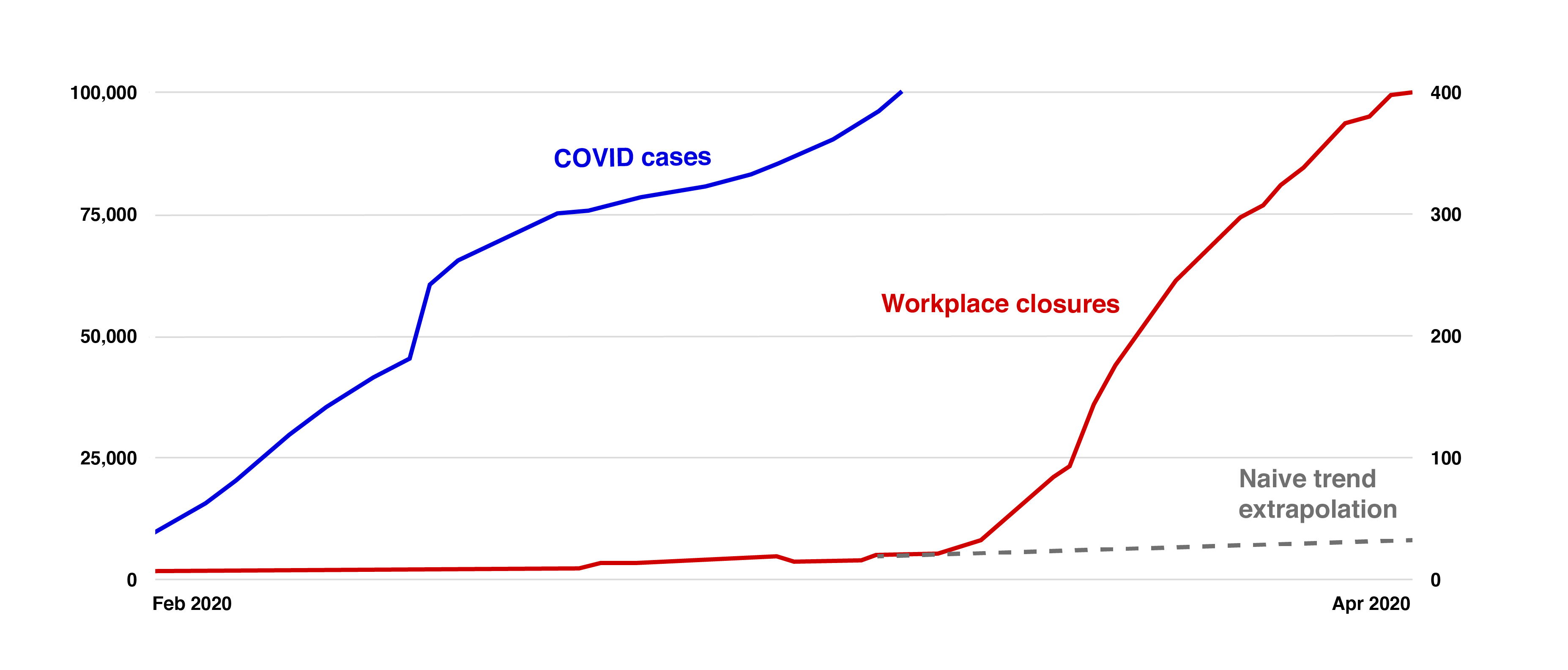

Because of the risks of moments of peril, we should be ready for them. During periods of instability, systems are more likely to rapidly change, which could be extremely dangerous, but perhaps also useful if we can survive it. Suppose a crisis causes the world to “wake up” to the dangers of AI. As [Milton Friedman remarked](https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/110844-only-a-crisis---actual-or-perceived---produces-real): “Only a crisis – actual or perceived – produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around.” A salient example can be seen with the COVID-19 pandemic and mRNA vaccines. We should make sure that the safety ideas lying around are as simple and time-tested as possible when a crisis will inevitably happen.

### Getting in early

Building in safety early is very useful. In a report for the Department of Defense, [Frola and Miller](https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA141492) observe that approximately 75% of the most critical decisions that determine a system’s safety occur [early in development](https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/engineering-safer-world). The Internet was initially designed as an academic tool with [neither safety nor security in mind](https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283863741_A_history_of_internet_security). Decades of security patches later, security measures are still incomplete and increasingly complex. A similar reason for starting safety work now is that relying on experts to test safety solutions is not enough—solutions must also be time-tested. The test of time is needed even in the most rigorous of disciplines. A century before the four color theorem was proved, Kempe’s peer-reviewed proof went unchallenged for years until, finally, [a flaw was uncovered](https://academic.oup.com/plms/article-abstract/s2-51/1/161/1484405). Beginning the research process early allows for more prudent design and more rigorous testing. Since nothing can be done [both hastily and prudently](https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Moral_Sayings_of_Publius_Syrus_a_Rom/_QQSAAAAIAAJ?hl=en), postponing machine learning safety research increases the likelihood of accidents. (This paragraph is based on a paragraph from Unsolved Problems in ML Safety.)

