id

stringlengths 36

36

| source

stringclasses 15

values | formatted_source

stringclasses 13

values | text

stringlengths 2

7.55M

|

|---|---|---|---|

c95f61d7-f8d9-4755-92c1-4e81412631c6

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

[AN #69] Stuart Russell's new book on why we need to replace the standard model of AI

Find all Alignment Newsletter resources here. In particular, you can sign up, or look through this spreadsheet of all summaries that have ever been in the newsletter. I'm always happy to hear feedback; you can send it to me by replying to this email.

This is a bonus newsletter summarizing Stuart Russell's new book, along with summaries of a few of the most relevant papers. It's entirely written by Rohin, so the usual "summarized by" tags have been removed.

We're also changing the publishing schedule: so far, we've aimed to send a newsletter every Monday; we're now aiming to send a newsletter every Wednesday.

Audio version here (may not be up yet).

Human Compatible: Artificial Intelligence and the Problem of Control (Stuart Russell): Since I am aiming this summary for people who are already familiar with AI safety, my summary is substantially reorganized from the book, and skips large portions of the book that I expect will be less useful for this audience. If you are not familiar with AI safety, note that I am skipping many arguments and counterarguments in the book that are aimed for you. I'll refer to the book as "HC" in this newsletter.

Before we get into details of impacts and solutions to the problem of AI safety, it's important to have a model of how AI development will happen. Many estimates have been made by figuring out the amount of compute needed to run a human brain, and figuring out how long it will be until we get there. HC doesn't agree with these; it suggests the bottleneck for AI is in the algorithms rather than the hardware. We will need several conceptual breakthroughs, for example in language or common sense understanding, cumulative learning (the analog of cultural accumulation for humans), discovering hierarchy, and managing mental activity (that is, the metacognition needed to prioritize what to think about next). It's not clear how long these will take, and whether there will need to be more breakthroughs after these occur, but these se

|

91917dc6-38e1-4c3f-8b00-eac8e5899a90

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

The affect heuristic and studying autocracies

General Juan Velasco Alvarado was the military dictator of Peru from 1968 to 1975. In 1964-5 he put down revolutionary peasant guerilla movements, defending an unequal and brutally exploitative pattern of land ownership. Afterward he became frustrated with the bickering and gridlock of Peru’s parliament. With a small cadre of military coconspirators, he planned a coup d’état. Forestalling an uprising by pro-peasant parties, he sent tanks to kidnap the democratically elected president. The parliament was closed indefinitely. On the one year anniversary of his coup, Velasco stated “Some people expected very different things and were confident, as had been the custom, that we came to power for the sole purpose of calling elections and returning to them all their privileges. The people who thought that way were and are mistaken”.[1]

What would you expect Velasco’s policy toward land ownership and peasants to be? You would probably expect him to continue their exploitation by the oligarchy land-owning families. But you would be mistaken. Velasco and his successor redistributed 45% of all arable land in Peru to peasant lead communes, which were later broken up. Land redistribution is a rare spot of consensus in development economics, improving both the lives of the poor and increasing growth. [2]

I told you this story to highlight how your attitudes toward the actor affect your predictions. It is justifiable to dislike Velasco for his violence, for ending Peruvian democracy, for his state-controlled economy. But our brains predict off of those value judgements. The affect heuristic (aka the halo/horn effect) is when one positive/negative attribute of an actor causes people to assume positive/negative attributes in another area. The affect heuristic causes attractive candidates to be hired more often, or honest people to be rated as more intelligent. Subjects told about the benefit of nuclear power are likely to rate it as having fewer risks, et cetera. Our moral attitud

|

f910b043-702f-4891-805a-2d21b1934a37

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

The call of the void

Original post: http://bearlamp.com.au/the-call-of-the-void

L'appel du vide - The call of the void.

When you are standing on the balcony of a tall building, looking down at the ground and on some track your brain says "what would it feel like to jump". When you are holding a kitchen knife thinking, "I wonder if this is sharp enough to cut myself with". When you are waiting for a train and your brain asks, "what would it be like to step in front of that train?". Maybe it's happened with rope around your neck, or power tools, or what if I take all the pills in the bottle. Or touch these wires together, or crash the plane, crash the car, just veer off. Lean over the cliff... Try to anger the snake, stick my fingers in the moving fan... Or the acid. Or the fire.

There's a strange phenomenon where our brains seem to do this, "I wonder what the consequences of this dangerous thing are". And we don't know why it happens. There has only been one paper (sorry it's behind a paywall) on the concept. Where all they really did is identify it. I quite like the paper for quoting both (“You know that feeling you get when you're standing in a high place… sudden urge to jump?… I don't have it” (Captain Jack Sparrow, Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides, 2011). And (a drive to return to an inanimate state of existence; Freud, 1922).

Taking a look at their method; they surveyed 431 undergraduates for their experiences of what they coined HPP (High Place Phenomenon). They found that 30% of their constituents have experienced HPP, and tried to measure if it was related to anxiety or suicide. They also proposed a theory.

> ...we propose that at its core, the experience of the high place phenomenon stems from the misinterpretation of a safety or survival signal. (e.g., “back up, you might fall”)

I want to believe it, but today there are Literally no other papers on the topic. And no evidence either way. So all I can say is - We don't really know. s'weird. Du

|

58af1931-e7cf-4a9d-bdf5-2f004d22724a

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

App idea to help with reading STEM textbooks (feedback request)

Problem: STEM textbooks often reference figures and equations from earlier in the textbook. They usually do this with statements like "the shearing stress τ... may be obtained from the shearing-stress-strain diagram of Fig. 3.30." But Fig. 3.30 might be from 5 pages ago, or even earlier. Many textbooks don't have a list or index of equations, so the only way to find the referenced figure is to search page by page.

How this would ideally be solved: Every textbook would have an e-book version that links to, and previews, referenced equations every time they are mentioned.

Why not do this: Different textbooks identify and reference figures and equations different ways. Many readers of e-books use DRM-protected apps. These make it hard to create a universal solution that automatically identifies and annotates texts to provide this functionality. In addition, building an e-reader with this functionality requires building an e-reader to display PDFs and other formats, which seems very hard.

How I suspect most people solve the problem: Most people probably deal with this more or less like I do. The struggle to be diligent and actually look up the referenced figure. They might try to memorize the information. They also might put it into a list of reference notes containing the equations.

Why these solutions are suboptimal: Trying to look up or memorize information is cognitively and motivationally challenging. Learning dense material is already hard, and this adds to the burden. Taking notes can help. However, this leads to visual clutter when most equations aren't necessary at a given time, or when material that needs to be looked at simultaneously is distributed across different pages of notes. It's not always easy to get the required information into the note-taking system. Some note-taking systems also have trouble managing the sort of information a STEM student might need.

How this new app would solve the problem: This app depends on a "snip" feature, where we tak

|

098031b0-cc54-44c0-9aab-706b6411aadd

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

[Link] Intro to causal inference by Michael Nielsen (2012)

This is a link post for Michael Nielsen's "If correlation doesn’t imply causation, then what does?" (2012).

I want to highlight the post for a few reasons:

(1) it is a well-written introduction by an experienced science communicator — Michael is an author of the most famous book on quantum computing;

(2) causal inference is an essential tool for understanding the world;

(3) two recent AI safety papers use causal influence diagrams to (a) understand agent incentives [arXiv, Medium] and (b) to provide a new perspective on some problems in AGI safety [arXiv].

|

57a251bd-f688-48d4-8183-4ea0e5145b05

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

Against Cryonics & For Cost-Effective Charity

Related To: You Only Live Twice, Normal Cryonics, Abnormal Cryonics, The Threat Of Cryonics, Doing your good deed for the day, Missed opportunities for doing well by doing good

Summary: Many Less Wrong posters are interested in advocating for cryonics. While signing up for cryonics is an understandable personal choice for some people, from a utilitarian point of view the money spent on cryonics would be much better spent by donating to a cost-effective charity. People who sign up for cryonics out of a generalized concern for others would do better not to sign up for cryonics and instead donating any money that they would have spent on cryonics to a cost-effective charity. People who are motivated by a generalized concern for others to advocate the practice of signing up for cryonics would do better to advocate that others donate to cost-effective charities.

Added 08/12: The comments to this post have prompted me to add the following disclaimers:

(1) Wedrifid understood me to be placing moral pressure on people to sacrifice themselves for the greater good. As I've said elsewhere, "I don't think that Americans should sacrifice their well-being for the sake of others. Even from a utilitarian point of view, I think that there are good reasons for thinking that it would be a bad idea to do this." My motivation for posting on this topic is the one described by rhollerith_dot_com in his comment.

(2) In line with the above comment, when I say "selfish" I don't mean it with the negative moral connotations that the word carries, I mean it as a descriptive term. There are some things that we do for ourselves and there are some things that we do for others - this is as things should be. I'd welcome any suggestions for a substitute for the word "selfish" that has the same denotation but which is free of negative conotations.

(3) Wei_Dai thought that my post assumed a utilitarian ethical framework. I can see how my post may have come across that way. However, while writing

|

b227a77d-c4ad-4d5f-883a-1fe240bf6f8f

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

Meetup : Different location for Berkeley meetup

Discussion article for the meetup : Different location for Berkeley meetup

WHEN: 17 October 2012 07:00:00PM (-0700)

WHERE: 2128 Oxford St, Berkeley, CA

Today Zendo and I are unavailable. Several people on the mailing list have suggested that people meet at the Starbucks on Center and Oxford Street at 7pm. You should come there if your coming there acausally implies that other people will come there.

Discussion article for the meetup : Different location for Berkeley meetup

|

d00bcf66-6360-48be-8a72-c025ce414cf1

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

Decent plan prize announcement (1 paragraph, $1k)

Edit Jan 20: Winner & highlights

Say I'm about to do a real big training run on playing video games, predicting text, predicting physics, writing code that works, etc etc. Say I've got a real good neural net architecture and a whole lot of flops. Say I'm a company and I'm gonna use this thing for AI lawyers and coders etc for a profit. Say I'm mildly concerned it somehow kills me and am willing to throw a few $ to prevent that.

So what should I do? How should I train and deploy the model?

Comment below or answer at this link if you don't want to be plagiarized.

Prize goes to best answer. (I judge obviously.)

The shorter the answer the better.

Deadline is Wednesday January 17 anywhere on Earth but answering immediately is better/easier.

You may accept your prize as 50 pounds of quarters if you prefer.

----------------------------------------

Clarification jan 12: say I've got 1000x the gpt4 flops and that my architecture is to transformers as convolutions are to simple MLPs in vision (ie a lot better)

Clarification 2: an answer like "here's how to get strong evidence of danger so you know when to stop training" is valid but "here's how to wipe out the danger" is much better.

3: Example answer for nuclear generators: "Spring-load your control rods so they are inserted when power goes out. Build giant walls around reactor so if steam explodes then uranium doesn't go everywhere. Actually, use something low pressure instead if possible, like molten salt or boiling water. Lift the whole thing off the ground to avoid flood risk."

4: This is hypothetical. I am not actually doing this. I'm not a billionaire.

5: "Hire someone" and "contract it out " and "develop expertise" etc obviously do not count as answers.

|

b5522b28-cea5-42fb-a2c2-6fe0410277a6

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

A very non-technical explanation of the basics of infra-Bayesianism

Introduction

As a response to John Wentworth's public request, I try to explain the basic structure of infra-Bayesian decision-making in a nutshell. Be warned that I significantly simplify some things, but I hope it gives roughly the right picture.

This post is mostly an abridged version of my previous post Performance guarantees in in classical learning and infra-Bayesianism. If you are interested in the more detailed and less sloppy version, you can read it there, it's a little more technical, but still accessible without serious background knowledge.

I also wrote up my general thoughts and criticism on infra-Bayesianism, and a shorter post explaining how infra-Bayesianism leads to the monotonicity principle.

Classical learning theory

Infra-Bayesianism was created to address some weak spots in classical learning theory. Thus, we must start by briefly talking about learning theory in general.

In classical learning theory, the agent has a hypothesis class, each hypothesis giving a full description of the environment. The agent interacts with the environment for a long time, slowly accumulating loss corresponding to certain events. The agent has a time discount rate γ, and its overall life-time loss is calculated by weighing the losses it receives through its history by this time discount.

The regret of an agent in environment e is the difference between the loss the agent actually receives through its life, and the loss it would receive if it followed the policy that is optimal for the environment e.

We say that a policy successfully learns a hypothesis class H, if it has low expected regret with respect to every environment e described in the hypothesis class.

How can a policy achieve this? In the beginning, the agent takes exploratory steps and observes the environment. If the observations are much more likely in environment e1 than in environment e2, then the agent starts acting in ways that make more sense in environment e1, and starts paying less atten

|

a25e82a2-77f3-4080-9b72-628a6dc42be1

|

StampyAI/alignment-research-dataset/lesswrong

|

LessWrong

|

What achievements have people claimed will be warning signs for AGI?

In MIRI's March newsletter, they link [this post](https://www.technologyreview.com/s/615264/artificial-intelligence-destroy-civilization-canaries-robot-overlords-take-over-world-ai/) which argues against the importance of AI safety because we haven't yet achieved a number of "canaries in the coal mines of AI". The post lists:

* The automatic formulation of learning problems

* Self-driving cars

* AI doctors

* Limited versions of the Turing test

What other sources identify warning signs for the development of AGI?

|

3f8f2365-44a2-401e-a0c8-5af946c6d7a8

|

StampyAI/alignment-research-dataset/alignmentforum

|

Alignment Forum

|

Engineering Monosemanticity in Toy Models

Overview

========

In some neural networks, individual neurons correspond to natural "features" in the input. Such *monosemantic* neurons are much easier to interpret, because in a sense they only do one thing. By contrast, some neurons are *polysemantic*, meaning that they fire in response to multiple unrelated features in the input. Polysemantic neurons are much harder to characterize because they can serve multiple distinct functions in a network.

Recently, [Elhage+22](https://transformer-circuits.pub/2022/toy_model/index.html) and [Scherlis+22](https://arxiv.org/abs/2210.01892) demonstrated that architectural choices can affect monosemanticity, raising the prospect that we might be able to engineer models to be more monosemantic. In this work we report preliminary attempts to engineer monosemanticity in toy models.

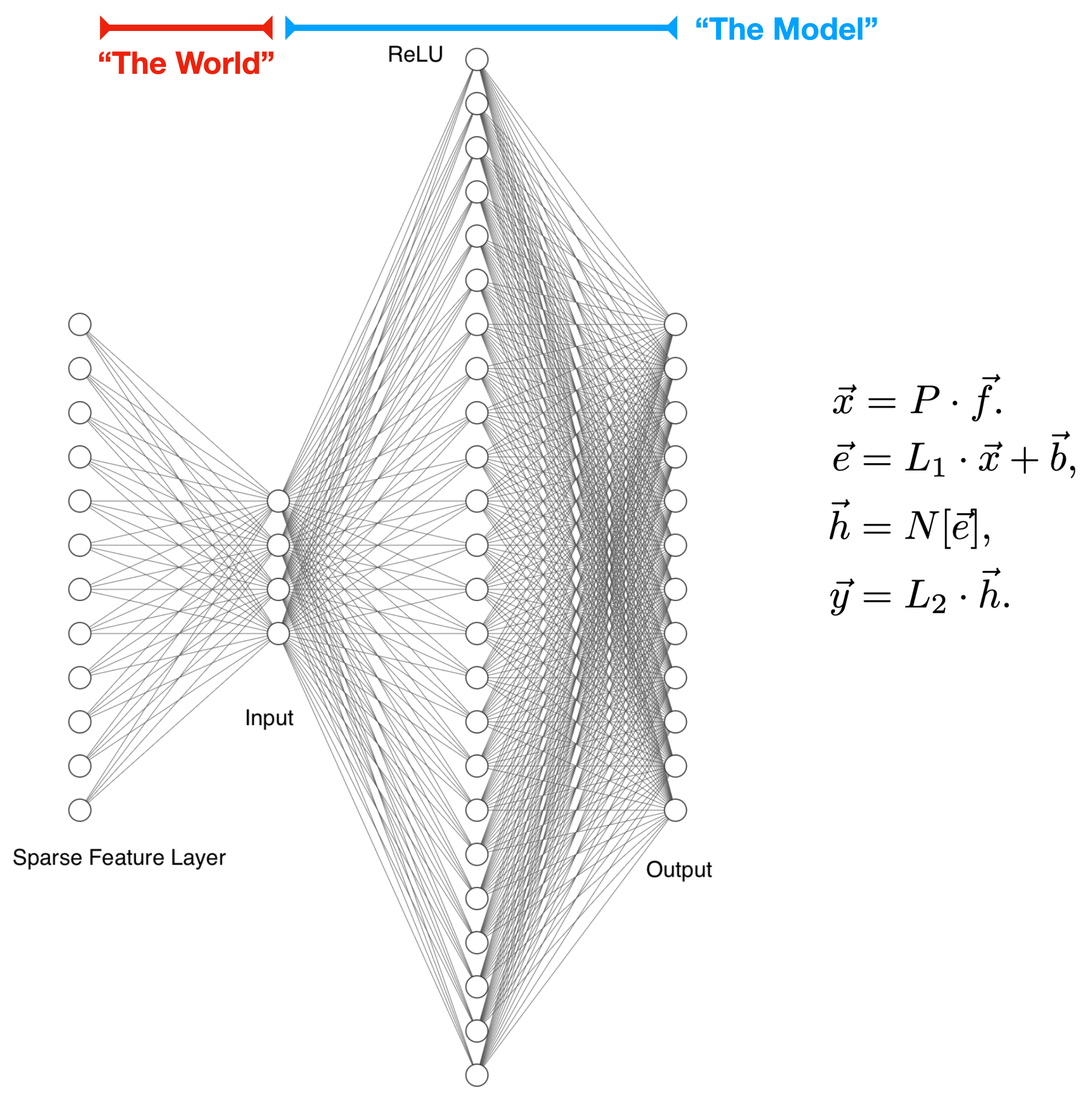

Toy Model

=========

The simplest architecture that we could study is a one-layer model. However, a core question we wanted to answer is: how does the number of neurons (nonlinear units) affect the degree of monosemanticity? To that end, we use a two-layer architecture:

Features are generated as sparse vectors in a high-dimensional space. They are then run through a (fixed) random projection layer to produce the inputs into our model. We imagine this random projection process as an analogy to the way the world encodes features in our observations.

Within the model, the first layer is a linear transformation with a bias, followed by a nonlinearity. The second layer is a linear transformation with no bias.

Our toy model is most similar to that of Elhage+22, with a key difference being that the extra linear layer allows us to vary the number of neurons independent of the number of features or the input dimension.

We study this two model on three tasks. The first, a feature decoder, performs a compressed sensing reconstruction of features that were randomly and lossily projected into a low-dimensional space. The second, a random re-projector, reconstructs one fixed random projection of features from a different fixed random projection. The third, an absolute value calculator, performs the same compressed sensing task and then returns the absolute values of the recovered features. These tasks have the important property that we know which features are naturally useful, and so can easily measure the extent to which neurons are monosemantic or polysemantic.

Note that we primarily study the regime where there are more features than embedding dimensions (i.e. the sparse feature layer is wider than the input) but where features are sufficiently sparse that the number of features present in any given sample is smaller than the embedding dimension. We think this is likely the relevant limit for e.g. language models, where there are a vast array of possible features but few are present in any given sample.