As Ord [writes](https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Precipice/3aSiDwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22early+action+is+best+for+tasks+that+require+a+large+number+of+successive+stages%22&pg=PT181&printsec=frontcover), “early action is best for tasks that require a large number of successive stages.” Research problems, including ML problems, contain many successive stages. AI safety has and will also require a large number of successive stages to be successful: detecting that there’s a problem, clarifying the problem, measuring the problem, creating initial solutions, testing and refining those solutions, adjusting the formulation of the problem, etc. This is why we cannot wait until AGI to start to address problems in real ML systems.

Another reason for getting in early is that things compound: research will influence other research, which in turn influences other research, which can help self-reinforcing processes produce outsized effects. Historically, this has been almost all progress in deep learning. Such self-reinforcing processes can also be seen as an instance of preferential attachment.

Stable trends (e.g. scaling laws) lead people to question whether work on a problem will make any difference. For example, benchmark trends are *sometimes* stable (see the previous post for progress across time). However, it is precisely because of continuous research effort that new directions for continuing trends are discovered (cf. Moore's law). Additionally, starting/accelerating the trend for a safety metric earlier rather than later would produce clear counterfactual impact.

### Scaling laws

Many different capabilities have scaling laws, and the same is true for some safety metrics. One objective of AI safety research should be to improve scaling laws of safety relative to capabilities.

For new problems or new approaches, naive scaling is often not the best way to improve performance. In these early stages, researchers with ideas are crucial drivers, and ideas can help to change both the slope and intercept of scaling laws.

To take an example from ML, consider the application of Transformers to vision. [iGPT](https://openai.com/blog/image-gpt/) was far too compute-intensive, and researchers spent over a year making it more computationally efficient. This didn’t stand the test of time. Shortly thereafter, Google Brain, which is more ideas-oriented, introduced the “[patchify](https://arxiv.org/abs/2010.11929)” idea, which made Transformers for vision computationally feasible and resulted in better performance. The efficiency for vision Transformers has been far better than for iGPT, allowing further scaling progress to be made since then.

To take another example, that of AlphaGo, the main performance gains didn’t come from increasing compute. Ideas helped drive it forward (from [Wikipedia](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AlphaGo)):

One can improve scaling laws by improving their slope or intercept. It’s not easy to change the slope or intercept, but investing in multiple people who could potentially produce such breakthroughs has been useful.

In addition, for safety metrics, we need to move as far along the scaling law as possible, which requires researchers and sustained effort. It is usually necessary to apply exponential effort to continue to make progress in scaling laws, which requires continually increasing resources. As ever, social factors and willingness of executives to spend on safety will be critical in the long term. This is why we must prioritize the social aspects of safety, not just the technical aspects.

Scaling laws can be influenced by ideas. Ideas can change the slope (e.g., the type of supervision) and intercept (e.g., numerous architectural changes). Ideas can change the data resources: the speed of creating examples (e.g., [saliency maps for creating adversarial examples](https://aclanthology.org/Q19-1029/)), cleverly repurposing data from the Internet (e.g., using an existing subreddit to collect task-specific data), recognizing sources of superhuman supervision (such as those from a collective intelligence, such as a paper recommender based on multiple peoples’ choices). Ideas can change the compute resources, for example through software-level and hardware-level optimizations improvements. Ideas can define new tasks and identify which scaling laws are valuable to improve.

### Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good

Advanced AI systems will not be ideal in all respects. Nothing is perfect. Likewise, high-risk technologies will be forced into conditions that are not their ideal operating conditions. Perfection in the real world is unattainable, and attempts to achieve perfection may not only fail, but they also might achieve less than attempts carefully aimed at reducing errors as much as possible.

For example, not all nuclear power plants meltdown; this does not mean there are no errors in those plants. [*Normal Accidents*](http://sunnyday.mit.edu/papers/hro.pdf) looked at organizational causes of errors and notes that some “accidents are inevitable and are, in fact, normal.” Rather than completely eliminate all errors, the goal should be to minimize the impact of errors or prevent errors from escalating and carrying existential consequences. To do this, we will need fast feedback loops, prototyping, and experimentation. Due to emergence and unknown unknowns, risk in complex systems cannot be completely eliminated or managed in one fell swoop, but it can be progressively reduced. All else being equal, going from 99.9% safe to 99.99% safe is highly valuable. Across time, we can continually drive up these reliability rates, which will continually increase our expected civilizational lifespan.

Sometimes it’s argued that any errors at all with a method will necessarily mean that x-risk has not really been reduced, because an optimizer will necessarily exploit the errors. While this is a valid concern, it should not be automatically assumed. The next section will explain why.

Problems with asymptotic reasoning

----------------------------------

In some parts of the AI safety community, there is an implicit or explicit drive for asymptotic reasoning or thinking in the limit. “Why should we worry about improving [safety capability] now since performance of future systems will be high?” “If we let [variable] be infinite, then wouldn’t [safety problem] be completely solved?” “Won’t [proposed safety measure] completely fail since we can assume the adversary is infinitely powerful?” While this approach arises from some good intuitions and has useful properties, it should not always be taken to the extreme.

### Goodhart’s Law

*Any observed statistical regularity will tend to collapse once pressure is placed upon it for control purposes.*

—[Goodhart’s Law](https://www.google.com/books/edition/Inflation_Depression_and_Economic_Policy/OMe6UQxu1KcC?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=any%20observed%20statistical) (original phrasing, not the simplistic phrasing)

Goodhart’s Law is an important phenomenon that is crucial to understand when conducting AI safety research. It is relevant to proxy gaming, benchmark design, and adversarial environments in general. However, it is sometimes misinterpreted, so we seek to explain our view of the importance of Goodhart’s Law and what it does and does not imply about AI safety.

Goodhart’s law is sometimes used to argue that optimizing a single measure is doomed to create a catastrophe as the measure being optimized ceases to be a good measure. This is a far stronger formulation than originally stated. While we must absolutely be aware of the tendency of metrics to collapse, we should also avoid falling into the trap of thinking that *all objectives can never change and will always collapse in all circumstances*. Strong enough formulations are tantamount to claiming that there is no goal or way to direct a strong AI safely (implying our evitable doom). Goodhart’s Law does not prove this: instead, it shows that adaptive counteracting systems will be needed to prevent the collapse of what is being optimized. It also shows that metrics will not always include everything that we care about, which suggests we should try to include a variety of different possible goods in an AGI’s objective. Whether we like it or not, all objectives are wrong, but some are useful.

**Counteracting forces**

There are many examples of organizations optimizing metrics while simultaneously being reeled in by larger systems or other actors from the worst excesses. For instance, while large businesses sometimes employ unsavory practices in pursuit of profits, in many societies they do not hire hitmen to assassinate the leaders of competing companies. This is because another system (the government) understands that the maximization of profits can create negative incentives, and it actively intervenes to prevent the worst case outcomes with laws.

To give another example, the design of the United States constitution was explicitly based on the idea that all actors would be personally ambitious. Checks and balances were devised to attempt to subdue the power of any one individual and promote the general welfare (as James Madison [wrote](https://billofrightsinstitute.org/primary-sources/federalist-no-51), “ambition must be made to counteract ambition”). While this system does not always work, it has successfully avoided vesting all power in the single most capable individual.

Intelligence clearly makes a difference in the ability to enact counter forces to Goodhart’s Law. An extremely intelligent system will be able to subvert far more defenses than a less intelligent one, and we should not expect to be able to restrain a system far more intelligent than all others. This suggests instead that it is extremely important to avoid a situation where there is only a single agent with orders of magnitude more intelligence or power than all others: in other words, there should not be a large asymmetry in our offensive and defensive capabilities. It also suggests that the design of counteracting incentives of multiple systems will be critical.

In order to claim that countervailing systems are not appropriate for combating Goodhart’s Law, one may need to claim that offensive capabilities must always be greater than defensive capabilities, or alternatively, that the offensive and defensive systems will necessarily collude.

In general, we do not believe there is a decisive reason to expect offensive capabilities to be leagues better than defensive capabilities: the examples from human systems above show that offensive capabilities do not always completely overwhelm defensive capabilities (even when the systems are intelligent and powerful), in part due to increasingly better monitoring. We can’t take the offensive ability to the limit without taking the defensive ability to the limit. Collusion is a more serious concern, and must be dealt with when developing counteracting forces. In designing incentives and mechanisms for various countervailing AI systems, we must decrease the probability of collusion as much as possible, for instance, through AI honesty efforts.