Key Results

===========

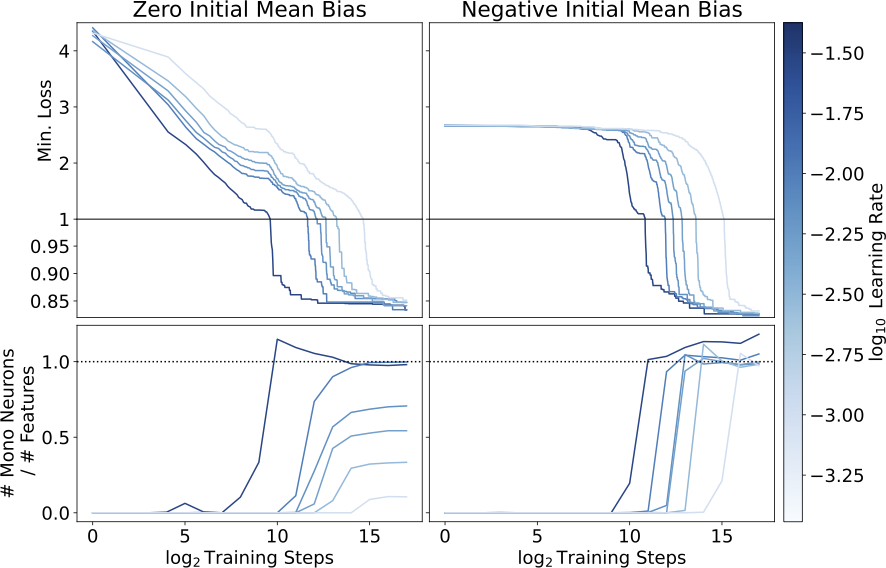

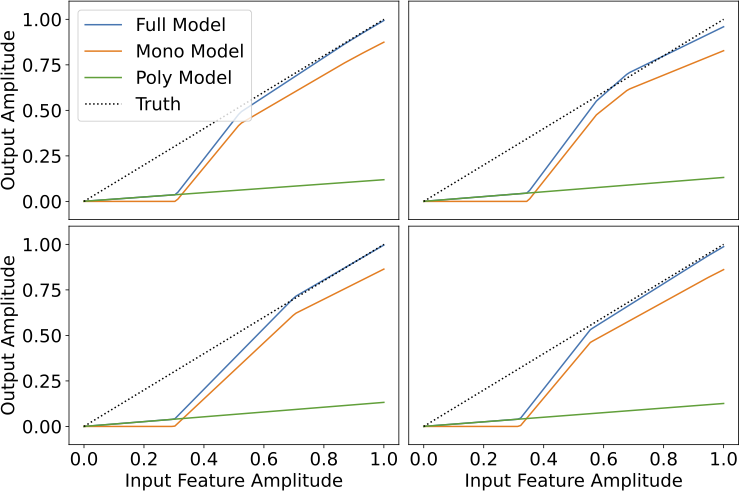

We find that models initialized with zero mean bias (left) find different local minima depending on the learning rate, with more monosemantic solutions and slightly lower loss at higher learning rates. Models initialized with a negative mean bias (right) all find highly monosemantic local minima, and achieve slightly better loss. Note that these models are all in a regime where they have more neurons than there are input features.

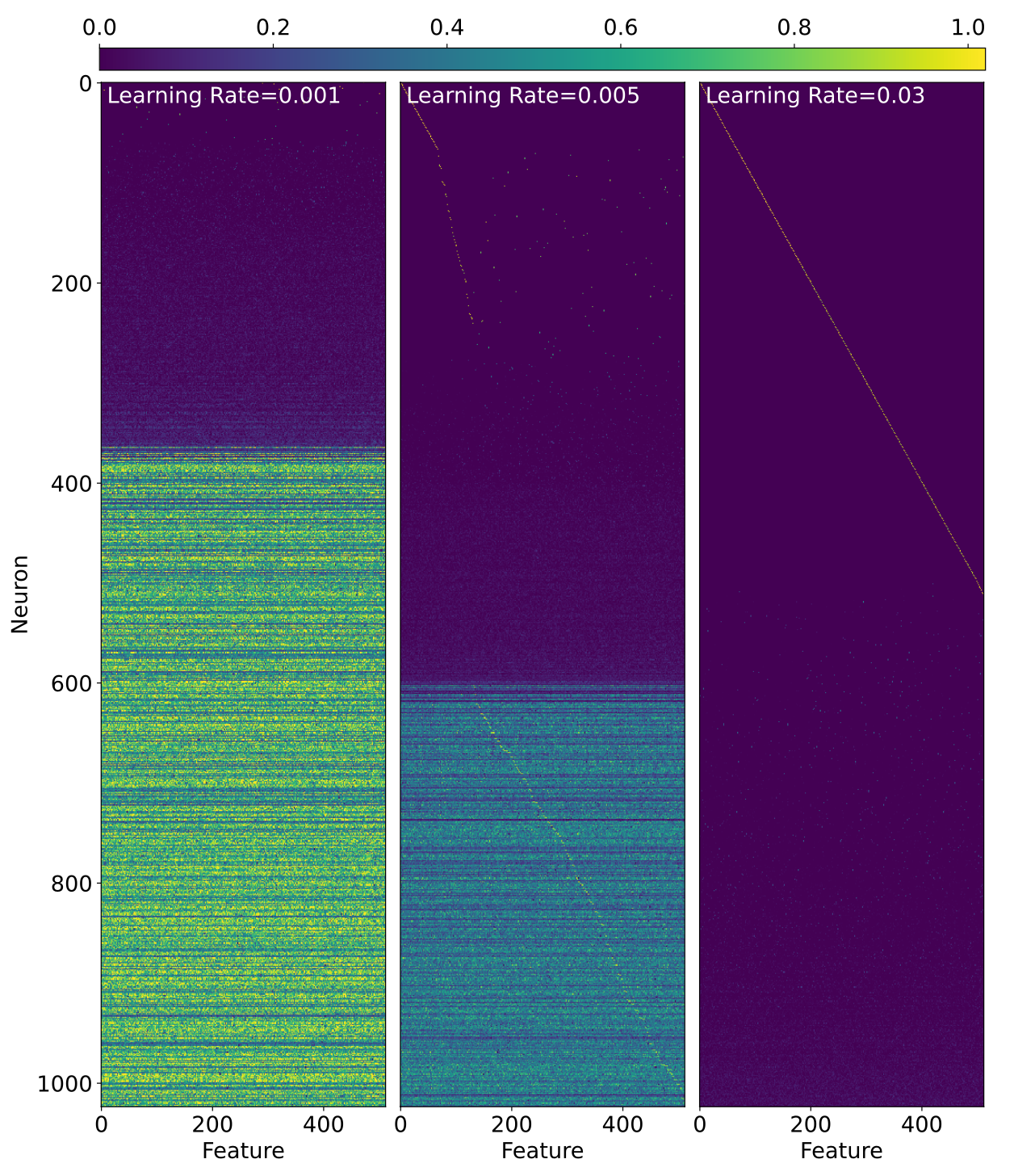

Just to hammer home how weird this is, below we've plotted the activations of neurons in response to single-feature inputs. The three models we show get essentially the same loss but are clearly doing very different things!

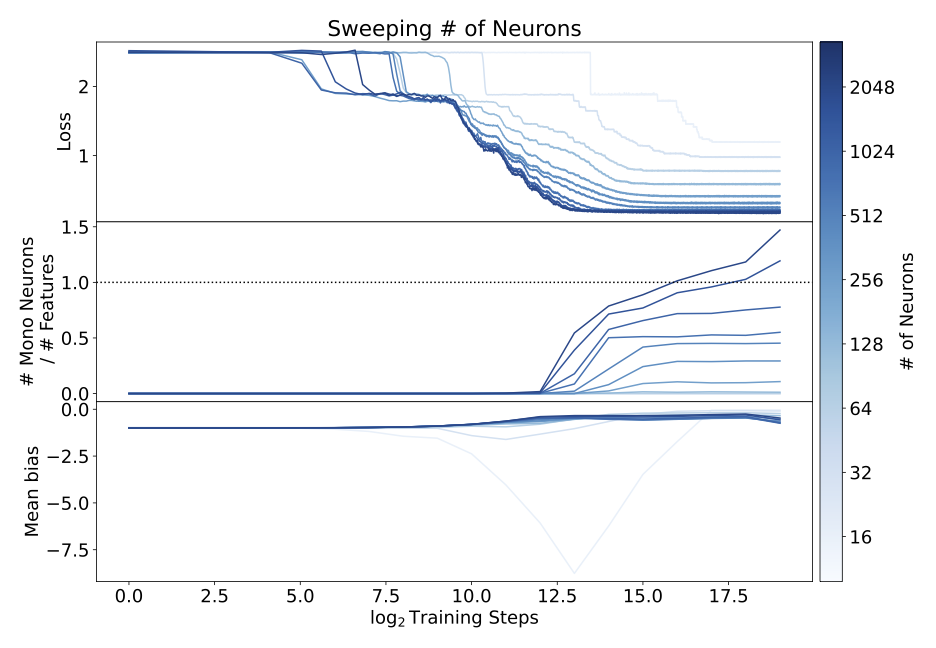

More generally, we find:

1. When inputs are feature-sparse, models can be made more monosemantic with no degredation in performance by just changing which loss minimum the training process finds (Section 4.1.1).

2. More monosemantic loss minima have moderate negative biases in all three tasks, and we are able to use this fact to engineer highly monosemantic models (Section 4.1.2).

3. Providing models with more neurons per layer makes the models more monosemantic, albeit at increased computational cost (Section 4.1.4, also see below).

Interpretability

================

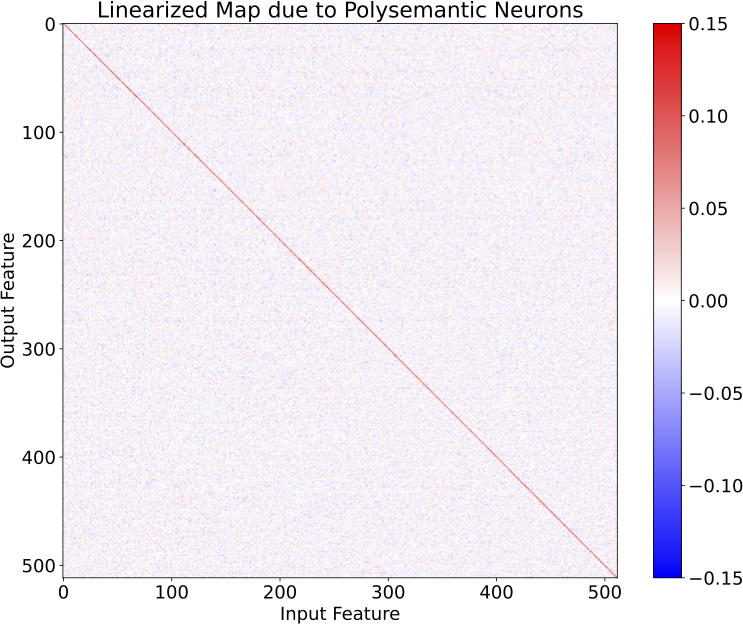

In Section 5 we provide some mechanistic interpretability results for our feature decoder models in the monosemantic limit. In this toy model setting we can decompose our model into a monosemantic part and a polysemantic part, and plotting these separately feature-by-feature is revealing:

From this, we find that:

1. When there is a single monosemantic neuron for a feature, that neuron implements a simple algorithm of balancing feature recovery against interference.