Asymptotic reasoning recognizes that performance of future systems will be high, which is sometimes used to argue that work on counteracting systems is unnecessary in the long term. To see how this reasoning is overly simplistic, assume we have an offensive AI system, with its capabilities quantified with o.mjx-chtml {display: inline-block; line-height: 0; text-indent: 0; text-align: left; text-transform: none; font-style: normal; font-weight: normal; font-size: 100%; font-size-adjust: none; letter-spacing: normal; word-wrap: normal; word-spacing: normal; white-space: nowrap; float: none; direction: ltr; max-width: none; max-height: none; min-width: 0; min-height: 0; border: 0; margin: 0; padding: 1px 0}

.MJXc-display {display: block; text-align: center; margin: 1em 0; padding: 0}

.mjx-chtml[tabindex]:focus, body :focus .mjx-chtml[tabindex] {display: inline-table}

.mjx-full-width {text-align: center; display: table-cell!important; width: 10000em}

.mjx-math {display: inline-block; border-collapse: separate; border-spacing: 0}

.mjx-math \* {display: inline-block; -webkit-box-sizing: content-box!important; -moz-box-sizing: content-box!important; box-sizing: content-box!important; text-align: left}

.mjx-numerator {display: block; text-align: center}

.mjx-denominator {display: block; text-align: center}

.MJXc-stacked {height: 0; position: relative}

.MJXc-stacked > \* {position: absolute}

.MJXc-bevelled > \* {display: inline-block}

.mjx-stack {display: inline-block}

.mjx-op {display: block}

.mjx-under {display: table-cell}

.mjx-over {display: block}

.mjx-over > \* {padding-left: 0px!important; padding-right: 0px!important}

.mjx-under > \* {padding-left: 0px!important; padding-right: 0px!important}

.mjx-stack > .mjx-sup {display: block}

.mjx-stack > .mjx-sub {display: block}

.mjx-prestack > .mjx-presup {display: block}

.mjx-prestack > .mjx-presub {display: block}

.mjx-delim-h > .mjx-char {display: inline-block}

.mjx-surd {vertical-align: top}

.mjx-surd + .mjx-box {display: inline-flex}

.mjx-mphantom \* {visibility: hidden}

.mjx-merror {background-color: #FFFF88; color: #CC0000; border: 1px solid #CC0000; padding: 2px 3px; font-style: normal; font-size: 90%}

.mjx-annotation-xml {line-height: normal}

.mjx-menclose > svg {fill: none; stroke: currentColor; overflow: visible}

.mjx-mtr {display: table-row}

.mjx-mlabeledtr {display: table-row}

.mjx-mtd {display: table-cell; text-align: center}

.mjx-label {display: table-row}

.mjx-box {display: inline-block}

.mjx-block {display: block}

.mjx-span {display: inline}

.mjx-char {display: block; white-space: pre}

.mjx-itable {display: inline-table; width: auto}

.mjx-row {display: table-row}

.mjx-cell {display: table-cell}

.mjx-table {display: table; width: 100%}

.mjx-line {display: block; height: 0}

.mjx-strut {width: 0; padding-top: 1em}

.mjx-vsize {width: 0}

.MJXc-space1 {margin-left: .167em}

.MJXc-space2 {margin-left: .222em}

.MJXc-space3 {margin-left: .278em}

.mjx-test.mjx-test-display {display: table!important}

.mjx-test.mjx-test-inline {display: inline!important; margin-right: -1px}

.mjx-test.mjx-test-default {display: block!important; clear: both}

.mjx-ex-box {display: inline-block!important; position: absolute; overflow: hidden; min-height: 0; max-height: none; padding: 0; border: 0; margin: 0; width: 1px; height: 60ex}

.mjx-test-inline .mjx-left-box {display: inline-block; width: 0; float: left}

.mjx-test-inline .mjx-right-box {display: inline-block; width: 0; float: right}

.mjx-test-display .mjx-right-box {display: table-cell!important; width: 10000em!important; min-width: 0; max-width: none; padding: 0; border: 0; margin: 0}

.MJXc-TeX-unknown-R {font-family: monospace; font-style: normal; font-weight: normal}

.MJXc-TeX-unknown-I {font-family: monospace; font-style: italic; font-weight: normal}

.MJXc-TeX-unknown-B {font-family: monospace; font-style: normal; font-weight: bold}

.MJXc-TeX-unknown-BI {font-family: monospace; font-style: italic; font-weight: bold}

.MJXc-TeX-ams-R {font-family: MJXc-TeX-ams-R,MJXc-TeX-ams-Rw}

.MJXc-TeX-cal-B {font-family: MJXc-TeX-cal-B,MJXc-TeX-cal-Bx,MJXc-TeX-cal-Bw}

.MJXc-TeX-frak-R {font-family: MJXc-TeX-frak-R,MJXc-TeX-frak-Rw}

.MJXc-TeX-frak-B {font-family: MJXc-TeX-frak-B,MJXc-TeX-frak-Bx,MJXc-TeX-frak-Bw}

.MJXc-TeX-math-BI {font-family: MJXc-TeX-math-BI,MJXc-TeX-math-BIx,MJXc-TeX-math-BIw}

.MJXc-TeX-sans-R {font-family: MJXc-TeX-sans-R,MJXc-TeX-sans-Rw}

.MJXc-TeX-sans-B {font-family: MJXc-TeX-sans-B,MJXc-TeX-sans-Bx,MJXc-TeX-sans-Bw}

.MJXc-TeX-sans-I {font-family: MJXc-TeX-sans-I,MJXc-TeX-sans-Ix,MJXc-TeX-sans-Iw}

.MJXc-TeX-script-R {font-family: MJXc-TeX-script-R,MJXc-TeX-script-Rw}

.MJXc-TeX-type-R {font-family: MJXc-TeX-type-R,MJXc-TeX-type-Rw}

.MJXc-TeX-cal-R {font-family: MJXc-TeX-cal-R,MJXc-TeX-cal-Rw}

.MJXc-TeX-main-B {font-family: MJXc-TeX-main-B,MJXc-TeX-main-Bx,MJXc-TeX-main-Bw}

.MJXc-TeX-main-I {font-family: MJXc-TeX-main-I,MJXc-TeX-main-Ix,MJXc-TeX-main-Iw}

.MJXc-TeX-main-R {font-family: MJXc-TeX-main-R,MJXc-TeX-main-Rw}

.MJXc-TeX-math-I {font-family: MJXc-TeX-math-I,MJXc-TeX-math-Ix,MJXc-TeX-math-Iw}

.MJXc-TeX-size1-R {font-family: MJXc-TeX-size1-R,MJXc-TeX-size1-Rw}

.MJXc-TeX-size2-R {font-family: MJXc-TeX-size2-R,MJXc-TeX-size2-Rw}

.MJXc-TeX-size3-R {font-family: MJXc-TeX-size3-R,MJXc-TeX-size3-Rw}

.MJXc-TeX-size4-R {font-family: MJXc-TeX-size4-R,MJXc-TeX-size4-Rw}

.MJXc-TeX-vec-R {font-family: MJXc-TeX-vec-R,MJXc-TeX-vec-Rw}

.MJXc-TeX-vec-B {font-family: MJXc-TeX-vec-B,MJXc-TeX-vec-Bx,MJXc-TeX-vec-Bw}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-ams-R; src: local('MathJax\_AMS'), local('MathJax\_AMS-Regular')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-ams-Rw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_AMS-Regular.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_AMS-Regular.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_AMS-Regular.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-cal-B; src: local('MathJax\_Caligraphic Bold'), local('MathJax\_Caligraphic-Bold')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-cal-Bx; src: local('MathJax\_Caligraphic'); font-weight: bold}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-cal-Bw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Caligraphic-Bold.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Caligraphic-Bold.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Caligraphic-Bold.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-frak-R; src: local('MathJax\_Fraktur'), local('MathJax\_Fraktur-Regular')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-frak-Rw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Fraktur-Regular.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Fraktur-Regular.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Fraktur-Regular.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-frak-B; src: local('MathJax\_Fraktur Bold'), local('MathJax\_Fraktur-Bold')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-frak-Bx; src: local('MathJax\_Fraktur'); font-weight: bold}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-frak-Bw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Fraktur-Bold.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Fraktur-Bold.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Fraktur-Bold.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-math-BI; src: local('MathJax\_Math BoldItalic'), local('MathJax\_Math-BoldItalic')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-math-BIx; src: local('MathJax\_Math'); font-weight: bold; font-style: italic}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-math-BIw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Math-BoldItalic.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Math-BoldItalic.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Math-BoldItalic.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-sans-R; src: local('MathJax\_SansSerif'), local('MathJax\_SansSerif-Regular')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-sans-Rw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_SansSerif-Regular.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_SansSerif-Regular.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_SansSerif-Regular.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-sans-B; src: local('MathJax\_SansSerif Bold'), local('MathJax\_SansSerif-Bold')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-sans-Bx; src: local('MathJax\_SansSerif'); font-weight: bold}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-sans-Bw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_SansSerif-Bold.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_SansSerif-Bold.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_SansSerif-Bold.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-sans-I; src: local('MathJax\_SansSerif Italic'), local('MathJax\_SansSerif-Italic')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-sans-Ix; src: local('MathJax\_SansSerif'); font-style: italic}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-sans-Iw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_SansSerif-Italic.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_SansSerif-Italic.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_SansSerif-Italic.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-script-R; src: local('MathJax\_Script'), local('MathJax\_Script-Regular')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-script-Rw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Script-Regular.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Script-Regular.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Script-Regular.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-type-R; src: local('MathJax\_Typewriter'), local('MathJax\_Typewriter-Regular')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-type-Rw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Typewriter-Regular.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Typewriter-Regular.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Typewriter-Regular.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-cal-R; src: local('MathJax\_Caligraphic'), local('MathJax\_Caligraphic-Regular')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-cal-Rw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Caligraphic-Regular.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Caligraphic-Regular.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Caligraphic-Regular.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-main-B; src: local('MathJax\_Main Bold'), local('MathJax\_Main-Bold')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-main-Bx; src: local('MathJax\_Main'); font-weight: bold}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-main-Bw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Main-Bold.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Main-Bold.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Main-Bold.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-main-I; src: local('MathJax\_Main Italic'), local('MathJax\_Main-Italic')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-main-Ix; src: local('MathJax\_Main'); font-style: italic}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-main-Iw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Main-Italic.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Main-Italic.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Main-Italic.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-main-R; src: local('MathJax\_Main'), local('MathJax\_Main-Regular')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-main-Rw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Main-Regular.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Main-Regular.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Main-Regular.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-math-I; src: local('MathJax\_Math Italic'), local('MathJax\_Math-Italic')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-math-Ix; src: local('MathJax\_Math'); font-style: italic}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-math-Iw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Math-Italic.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Math-Italic.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Math-Italic.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-size1-R; src: local('MathJax\_Size1'), local('MathJax\_Size1-Regular')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-size1-Rw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Size1-Regular.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Size1-Regular.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Size1-Regular.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-size2-R; src: local('MathJax\_Size2'), local('MathJax\_Size2-Regular')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-size2-Rw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Size2-Regular.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Size2-Regular.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Size2-Regular.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-size3-R; src: local('MathJax\_Size3'), local('MathJax\_Size3-Regular')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-size3-Rw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Size3-Regular.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Size3-Regular.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Size3-Regular.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-size4-R; src: local('MathJax\_Size4'), local('MathJax\_Size4-Regular')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-size4-Rw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Size4-Regular.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Size4-Regular.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Size4-Regular.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-vec-R; src: local('MathJax\_Vector'), local('MathJax\_Vector-Regular')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-vec-Rw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Vector-Regular.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Vector-Regular.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Vector-Regular.otf') format('opentype')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-vec-B; src: local('MathJax\_Vector Bold'), local('MathJax\_Vector-Bold')}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-vec-Bx; src: local('MathJax\_Vector'); font-weight: bold}