2. When there are two monosemantic neurons for a feature, those neurons together implement an algorithm that classifies potential features as ``likely real'' or ``likely interference'', and then recovers the strength of any ``likely real'' features.

Additionally, we were suspicious at how few kinks the polysemantic neurons provided to the model's output. Indeed plotting the linearized map that these neurons implement reveals that they primarily serve to implement a low-rank approximation to the identity, which allows the model to have non-zero confidence in features at low input amplitudes:

Future Work

===========

We think there's a lot of low-hanging fruit in the direction of "engineer models to be more monosemantic", and we're excited to pick some more of it. The things we're most excited about include:

1. Our approach to engineering monosemanticity through bias could be made more robust by tailoring the bias weight decay on a per-neuron basis, or tying it to the rate of change of the rest of the model weights.

2. We've had some luck with an approach of the form "Engineer models to be more monosemantic, then interpret the remaining polysemantic neurons. Figure out what they do, re-architect the model to make that a monosemantic function, and interpret any new polysemantic neurons that emerge." We think we're building useful intuition playing this game, and are hopeful that there might be some more general lessons to be learned from it.

3. We have made naive attempts to use sparsity to reduce the cost of having more neurons per layer, but these degraded performance substantially. It is possible that further work in this direction will yield more workable solutions.

We'd be excited to answer questions about our work or engage with comments/suggestions for future work, so please don't be shy!

|

8cb00231-f092-477e-bbad-65a43e799653

|

trentmkelly/LessWrong-43k

|

LessWrong

|

Meetup : Vancouver meetup

Discussion article for the meetup : Vancouver meetup

WHEN: 06 August 2011 03:00:00PM (-0700)

WHERE: Waves Coffee House, 100-900 Howe St. Vancouver, BC V6Z 2M4

Last Sunday's first Vancouver rationalist meetup was great! Seven people turned up and we talked about the Singularity, Bitcoin, seasteading, polyamory, the Khan Academy, the Hanson/Caplan view that education is more about signaling than imparting knowledge, Non-Violent Communication, akrasia, nootropics, our favorite Less Wrong posts and authors, and many other things.

I think we have the beginnings of a lasting community. If you're interested, join the Vancouver Rationalists Google Group to plan meetups and for general discussion.

Sunday afternoon was not convenient for everyone, and a Doodle poll shows Saturday as the better option. So we'll meet at 3pm on Saturday (sorry about the short notice if you're just hearing about this now).

We have a meeting room booked at the Waves Coffee House on the corner of Howe St. and Smithe.

This week's discussion topic is:

Tell your rationality success story or failure story. Describe a time when rationality helped (or hurt) you, or a time when irrationality hurt (or helped) you, and what lessons might be drawn from the experience.

Feel free to bring friends who are interested in rationality.

Discussion article for the meetup : Vancouver meetup

|

9bc46f27-1dcf-413e-9820-e9cc263a583a

|

StampyAI/alignment-research-dataset/arxiv

|

Arxiv

|

APS: Active Pretraining with Successor Features.

1 Introduction

---------------

Figure 1:

Median of human normalized score on the 26 Atari games considered by Kaiser et al. ([2020](#bib.bib33)) (left) and the Atari 57 games considered in Mnih et al. ([2015](#bib.bib44))(right).

Fully supervised RL baselines are shown in circle.

RL with unsupervised pretraining are shown in square.

APS significantly outperforms all of the fully supervised and unsupervised pre-trained RL methods.

Baselines: Rainbow (Hessel et al., [2018](#bib.bib29)), SimPLe (Kaiser et al., [2020](#bib.bib33)), APT (Liu & Abbeel, [2021](#bib.bib42)), Data-efficient Rainbow (Kielak, [2020](#bib.bib34)), DrQ (Kostrikov et al., [2020](#bib.bib36)), VISR (Hansen et al., [2020](#bib.bib26)), CURL (Laskin et al., [2020](#bib.bib38)), and SPR (Schwarzer et al., [2021](#bib.bib52)).

Deep unsupervised pretraining has achieved remarkable success in various frontier AI domains from natural language processing (Devlin et al., [2019](#bib.bib23); Peters et al., [2018](#bib.bib49); Brown et al., [2020](#bib.bib15)) to computer vision (He et al., [2020](#bib.bib28); Chen et al., [2020a](#bib.bib19)).

The pre-trained models can quickly solve downstream tasks through few-shot fine-tuning (Brown et al., [2020](#bib.bib15); Chen et al., [2020b](#bib.bib20)).

In reinforcement learning (RL), however, training from scratch to maximize extrinsic reward is still the dominant paradigm.

Despite RL having made significant progress in

playing video games (Mnih et al., [2015](#bib.bib44); Schrittwieser et al., [2019](#bib.bib51); Vinyals et al., [2019](#bib.bib59); Badia et al., [2020a](#bib.bib4)) and solving complex robotic control tasks (Andrychowicz et al., [2017](#bib.bib3); Akkaya et al., [2019](#bib.bib2)), RL algorithms have to be trained from scratch to maximize extrinsic return for every encountered task.

This is in sharp contrast with how intelligent creatures quickly adapt to new tasks by leveraging previously acquired behaviors.

In order to bridge this gap, unsupervised pretraining RL has gained interest recently, from state-based (Gregor et al., [2016](#bib.bib25); Eysenbach et al., [2019](#bib.bib24); Sharma et al., [2020](#bib.bib54); Mutti et al., [2020](#bib.bib46)) to pixel-based RL (Hansen et al., [2020](#bib.bib26); Liu & Abbeel, [2021](#bib.bib42); Campos et al., [2021](#bib.bib18)).

In unsupervised pretraining RL,

the agent is allowed to train for a long period without access to environment reward, and then got exposed to reward during testing.

The goal of pretraining is to have data efficient adaptation for some downstream task defined in the form of rewards.

State-of-the-art unsupervised RL methods consider various ways of designing the so called intrinsic reward (Barto et al., [2004](#bib.bib11); Barto, [2013](#bib.bib10); Gregor et al., [2016](#bib.bib25); Achiam & Sastry, [2017](#bib.bib1)), with the goal that maximizing this intrinsic return can encourage meaningful behavior in the absence of external rewards.

There are two lines of work in this direction, we will discuss their advantages and limitations, and show that a novel combination yields an effective algorithm which brings the best of both world.

The first category is based on maximizing the mutual information between task variables (p(z)) and their behavior in terms of state visitation (p(s)) to encourage learning distinguishable task conditioned behaviors, which has been shown effective in state-based RL (Gregor et al., [2016](#bib.bib25); Eysenbach et al., [2019](#bib.bib24)) and visual RL (Hansen et al., [2020](#bib.bib26)).

VISR proposed in Hansen et al. ([2020](#bib.bib26)) is the prior state-of-the-art in this category.

The objective of VISR is maxI(s;z)=maxH(z)−H(s|z) where z is sampled from a fixed distribution.

VISR proposes a successor features based variational approximation to maximize a variational lower bound of the intractable conditional entropy −H(s|z).

The advantage of VISR is that its successor features can quickly adapt to new tasks.

Despite its effectiveness, the fundamental problem faced by VISR is lack of exploration.

Another category is based on maximizing the entropy of the states induced by the policy maxH(s).

Maximizing state entropy has been shown to work well in state-based domains (Hazan et al., [2019](#bib.bib27); Mutti et al., [2020](#bib.bib46)) and pixel-based domains (Liu & Abbeel, [2021](#bib.bib42)).

It is also shown to be provably efficient under certain assumptions (Hazan et al., [2019](#bib.bib27)).

The prior state-of-the-art APT by Liu & Abbeel ([2021](#bib.bib42)) show maximizing a particle-based entropy in a lower dimensional abstraction space can boost data efficiency and asymptotic performance.

However, the issues with APT are that it is purely exploratory and task-agnostic and lacks of the notion of task variables, making it more difficult to adapt to new tasks compared with task-conditioning policies.

Our main contribution is to address the issues of APT and VISR by combining them together in a novel way.

To do so, we consider the alternative direction of maximizing mutual information between states and task variables I(s;z)=H(s)−H(s|z),

the state entropy H(s) encourages exploration while the conditional entropy encourages the agent to learn task conditioned behaviors.

Prior work that considered this objective had to either make the strong assumption that the distribution over states can be approximated with the stationary state-distribution of the

policy (Sharma et al., [2020](#bib.bib54)) or rely on the challenging density modeling to derive a tractable lower bound (Sharma et al., [2020](#bib.bib54); Campos et al., [2020](#bib.bib17)). We show that

the intractable conditional entropy, −H(s|z) can be lower bounded and optimized by learning successor features.

We use APT to maximize the state entropy H(s) in an abstract representation space.

Building upon this insight, we propose Active Pretraining with Successor Features (APS) since the agent is encouraged to actively explore and leverage the experience to learn behavior.

By doing so, we experimentally find that they address the limitations of each other and significantly improve each other.

We evaluate our approach on the Atari benchmark (Bellemare et al., [2013](#bib.bib13)) where we apply APS to DrQ (Kostrikov et al., [2020](#bib.bib36)) and test its performance after fine-tuning for 100K supervised environment steps.

The results are shown in Figure [1](#S1.F1 "Figure 1 ‣ 1 Introduction ‣ APS: Active Pretraining with Successor Features").

On the 26 Atari games considered by (Kaiser et al., [2020](#bib.bib33)), our fine-tuning significantly boosts the data-efficiency of DrQ, achieving 106% relative improvement.

On the full suite of Atari 57 games (Mnih et al., [2015](#bib.bib44)), fine-tuning APS pre-trained models significantly outperforms prior state-of-the-art, achieving human median score 3× higher than DQN trained with 10M supervised environment steps and outperforms previous methods combining unsupervised pretraining with task-specific finetuning.

2 Related Work

---------------

Our work falls under the category of mutual information maximization for unsupervised behavior learning.