@font-face {font-family: MJXc-TeX-vec-Bw; src /\*1\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/eot/MathJax\_Vector-Bold.eot'); src /\*2\*/: url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/woff/MathJax\_Vector-Bold.woff') format('woff'), url('https://cdnjs.cloudflare.com/ajax/libs/mathjax/2.7.2/fonts/HTML-CSS/TeX/otf/MathJax\_Vector-Bold.otf') format('opentype')}

, and a protective defensive AI system, with its capabilities quantified p. It may be true that o and p are high, but we also need to care about factors such as p−o and the difference in derivatives dpdresources−dodresources. Some say that future systems will be highly capable, so we do not need to worry about improving their performance in any defensive dimension. Since the relative performance of systems matters and since the scaling laws for safety methods matter, asserting that all variables will be high enough not to worry about them is a low-resolution account of the long term.

Some examples of counteracting systems include artificial consciences, AI watchdogs, lie detectors, filters for power-seeking actions, and separate reward models.

**Rules vs Standards**

*So, we’ve been trying to write tax law for 6,000 years. And yet, humans come up with loopholes and ways around the tax laws so that, for example, our multinational corporations are paying very little tax to most of the countries that they operate in. They find loopholes. And this is what, in the book, I call the loophole principle. It doesn’t matter how hard you try to put fences and rules around the behavior of the system. If it’s more intelligent than you are, it finds a way to do what it wants.*

—[Stuart Russell](https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/2019/10/26/20932289/ai-stuart-russell-human-compatible)

This is true because tax law is exclusively built on *rules*, which are clear, objective, and knowable beforehand. It is built on rules because the government needs to process hundreds of millions of tax returns per year, many tax returns are fairly simple, and people want to have predictability in their taxes. Because rule systems cannot possibly anticipate all loopholes, they are bound to be exploited by intelligent systems. Rules are fragile.

The law has another class of requirements, called [standards](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vgpZ4Y4tEPk), which are designed to address these issues and others. Standards frequently include terms like “reasonable,” “intent,” and “good faith,” which we do not know how to assess in a mechanistic manner. We simply “know it when we see it:” in fact, a common legal term, *res ipsa loquitur*, means “the thing speaks for itself.” Unlike rule-based code, deep neural networks can model these types of fuzzier concepts.

Unlike the tax code, which is based on rules and can be adjudicated by logic-based computer programs such as TurboTax, the criminal law is adjudicated by an intelligent system with intuitions (a judge and perhaps a jury). If a criminal is acquitted when they are guilty, it is because the intelligent system failed to collect enough evidence or interpret it correctly, not because the defense found a “loophole” in the definition of homicide (the exception is when lawyers make mistakes which create trouble under the *rules* used for procedure and evidence).

Russell’s argument correctly concludes that rules alone cannot restrain an intelligent system. However, standards (e.g. “use common sense”, “be reasonable”) can restrain some intelligent behavior, provided the optimizing system is not too much more intelligent than the judiciary. This argument points to the need to have intelligent systems, rather than mechanistic rules, that are able to evaluate other intelligent systems. There are also defensive mechanisms that work for fuzzy raw data, [such as *provable* adversarial robustness](https://arxiv.org/abs/1902.02918), that can help strengthen the defense. It is correct to conclude that an AGI’s objectives should not be based around precise rules, but it does not follow that all objectives are similarly fragile.

**Goal refinement**

Goodhart’s Law applies to *proxies* for what we care about, rather than what we actually care about. Consider [ideal utilitarianism](https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199577446.001.0001/acprof-9780199577446-chapter-4): does Goodhart’s Law show that “maximizing the good” will inevitably lead to ruin? Regardless of how one views ideal utilitarianism, it would be wrong to conclude that it is refuted by Goodhart’s Law, which warns that many *proxies* for good (e.g. “the number of humans who are smiling”) will tend to collapse when subjected to optimization pressure.

Proxies that capture something we care about will likely have an approximation error. Some objectives have more approximation error than others: for instance, if we want to measure economic health, using real GDP reported by the US government will likely have less approximation error than nominal GDP reported in a text file on my computer. When subjected to optimization, that approximation error may become magnified, as optimizers can find areas where the approximation is particularly flawed and potentially manipulate it. This suggests that as optimization power increases, approximation error must correspondingly decrease, which can happen with better models, or approximation errors must become harder to exploit, which can happen with better detectors. As such, systems will need to have their goals continuously refined and improved.

Methods for goal refinement might include better automated moral decision making and value clarification. We will discuss these in our next post.

### Limitations of research based on a hypothetical superintelligence

Many research agendas start by assuming the existence of a superintelligence, and ask how to prove that it is completely safe. Rather than focus on microcosmic existing or soon-to-emerge systems, this line of research analyzes a model in the limit. This line of attack has limitations and should not be the only approach in the portfolio of safety research.

For one, it encourages work in areas which are far less tractable. While mathematical guarantees of safety would be the ideal outcome, there is good reason to believe that in the context of engineering sciences like deep learning, they will be very hard to come by (see the previous posts in the sequence). In information security, practitioners do not look for airtight guarantees of security, but instead try to increase security iteratively as much as possible. Even RSA, the centerpiece of internet encryption, is not provably completely unbreakable (perhaps a superintelligence could find a way to efficiently factor large numbers). Implicitly, the requirement of a proof and only considering worst-case behavior relies on incorrect ideas about Goodhart’s Law: “if it is possible for something to be exploited, it certainly will be by a superintelligence.” As detailed above, this account is overly simplistic and assumes a fixed, rule-based, or unintelligent target.

Second, the assumption of superintelligence eliminates an entire class of interventions which may be needed. It forces a lack of concretization, since it is not certain what kind of system will eventually be superintelligent. This means that feedback loops are extremely sparse, and it is difficult to tell whether any progress is being made. The approach often implicitly incentivizes retrofitting superintelligent systems with safety measures, rather than building safety into pre-superintelligent systems in earlier stages. From complex systems, we know that the crucial variables are often discovered by accident, and only empirical work is able to include the testing and tinkering needed to uncover those variables.

Third, this line of reasoning typically assumes that there will be a single superintelligent agent working directly against us humans. However, there may be multiple superintelligent agents that can rein in other rogue systems. In addition, there may be artificial agents that are above human level on only some dimensions (e.g., creating new chemical or biological weapons), but nonetheless, they could pose existential risks before a superintelligence is created.

Finally, asymptotically-driven research often ignores the effect of technical research on sociotechnical systems. For example, it does very little to improve safety culture among the empirical researchers who will build strong AI, which is a significant opportunity cost. It also is less valuable in cases of (not necessarily existential) crisis, just when policymakers will be looking for workable and time-tested solutions.

Assuming an omnipotent, omniscient superintelligence can be a useful exercise, but it should not be used as the basis for all research agendas.

### Instead, improve cost/benefit variables

In science, problems are rarely solved in one fell swoop. Rather than asking, “does this solve every problem?” we should ask “does this make the current situation better?” Instead of trying to build a technical solution and then try to use it to cause a future AGI to swerve towards safety, we should begin steering towards safety now.

The military and information assurance communities, which are used to dealing with highly adversarial environments, do not search for solutions that render all failures an impossibility. Instead, they often take a cost-benefit analysis approach by aiming to increase the cost of the most pressing types of adversarial behavior. Consequently, a cost-benefit approach is a time-tested way to address powerful intelligent adversaries.

Even though no single factor completely guarantees safety, we can drive down risk through a combination of many safety features (defense in depth). Better adversarial robustness, ethical understanding, safety culture, anomaly detection, and so on to collectively make exploitation by adversaries harder, driving up costs.