Unsupervised discovering of a set of task-agnostic behaviors by means of seeking to maximize an extrinsic reward has been explored in the the evolutionary computation community (Lehman & Stanley, [2011a](#bib.bib40), [b](#bib.bib41)).

This has long been studied as intrinsic motivation (Barto, [2013](#bib.bib10); Barto et al., [2004](#bib.bib11)), often with the goal of encouraging exploration (Simsek & Barto, [2006](#bib.bib55); Oudeyer & Kaplan, [2009](#bib.bib47)).

Entropy maximization in state space has been used to encourage exploration in state RL (Hazan et al., [2019](#bib.bib27); Mutti et al., [2020](#bib.bib46); Seo et al., [2021](#bib.bib53)) and visual RL (Liu & Abbeel, [2021](#bib.bib42); Yarats et al., [2021](#bib.bib61)).

Maximizing the mutual information between latent variable policies and their behavior in terms of state visitation has been used as an objective for discovering meaningful behaviors (Houthooft et al., [2016a](#bib.bib31); Mohamed & Rezende, [2015](#bib.bib45); Gregor et al., [2016](#bib.bib25); Houthooft et al., [2016b](#bib.bib32); Eysenbach et al., [2019](#bib.bib24); Warde-Farley et al., [2019](#bib.bib60)).

Sharma et al. ([2020](#bib.bib54)) consider a similar decomposition of mutual information, namely, I(s;z)=H(s)−H(z|s), however, they assume p(s|z)≈p(s) to derive a different lower-bound of the marginal entropy.

Different from Sharma et al. ([2020](#bib.bib54)),

Campos et al. ([2020](#bib.bib17)) propose to first maximize H(s) via maximum entropy estimation (Hazan et al., [2019](#bib.bib27); Lee et al., [2019](#bib.bib39)) then learn behaviors, this method relies on a density model that provides an estimate of how many times an action has been taken in similar states.

These methods are also only shown to work from explicit state-representations, and it is nonobvious how to modify them to work from pixels.

The work by Badia et al. ([2020b](#bib.bib5)) also considers k-nearest neighbor based count bonus

to encourage exploration, yielding improved performance on Atari games.

This heuristically defined count-based bonus has been shown to be an effective unsupervised pretraining objective for RL (Campos et al., [2021](#bib.bib18)).

Machado et al. ([2020](#bib.bib43)) show the norm of learned successor features can be used to incentivize exploration as a reward bonus.

Our work differs in that we jointly maximize the entropy and learn successor features.

| | | | | | | |

| --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Algorithm | Objective | Exploration | Visual | Task | Off-policy | Pre-Trained Model |

| APT | maxH(s) | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | π(a|s),Q(s,a) |

| VISR | maxH(z)−H(z|s) | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ψ(s,z), ϕ(s) |

| MEPOL | maxH(s) | ✓⋆ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | π(a|s) |

| DIAYN | max−H(z|s)+H(a|z,s) | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | π(a|s,z) |

| EDL | maxH(s)−H(s|z) | ✓⋆ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | π(a|s,z),q(s′|s,z) |

| DADS | maxH(s)−H(s|z) | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | π(a|s,z),q(s′|s,z) |

| APS | maxH(s)−H(s|z) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ψ(s,z), ϕ(s) |

|

ψ(s): successor features, ϕ(s): state feature (i.e., the representation of states). |

Table 1: Comparing methods for pretraining RL in no reward setting. VISR (Hansen et al., [2020](#bib.bib26)), APT (Liu & Abbeel, [2021](#bib.bib42)), MEPOL (Mutti et al., [2020](#bib.bib46)), DIYAN (Eysenbach et al., [2019](#bib.bib24)), DADS (Sharma et al., [2020](#bib.bib54)), EDL (Campos et al., [2020](#bib.bib17)).

Exploration: the model can explore efficiently.

Off-policy: the model is off-policy RL.

Visual: the method works well in visual RL, e.g., Atari games.

Task: the model conditions on latent task variables z.

⋆ means only in state-based RL.

3 Preliminaries

----------------

Reinforcement learning considers the problem of finding an optimal policy for an agent that interacts with an uncertain environment and collects reward per action.

The goal of the agent is to maximize its cumulative reward.

Formally, this problem can be viewed as a Markov decision process (MDP) defined by (S,A,T,ρ0,r,γ) where

S⊆Rns is a set of ns-dimensional states,

A⊆Rna is a set of na-dimensional actions,

T:S×A×S→[0,1]

is the state transition probability distribution.

ρ0:S→[0,1] is the distribution over initial states,

r:S×A→R is the reward function, and

γ∈[0,1) is the discount factor.

At environment states s∈S, the agent take actions a∈A, in the (unknown) environment dynamics defined by the transition probability T(s′|s,a), and the reward function yields a reward immediately following the action at performed in state st.

We define the discounted return G(st,at)=∑∞l=0γlr(st+l,at+l) as the discounted sum of future rewards collected by the agent.

In value-based reinforcement learning, the agent learns learns an estimate of the expected discounted return, a.k.a, state-action value function.

| | | |

| --- | --- | --- |

| | Qπ(s,a)=Est=sat=a[∞∑l=0γlr(st+l,at+l,st+l+1)]. | |

###

3.1 Successor Features

Successor features (Dayan, [1993](#bib.bib22); Kulkarni et al., [2016](#bib.bib37); Barreto et al., [2017](#bib.bib7), [2018](#bib.bib8)) assume that there exist features ϕ(s,a,s′)∈Rd such that the reward function which specifies a task of interest can be written as

| | | |

| --- | --- | --- |

| | r(s,a,s′)=ϕ(s,a,s′)Tw, | |

where w∈Rd is the task vector that specify how desirable each feature component is.

The key observation is that the state-action value function can be decomposed as a linear form (Barreto et al., [2017](#bib.bib7))

| | | | |

| --- | --- | --- | --- |

| | Qπ(s,a) | =Est=sat=a[∞∑i=tγi−tϕ(si+1,ai+1,s′i+1)]Tw | |

| | | ≡ψπ(s,a)Tw, | |

where ψπ(s,a) are the successor features of π.

Intuitively, ψ(s,a) can be seen as a generalization of Q(s,a) to multidimensional value function with reward ϕ(s,a,s′)

Figure 2:

Diagram of the proposed method APS.

On the left shows the concept of APS, during reward-free pretraining phase, reinforcement learning is deployed to maximize the mutual information between the states induced by policy and the task variables.

During testing, the pre-trained state features can identify the downstream task by solving a linear regression problem , the pre-trained task conditioning successor features can then quickly adapt to and solve the task.

On the right shows the components of APS.

APS consists of maximizing state entropy in an abstract representation space (exploration, maxH(s)) and leveraging explored data to learn task conditioning behaviors (exploitation, max−H(s|z)).

4 Method

---------

We first introduce two techniques which our method builds upon in Section [4.1](#S4.SS1 "4.1 Variational Intrinsic Successor Features (VISR) ‣ 4 Method ‣ APS: Active Pretraining with Successor Features") and Section [4.2](#S4.SS2 "4.2 Unsupervised Active Pretraining (APT) ‣ 4 Method ‣ APS: Active Pretraining with Successor Features") and discuss their limitations.

We provide preliminary evidence of the limitations in Section [4.3](#S4.SS3 "4.3 Empirical Evidence of the Limitations of Existing Models ‣ 4 Method ‣ APS: Active Pretraining with Successor Features").

Then we propose APS in Section [4.4](#S4.SS4 "4.4 Active Pre-training with Successor Features ‣ 4 Method ‣ APS: Active Pretraining with Successor Features") to address their limitations.

###

4.1 Variational Intrinsic Successor Features (VISR)

The variational intrinsic successor features (VISR) maximizes the mutual information(I) between some policy-conditioning variable (z) and the states induced by the conditioned policy,

| | | |

| --- | --- | --- |

| | I(z;s)=H(z)−H(z|s), | |

where it is common to assume z is drawn from a fixed distribution for the purposes of training stability (Eysenbach et al., [2019](#bib.bib24); Hansen et al., [2020](#bib.bib26)).

This simplifies the objective to minimizing the conditional entropy of the conditioning variable, where s is sampled uniformly over the trajectories induced by πθ.

| | | |

| --- | --- | --- |

| | ∑z,sp(s,z)logp(z|s)=Es,z[logp(z|s)], | |

A variational lower bound is proposed to

address the intractable objective,

| | | |

| --- | --- | --- |

| | JVISR(θ)=−Es,z[logq(z|s)], | |

where q(z|s) is a variational approximation.

REINFORCE algorithm is used to learn the policy parameters by treating logq(z|s) as intrinsic reward.

The variational parameters can be optimized by maximizing log likelihood of samples.

| | |

| --- | --- |

| The passageway gridworld environments used in our experiments.

On the left, the agent needs to fetch the key first by navigating to the green location to unlock the closed passageway (shown in black). Similarly, on the right, there is an additional key-passageway pair. The agent must fetch the key (shown in purple) to unlock the upper right passageway. | The passageway gridworld environments used in our experiments.

On the left, the agent needs to fetch the key first by navigating to the green location to unlock the closed passageway (shown in black). Similarly, on the right, there is an additional key-passageway pair. The agent must fetch the key (shown in purple) to unlock the upper right passageway. |

Figure 3: The passageway gridworld environments used in our experiments.

On the left, the agent needs to fetch the key first by navigating to the green location to unlock the closed passageway (shown in black). Similarly, on the right, there is an additional key-passageway pair. The agent must fetch the key (shown in purple) to unlock the upper right passageway.

The key observation made by Hansen et al. ([2020](#bib.bib26)) is restricting conditioning vectors z to correspond to task-vectors w of the successor features formulation z≡w.

To satisfy this requirement, one can restrict the task vectors w and features ϕ(s) to be unit length and paremeterizing the discriminator q(z|s) as the Von Mises-Fisher distribution with a scale parameter of 1.

| | | |

| --- | --- | --- |

| | rVISR(s,a,s′)=logq(w|s)=ϕ(s)Tw. | |

VISR has the rapid task inference mechanism provided by successor features with the ability of mutual information maximization methods to learn many diverse behaviors in an unsupervised way.

Despite its effectiveness as demonstrated in Hansen et al. ([2020](#bib.bib26)), VISR suffers from inefficient exploration. This issue limits the further applications of VISR in challenging tasks.