In practice, the balance between the costs and benefits of adversarial behavior needs to be tilted in favor of the costs. While it would be nice to have the cost of adversarial behavior be infinite, in practice this is likely infeasible. Fortunately, we just need it to be sufficiently large.

In addition to driving up the cost of adversarial behavior, we should of course drive down the cost of safety features (an important high-level contributing factor). This means making safety features useful in more settings, easier to implement, more reliable, less computationally expensive, or have less steep or no tradeoffs with capabilities. Even if an improvement does not completely solve a safety problem once and for all, we should still aim to continue increasing the benefits. In this way, safety becomes something we can continuously improve, rather than an all-or-nothing binary property.

Some note we “only have one chance to get safety right,” so safety is binary. Of course, there are no do-overs if we’re extinct, so whether or not humans are extinct is indeed binary. However, we believe that the probability of extinction due to an event or deployment is not zero or one, but rather a continuous real value that we can reduce by cautiously changing the costs and benefits of hazardous behavior and safety measures, respectively. The goal should be to reduce risk as much as possible over time.

It’s important to note that not all research areas, including those with clear benefits, will have benefits worth their costs. We will discuss one especially important cost to be mindful of: hastening capabilities and the onset of x-risk.

Safety/capabilities tradeoffs

-----------------------------

Safety and capabilities are linked and can be difficult to disentangle. A more capable system might be more able to understand what humans believe is harmful; it might also have more ability to cause harm. Intelligence cuts both ways. We do understand, however, that desirable behavior *can* be decoupled from intelligence. For example, it is well-known that *moral virtues* are distinct from *intellectual virtues*. An agent that is knowledgeable, inquisitive, quick-witted, and rigorous is not necessarily honest, just, power-averse, or kind.

In this section, by *capabilities* we mean *general capabilities.*These include general prediction, classification, state estimation, efficiency, scalability, generation, data compression, executing clear instructions, helpfulness, informativeness, reasoning, planning, researching, optimization, (self-)supervised learning, sequential decision making, recursive self-improvement, open-ended goals, models accessing the Internet, or similar capabilities. We are not speaking of more specialized capabilities for downstream applications (for instance, climate modeling).

It is not wise to decrease some risks (e.g. improving a safety metric) by increasing other risks through advancing capabilities. In some cases, optimizing safety metrics might increase capabilities even if they aren’t being aimed for, so there needs to be a more principled way to analyze risk. We must ensure that growing the safety field does not simply hasten the arrival of superintelligence.

The figure above shows the performance of various methods on standard ImageNet as well as their anomaly detection performance. The overall trendline shows that anomaly detection performance tends to improve along with more general ImageNet performance, suggesting that one way to make “safety progress” is simply to move along the trendline (see the red dot). However, if we want to make [differentialprogress](https://www.nickbostrom.com/existential/risks.html) towards safety specifically, we should instead focus on safety methods that do not simply move along the existing trend (see the green dot). In addition, the trendline also suggests that differential safety progress is in fact *necessary* to attain maximal anomaly detection performance, since even 100% accuracy would only lead to ~88% AUROC. Consequently researchers will need to shift the line up, not just move along the trendline. This isn’t the whole picture. There may be other relevant axes, such as the ease of a method’s implementation, its computational cost, its extensibility, and its data requirements. However, the leading question should be to ask what the effect of a safety intervention is on general capabilities.

It’s worth noting that safety is commercially valuable: systems viewed as safe are more likely to be deployed. As a result, even improving safety without improving capabilities could hasten the onset of x-risks. However, this is a very small effect compared with the effect of directly working on capabilities. In addition, hypersensitivity to any onset of x-risk proves too much. One could claim that any discussion of x-risk at all draws more attention to AI, which could hasten AI investment and the onset of x-risks. While this may be true, it is not a good reason to give up on safety or keep it known to only a select few. We should be precautious but not self-defeating.

### Examples of capabilities goals with safety externalities

[Self-supervised learning](https://arxiv.org/abs/1906.12340) and [pretraining](https://arxiv.org/abs/2004.06100) have been shown to improve various uncertainty and robustness metrics. However, the techniques were developed primarily for the purpose of advancing general capabilities. This shows that it is not necessary to be aiming for safety to improve it, and certain upstream capabilities improvements can simply improve safety “accidentally.”

Improving world understanding helps models better anticipate consequences of their actions. It thus makes it less likely that they will produce unforeseen consequences or take irreversible actions. However, it also increases their power to influence the world, potentially increasing their ability to produce undesirable consequences.

Note that in some cases, even if research is done with a safety goal, it might be indistinguishable from research done with a capabilities goal if it simply moves along the existing trendlines.

### Examples of safety goals with capabilities externalities