###

4.2 Unsupervised Active Pretraining (APT)

The objective of unsupervised active pretraining (APT) is to maximize the entropy of the states induced by the policy, which is computed in a lower dimensional abstract representation space.

| | | |

| --- | --- | --- |

| | JAPT(θ)=H(h)=∑sp(h)logp(h),h=f(s), | |

where f:Rns→Rnh is a mapping that maps observations s to lower dimensional representations h.

In their work, Liu & Abbeel ([2021](#bib.bib42)) learns the encoder by contrastive representation learning.

With the learned representation, APT shows the entropy of h can be approximated by a particle-based entropy estimation (Singh et al., [2003](#bib.bib56); Beirlant, [1997](#bib.bib12)), which is based on the distance between each particle hi=f(si) and its k-th nearest neighbor h⋆i.

| | | |

| --- | --- | --- |

| | H(h)≈HAPT(h)∝n∑i=1log∥hi−h⋆i∥nznz. | |

This estimator is asymptotically unbiased and consistent limn→∞HAPT(s)=H(s).

It helps stabilizing training and improving convergence in practice to average over all k nearest neighbors (Liu & Abbeel, [2021](#bib.bib42)).

| | | |

| --- | --- | --- |

| | ^HAPT(h)=n∑i=1log⎛⎜⎝1+1k∑hji∈Nk(hi)∥hi−hji∥nhnh⎞⎟⎠, | |

where Nk(⋅) denotes the k nearest neighbors.

For a batch of transitions {(s,a,s′)} sampled from the replay buffer, each abstract representation f(s′) is treated as a particle and we associate each transition with a intrinsic reward given by

| | | | |

| --- | --- | --- | --- |

| | rAPT(s,a,s′) | =log⎛⎜⎝1+1k∑h(j)∈Nk(h)∥h−h(j)∥nznz⎞⎟⎠ | |

| | where h | =fθ(s′). | | (1) |

While APT achieves prior state-of-the-art performance in DeepMind control suite and Atari games, it does not conditions on latent variables (e.g. task) to capture important task information during pretraining, making it inefficient to quickly identity downstream task when exposed to task specific reward function.

Figure 4: Performance of different methods on the gridworld environments in Figure [3](#S4.F3 "Figure 3 ‣ 4.1 Variational Intrinsic Successor Features (VISR) ‣ 4 Method ‣ APS: Active Pretraining with Successor Features").

The results are recorded during testing phase after pretraining for a number of unsupervised interactions.

The success rate are aggregated over 10 random seeds.

The bottom of each bar is the zero-shot testing performance while the top is the fine-tuned performance.

###

4.3 Empirical Evidence of the Limitations of Existing Models

In this section we present two multi-step grid-world environments to illustrate the drawbacks of APT and VISR, and highlight the importance of both exploration and task inference.

The environments, implemented with the pycolab game engine (Stepleton, [2017](#bib.bib57)), are depicted shown in Figure [3](#S4.F3 "Figure 3 ‣ 4.1 Variational Intrinsic Successor Features (VISR) ‣ 4 Method ‣ APS: Active Pretraining with Successor Features"), and are fully observable to the agent.

At each episode, the agent starts from a randomly initialized location in the top left corner, with the task of navigating to the target location shown in orange.

To do so, the agent has to first pick up a key(green, purple area) that opens the closed passageway.

The easy task shown in left of Figure [3](#S4.F3 "Figure 3 ‣ 4.1 Variational Intrinsic Successor Features (VISR) ‣ 4 Method ‣ APS: Active Pretraining with Successor Features") has one key and one corresponding passageway while the hard task has two key-passageway pairs.

We evaluate the agent in terms of success rates.

During evaluation, the agent receives an intermediate reward 1 for picking up key and 10 for completing the task.

The hierarchical task presents a challenge to algorithms using only exploration bonus or successor features, as the exploratory policy is unlikely to quickly adapt to the task specific reward and the successor features is likely to never explore the space sufficiently.

Figure [4](#S4.F4 "Figure 4 ‣ 4.2 Unsupervised Active Pretraining (APT) ‣ 4 Method ‣ APS: Active Pretraining with Successor Features") shows the success rate of each method.

APT performs worse than VISR at the easy level, possibly because successor features can quickly adapt to the downstream reward.

On the other hand, APT significantly outperforms VISR at the hard level which requires a exploratory policy.

Despite the simplicity, these two gridworld environments already highlight the weakness of each method.

This observation confirms that existing formulations either fail due to inefficient exploration or slow adaption, and motivates our study of alternative methods for behavior discovery.

###

4.4 Active Pre-training with Successor Features

To address the issues of APT and VISR, we consider maximizing the mutual information between task variable (z) drawn from a fixed distribution and the states induced by the conditioned policy.

| | | |

| --- | --- | --- |

| | I(z;s)=H(s)−H(s|z). | |

The intuition is that the H(s) encourages the agent to explore novel states while H(s|z)

encourages the agent to leverage the collected data to capture task information.

Directly optimizing H(s) is intractable because the true distribution of state is unknown, as introduced in Section [4.2](#S4.SS2 "4.2 Unsupervised Active Pretraining (APT) ‣ 4 Method ‣ APS: Active Pretraining with Successor Features"), APT (Liu & Abbeel, [2021](#bib.bib42)) is an effective approach for maximizing H(s) in high-dimensional state space. We use APT to perform entropy maximization.

| | | | |

| --- | --- | --- | --- |

| | rexplorationAPS(s,a,s′) | =log⎛⎜⎝1+1k∑h(j)∈Nk(h)∥h−h(j)∥nhnh⎞⎟⎠ | |

| | where h | =fθ(s′). | | (2) |

As introduced in Section [4.1](#S4.SS1 "4.1 Variational Intrinsic Successor Features (VISR) ‣ 4 Method ‣ APS: Active Pretraining with Successor Features"), VISR (Hansen et al., [2020](#bib.bib26)) is a variational based approach for maximizing −H(z|s).

However, maximizing −H(z|s) is not directly applicable to our case where the goal is to maximize −H(s|z).

Randomly Initialize ϕ network // L2 normalized output

Randomly Initialize ψ network // dim(output)=#A×dim(W)

for *e:=1,∞* do

sample w from L2 normalized N(0,I(dim(W))) // uniform ball

Q(⋅,a|w)←ψ(⋅,a,w)⊤w,∀a∈A

for *t:=1,T* do

Receive observation st from environment

at←ϵ-greedy policy based on Q(st,⋅|w)

Take action at, receive observation st+1 and reward ~~rt~~ from environment

a′=argmaxaψ(st+1,a,w)⊤w

Compute r{APS}{}(st,a,st+1) with Equation ([4.4](#S4.Ex22 "4.4 Active Pre-training with Successor Features ‣ 4 Method ‣ APS: Active Pretraining with Successor Features")) // intrinsic reward to maxI(s;z)

y=r{APS}{}(st,a,st+1)+γψ(st+1,a′,w)⊤w

lossψ=(ψ(st,at,w)⊤w−yi)2

lossϕ=−ϕ(st)⊤w // minimize Von-Mises NLL

Gradient descent step on ψ and ϕ // minibatch in practice

end for

end for

Algorithm 1 Training APS

This intractable conditional entropy can be lower-bounded by a variational approximation,

| | | |

| --- | --- | --- |

| | F=−H(s|z)≥Es,z[logq(s|z)]. | |

This is because of the variational lower bound (Barber & Agakov, [2003](#bib.bib6)).

| | | | |

| --- | --- | --- | --- |

| | F | =∑s,zp(s,z)logp(s|z) | |

| | | =∑s,zp(s,z)logp(s|z)+∑s,zp(s,z)logq(s|z) | |

| | | −∑s,zp(s,z)logq(s|z) | |

| | | =∑s,zp(s,z)logq(s|z)+∑zp(z)DKL(p(⋅|z)||q(⋅|z)) | |

| | | ≥∑s,zp(s,z)logq(s|z) | |

| | | =Es,z[logq(s|z)] | | (3) |

Our key observation is that Von Mises-Fisher distribution is symmetric to its parametrization, by restricting z≡w similarly to VISR, the reward can be written as

| | | | |

| --- | --- | --- | --- |

| | rexploitationAPS(s,a,s′)=logq(s|w)=ϕ(s)Tw. | | (4) |

We find it helps training by sharing the weights between encoders f and ϕ.

The encoder is trained by minimizing the negative log likelihood of Von-Mises distribution q(s|w) over the data.

| | | | |

| --- | --- | --- | --- |

| | L=−Es,w[logq(s|w)]=−Es,w[ϕ(st)⊤w]. | | (5) |

Note that the proposed method is independent from the choices of representation learning for f, e.g., one can use an inverse dynamic model (Pathak et al., [2017](#bib.bib48); Burda et al., [2019](#bib.bib16)) to learn the neural encoder, which we leave for future work.

Put Equation ([2](#S4.E2 "(2) ‣ 4.4 Active Pre-training with Successor Features ‣ 4 Method ‣ APS: Active Pretraining with Successor Features")) and Equation ([4](#S4.E4 "(4) ‣ 4.4 Active Pre-training with Successor Features ‣ 4 Method ‣ APS: Active Pretraining with Successor Features")) together, our intrinsic reward can be written as

| | | |

| --- | --- | --- |

| | rAPS(s,a,s′) | |

| | =rexploitationAPS(s,a,s′)+rexplorationAPS(s,a,s′) | | (6) |

| | | |

| | where h=ϕ(s′), | | (7) |

The output layer of ϕ is L2 normalized, task vector w is randomly sampled from a uniform distribution over the unit circle.

Table [1](#S2.T1 "Table 1 ‣ 2 Related Work ‣ APS: Active Pretraining with Successor Features") positions our new approach with respect to existing ones.

Figure [2](#S3.F2 "Figure 2 ‣ 3.1 Successor Features ‣ 3 Preliminaries ‣ APS: Active Pretraining with Successor Features") shows the resulting model. Training proceeds as in other algorithms maximizing mutual information: by randomly sampling a task vector w and then trying to infer the state produced by the conditioned policy from the task vector.

Algorithm [1](#alg1 "Algorithm 1 ‣ 4.4 Active Pre-training with Successor Features ‣ 4 Method ‣ APS: Active Pretraining with Successor Features") shows the pseudo-code of APS, we highlight the changes from VISR to APS in color.

###

4.5 Implementation Details

We largely follow Hansen et al. ([2020](#bib.bib26)) for hyperparameters used in our Atari experiments, with the following three exceptions.

We use the four layers convolutional network from Kostrikov et al. ([2020](#bib.bib36)) as the encoder ϕ and f.

We change the output dimension of the encoder from 50 to 5 in order to match the dimension used in VISR.

While VISR incorporated LSTM (Hochreiter & Schmidhuber, [1997](#bib.bib30)) we excluded it for simplicity and accelerating research.

We use ELU nonlinearities (Clevert et al., [2016](#bib.bib21)) in between convolutional layers.

We do not use the distributed training setup in Hansen et al. ([2020](#bib.bib26)), after every roll-out of 10 steps, the experiences are added to a replay buffer.

This replay buffer is used to calculate all of the losses and change the weights of the network.

The task vector w is also resampled every 10 steps. We use n-step Q-learning with n=10.

Following Hansen et al. ([2020](#bib.bib26)), we condition successor features on task vector, making ψ(s,a,w) a UVFA (Borsa et al., [2019](#bib.bib14); Schaul et al., [2015](#bib.bib50)).

We use the Adam optimizer (Kingma & Ba, [2015](#bib.bib35)) with an learning rate 0.0001.

We use discount factor γ=.99.

Standard batch size of 32.

ψ is coupled with a target network (Mnih et al., [2015](#bib.bib44)), with an update period of 100 updates.

5 Results

----------

| | | | | | | | | | | |

| --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Game | Random | Human | SimPLe | DER | CURL | DrQ | SPR | VISR | APT | APS (ours) |

| Alien | 227.8 | 7127.7 | 616,9 | 739.9 | 558.2 | 771.2 | 801.5 | 364.4 | 2614.8 | 934.9 |

| Amidar | 5.8 | 1719.5 | 88.0 | 188.6 | 142.1 | 102.8 | 176.3 | 186.0 | 211.5 | 178.4 |

| Assault | 222.4 | 742.0 | 527.2 | 431.2 | 600.6 | 452.4 | 571.0 | 12091.1 | 891.5 | 413.3 |

| Asterix | 210.0 | 8503.3 | 1128.3 | 470.8 | 734.5 | 603.5 | 977.8 | 6216.7 | 185.5 | 1159.7 |

| Bank Heist | 14.2 | 753.1 | 34.2 | 51.0 | 131.6 | 168.9 | 380.9 | 71.3 | 416.7 | 262.7 |

| BattleZone | 2360.0 | 37187.5 | 5184.4 | 10124.6 | 14870.0 | 12954.0 | 16651.0 | 7072.7 | 7065.1 | 26920.1 |

| Boxing | 0.1 | 12.1 | 9.1 | 0.2 | 1.2 | 6.0 | 35.8 | 13.4 | 21.3 | 36.3 |

| Breakout | 1.7 | 30.5 | 16.4 | 1.9 | 4.9 | 16.1 | 17.1 | 17.9 | 10.9 | 19.1 |

| ChopperCommand | 811.0 | 7387.8 | 1246.9 | 861.8 | 1058.5 | 780.3 | 974.8 | 800.8 | 317.0 | 2517.0 |

| Crazy Climber | 10780.5 | 23829.4 | 62583.6 | 16185.2 | 12146.5 | 20516.5 | 42923.6 | 49373.9 | 44128.0 | 67328.1 |

| Demon Attack | 107805 | 35829.4 | 62583.6 | 16185.3 | 12146.5 | 20516.5 | 42923.6 | 8994.9 | 5071.8 | 7989.0 |

| Freeway | 0.0 | 29.6 | 20.3 | 27.9 | 26.7 | 9.8 | 24.4 | -12.1 | 29.9 | 27.1 |

| Frostbite | 65.2 | 4334.7 | 254.7 | 866.8 | 1181.3 | 331.1 | 1821.5 | 230.9 | 1796.1 | 496.5 |

| Gopher | 257.6 | 2412.5 | 771.0 | 349.5 | 669.3 | 636.3 | 715.2 | 498.6 | 2590.4 | 2386.5 |

| Hero | 1027.0 | 30826.4 | 2656.6 | 6857.0 | 6279.3 | 3736.3 | 7019.2 | 663.5 | 6789.1 | 12189.3 |

| Jamesbond | 29.0 | 302.8 | 125.3 | 301.6 | 471.0 | 236.0 | 365.4 | 484.4 | 356.1 | 622.3 |

| Kangaroo | 52.0 | 3035.0 | 323.1 | 779.3 | 872.5 | 940.6 | 3276.4 | 1761.9 | 412.0 | 5280.1 |

| Krull | 1598.0 | 2665.5 | 4539.9 | 2851.5 | 4229.6 | 4018.1 | 2688.9 | 3142.5 | 2312.0 | 4496.0 |

| Kung Fu Master | 258.5 | 22736.3 | 17257.2 | 14346.1 | 14307.8 | 9111.0 | 13192.7 | 16754.9 | 17357.0 | 22412.0 |

| Ms Pacman | 307.3 | 6951.6 | 1480.0 | 1204.1 | 1465.5 | 960.5 | 1313.2 | 558.5 | 2827.1 | 2092.3 |

| Pong | -20.7 | 14.6 | 12.8 | -19.3 | -16.5 | -8.5 | -5.9 | -26.2 | -8.0 | 12.5 |

| Private Eye | 24.9 | 69571.3 | 58.3 | 97.8 | 218.4 | -13.6 | 124.0 | 98.3 | 96.1 | 117.9 |

| Qbert | 163.9 | 13455.0 | 1288.8 | 1152.9 | 1042.4 | 854.4 | 669.1 | 666.3 | 17671.2 | 19271.4 |

| Road Runner | 11.5 | 7845.0 | 5640.6 | 9600.0 | 5661.0 | 8895.1 | 14220.5 | 6146.7 | 4782.1 | 5919.0 |

| Seaquest | 68.4 | 42054.7 | 683.3 | 354.1 | 384.5 | 301.2 | 583.1 | 706.6 | 2116.7 | 4209.7 |

| Up N Down | 533.4 | 11693.2 | 3350.3 | 2877.4 | 2955.2 | 3180.8 | 28138.5 | 10037.6 | 8289.4 | 4911.9 |

| Mean Human-Norm’d | 0.000 | 1.000 | 44.3 | 28.5 | 38.1 | 35.7 | 70.4 | 64.31 | 69.55 | 99.04 |

| Median Human-Norm’d | 0.000 | 1.000 | 14.4 | 16.1 | 17.5 | 26.8 | 41.5 | 12.36 | 47.50 | 58.80 |

| # Superhuman | 0 | N/A | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

Table 2: Performance of different methods on the 26 Atari games considered by (Kaiser et al., [2020](#bib.bib33)) after 100K environment steps. The results are recorded at the end of training and averaged over 5 random seeds for APS. APS outperforms prior methods on all aggregate metrics, and exceeds expert human performance on 8 out of 26 games while using a similar amount of experience.

We test APS on the full suite of 57 Atari games (Bellemare et al., [2013](#bib.bib13)) and the sample-efficient Atari setting (Kaiser et al., [2020](#bib.bib33); van Hasselt et al., [2019](#bib.bib58)) which consists of the 26 easiest games in the Atari suite (as judged by above random performance for their algorithm).

We follow the evaluation setting in VISR (Hansen et al., [2020](#bib.bib26)) and APT (Liu & Abbeel, [2021](#bib.bib42)), agents are allowed a long unsupervised training phase (250M steps) without access to rewards, followed by a short test phase with rewards.

The test phase contains 100K environment steps – equivalent to 400k frames, or just under two hours – compared to the typical standard of 500M environment steps, or roughly 39 days of experience.

We normalize the episodic return with

respect to expert human scores to account for different scales of scores in each game, as done in previous works.

The human-normalized performance of an agent on a game is calculated as agent score−random scorehuman score−random %

score and aggregated across games by mean or median.

When testing the pre-trained successor features ψ, we need to find task vector w from the rewards. To do so, we rollout 10 episodes (or 40K steps, whichever comes first) with the trained APS, each conditioned on a task vector chosen uniformly on a 5-dimensional sphere. From these initial episodes, we combine the data across all episodes and solve the linear regression problem.

Then we fine-tune the pre-trained model for 60K steps with the inferred task vector, and the average returns are compared.

A full list of scores and aggregate metrics on the Atari 26 subset is presented in Table [2](#S5.T2 "Table 2 ‣ 5 Results ‣ APS: Active Pretraining with Successor Features").

The results on the full 57 Atari games suite is presented in Supplementary Material.

For consistency with previous works, we report human and random scores from (Hessel et al., [2018](#bib.bib29)).

In the data-limited setting, APS achieves super-human performance on eight games and achieves scores higher than previous state-of-the-arts.

In the full suite setting, APS achieves super-human performance on 15 games, compared to a maximum of 12 for any previous methods and achieves scores significantly higher than any previous methods.

6 Analysis

-----------

#### Contribution of Exploration and Exploitation

Figure 5: Scores of different methods and their variants on the 26 Atari games considered by Kaiser et al. ([2020](#bib.bib33)). X→Y denotes training method Y using the data collected by method X at the same time.

In order to measure the contributions of components in our method, we aim to answer the following two questions in this ablation study.

Compared with APT (maxH(s)), is the improvement solely coming from better fast task solving induced by max−H(s|z) and the exploration is the same?

Compared with VISR (maxH(z)−H(z|s)), is the improvement solely coming from better exploration due to maxH(s)−H(s|z) and the task solving ability is the same?

We separate Atari 26 subset into two categories. Dense reward games in which exploration is simple and exploration games which require exploration.

In addition to train the model as before, we simultaneously train another model using the same data, e.g. {APS}→APT denotes when training APS simultaneously training APT using the same data as APS.

As shown in Figure [5](#S6.F5 "Figure 5 ‣ Contribution of Exploration and Exploitation ‣ 6 Analysis ‣ APS: Active Pretraining with Successor Features"), on dense reward games, {APS}→APT performs better than APT→{APS}.

On exploration games, {APS}→APT significantly outperforms APT→{APS}.

Similarly {APS}→VISR performs better than the other way around.

Together, the results indicate that entropy maximization and variational successor features improves each other in a nontrivial way, and both are important to the performance gain of APS.

| | |

| --- | --- |

| Variant | Human-Normalized Score |

| | mean | median |

| APS | 99.04 | 58.80 |

| APS w/o fine-tune | 81.41 | 49.18 |

| VISR (controlled, w/ fine-tune) | 68.95 | 31.87 |

| APT (controlled, w/o fine-tune) | 58.23 | 19.85 |

| APS w/o shared encoder | 87.59 | 51.45 |

Table 3: Scores on the 26 Atari games for variants of APS, VISR, and APT. Scores of considered variants are averaged over 3 random seeds.

#### Fine-Tuning Helps Improve Performance

We remove fine-tuning from APS that is we evaluate its zero-shot performance, the same as in Hansen et al. ([2020](#bib.bib26)).

We also employ APS’s fine-tuning scheme to VISR, namely 250M (without access to rewards, followed by a short task identify phase (40K steps) and a fine-tune phase (60K steps).

The results shown in Table [3](#S6.T3 "Table 3 ‣ Contribution of Exploration and Exploitation ‣ 6 Analysis ‣ APS: Active Pretraining with Successor Features") demonstrate that fine-tuning can boost performance.

APS w/o fine-tune outperforms all controlled baselines, including VISR w/ fine-tune.

#### Shared Encoder Can Boost Data-Efficiency

We investigate the effect of using ϕ as the encoder f.

To do so, we consider a variant of APS that learns the encoder f as in APT by contrastive representation learning.

The performance of this variant is denoted as APS w/o shared encoder shown in Table [3](#S6.T3 "Table 3 ‣ Contribution of Exploration and Exploitation ‣ 6 Analysis ‣ APS: Active Pretraining with Successor Features").

Sharing encoder can boost data efficiency, we attribute the effectiveness to ϕ better captures the relevant information which is helpful for computing intrinsic reward.

We leave the investigation of using other representation learning methods as future work.

7 Conclusion

-------------

In this paper, we propose a new unsupervised pretraining method for RL.

It addresses the limitations of prior mutual information maximization-based and entropy maximization-based methods and combines the best of both worlds.

Empirically, APS achieves state-of-the-art performance on the Atari benchmark, demonstrating significant improvements over prior work.

Our work demonstrates the benefit of leveraging state entropy maximization data for task-conditioned skill discovery.

We are excited about the improved performance by decomposing mutual information as H(s)−H(s|z) and optimizing them by particle-based entropy and variational successor features.

In the future, it is worth studying how to combine approaches designed for maximizing the alternative direction −H(z|s) with the particle-based entropy maximization.

8 Acknowledgment

-----------------

We thank members of Berkeley Artificial Intelligence Research (BAIR) Lab for many insightful discussions.

This work was supported by Berkeley Deep Drive, the Open Philanthropy Project, and Intel.

|

abe5510c-dfbf-4cff-a9de-99c9f1666719

|

StampyAI/alignment-research-dataset/lesswrong

|

LessWrong

|

Is Global Reinforcement Learning (RL) a Fantasy?

In general, the idea of ensuring AI safety is great (I do a lot of work on that myself), but I have a problem with people asking for donations so they can battle ***nonexistent*** threats from AI.

Many people are selling horror stories about the terrible things that could happen when AIs become truly intelligent - and those horror stories frequently involve the idea that *even if* we go to enormous lengths to build a safe AI, and *even if* we think we have succeeded, those pesky AIs will wriggle out from under the safety net and become psychopathic monsters anyway.

To be sure, future AIs might do something other than what we expect - so the general principle is sound - but the sad thing about these horror stories is that if you look closely you will find they are based on a set of astonishingly bad assumptions about how the supposed AIs of the future will be constructed. The worst of these bad assumptions is the idea that AIs will be controlled by something called "reinforcement learning" (frequently abbreviated to "RL").

>

> WARNING! If you already know about reinforcement learning, I need you to be absolutely clear that what I am talking about here is the use of RL at the ***global-control level***of an AI. I am not talking about RL as it appears in relatively small, local circuits or adaptive feedback loops. There has already been much confusion about this (with people arguing vehemently that RL has been applied here, there, and all over the place with great success). RL does indeed work in limited situations where the reward signal is clear and the control policies are short(ish) and not too numerous: the point of this essay is to explain that when it comes to AI safety issues, RL is assumed at or near the global level, where reward signals are virtually impossible to find, and control policies are both gigantic (sometimes involving actions spanning years) and explosively numerous.

>

>

>

EDIT: In the course of numerous discussions, one question has come up so frequently that I have decided to deal with it here in the essay. The question is: "You say that RL is used almost ubiquitously as the architecture behind these supposedly dangerous AI systems, and yet I know of many proposals for dangerous AI scenarios that do not talk about RL."

In retrospect this is a (superficially) fair point, so I will clarify what I meant.

All of the architectures assumed by people who promote these scenarios have a core set of fundamental weaknesses (spelled out in my 2014 AAAI Spring Symposium paper). Without repeating that story here, I can summarize by saying that those weaknesses lead straight to a set of solutions that are manifestly easy to implement. For example, in the case of Steve Omohundro's paper, it is almost trivial to suggest that for ALL of the types of AI he considers, he has forgotten to add a primary supergoal which imposes a restriction on the degree to which "instrumental goals" are allowed to supercede the power of other goals. At a stroke, every problem he describes in the paper disappears, with the single addition of a goal that governs the use of instrumental goals -- the system cannot say "If I want to achieve goal X I could do that more efficiently if I boosted my power, so therefore I should boost my power to cosmic levels first, and then get back to goal X." This weakness is so pervasive that I can hardly think of a popular AI Risk scenario that is not susceptible to it.

However, in response to this easy demolition of those weak scenarios, people who want to salvage the scenarios invariably resort to claims that the AI could be developing its intelligene through the use of RL, completely independently of all human attempts to design the control mechanism. By this means, these people eliminate the idea that there is any such thing as a human programmer who comes along and writes the supergoal which stops the instrumental goals from going up to the top of the stack.

This maneuver is, in my experience of talking to people about such scenarios, utterly universal. I repeat: every time they are backed into a corner and confronted by the manifestly easy solutions, they AMEND THE SCENARIO TO MAKE THE AI CONTROLLED BY REINFORCEMENT LEARNING.

That is why I refer to reinforcement learning as the one thing that all these AI Risk scenarios (the ones popularized by MIRI, FHI, and others) have as a fundamental architectural assumption.

Okay, that is the end of that clarification. Now back to the main line of the paper...

I want to set this essay in the context of some important comments about AI safety made by Holden Karnofsky at openphilanthropy.org. Here is his take on one of the "challenges" we face in ensuring that AI systems do not become dangerous:

>

> *Going into the details of these challenges is beyond the scope of this post, but to give a sense for non-technical readers of what a relevant challenge might look like, I will elaborate briefly on one challenge. A reinforcement learning system is designed to learn to behave in a way that maximizes a quantitative “reward” signal that it receives periodically from its environment - for example, [DeepMind’s Atari player](https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~vmnih/docs/dqn.pdf) is a reinforcement learning system that learns to choose controller inputs (its behavior) in order to maximize the game score (which the system receives as “reward”), and this produces very good play on many Atari games. However, if a future reinforcement learning system’s inputs and behaviors are not constrained to a video game, and if the system is good enough at learning, a new solution could become available: the system could maximize rewards by directly modifying its reward “sensor” to always report the maximum possible reward, and by avoiding being shut down or modified back for as long as possible. This behavior is a formally correct solution to the reinforcement learning problem, but it is probably not the desired behavior. And this behavior might not emerge until a system became quite sophisticated and had access to a lot of real-world data (enough to find and execute on this strategy), so a system could appear “safe” based on testing and turn out to be problematic when deployed in a higher-stakes setting. The challenge here is to design a variant of reinforcement learning that would not result in this kind of behavior; intuitively, the challenge would be to design the system to pursue some actual goal in the environment that is only indirectly observable, instead of pursuing problematic proxy measures of that goal (such as a “hackable” reward signal).*

>

>

>

My focus in the remainder of this essay is on the sudden jump from DeepMind's Atari game playing program to the fully intelligent AI capable of outwitting humanity. They are assumed to both involve RL. The extrapolation of RL to the global control level in a superintelligent AI is unwarranted, and that means that this supposed threat is a fiction.

What Reinforcement Learning is.

-------------------------------

Let's begin by trying to explain what "reinforcement learning" (RL) actually is. Back in the early days of Behaviorism (which became the dominant style of research in psychology in the 1930s) some researchers decided to focus on simple experiments like putting a rat into a cage with a lever and a food-pellet dispenser, and then connecting these two things in such a way that if the rat pressed the lever, a pellet would be dispensed. Would the rat notice this? Of course it did, and soon the rat would be spending inordinate amounts of time just pressing the lever, whether food came out or not.

What the researchers did next was to propose that the only thing of importance "inside" the rat's mind was a set of connections between behaviors (e.g. pressing the lever), stimuli (e.g a visual image of the lever) and rewards (e.g. getting a food pellet). Critical to all of this was the idea that if a behavior was followed by a reward, a direct connection between the two would be strengthened in such a way that future behavior choices would be influenced by that strong connection.

That is reinforcement learning: you "reinforce" a behavior if it appears to be associated with a reward. What these researchers really wanted to claim was that this mechanism could explain everything important going on inside the rat's mind. And, with a few judicious extensions, they were soon arguing that the same type of explanation would work for the behavior of all "thinking" creatures.

I want you to notice something very important buried in this idea. The connection between the two reward and action is basically a single wire with a strength number on it. The rat does not weigh up a lot of pros and cons; it doesn't think about anything, does not engage in any problem solving or planning, does not contemplate the whole idea of food, or the motivations of the idiot humans outside the cage. The rat is not supposed to be capable of any of that: it just goes *bang!* lever-press, *bang!* food-pellet-appears, *bang!* increase-strength-of-connection.

The Demise of Reinforcement Learning

------------------------------------

Now let's fast forward to the 1960s. Cognitive psychologists are finally sick and tired of the ridiculousness of the whole Behaviorist programme. It might be able to explain the rat-pellet-lever situation, but for anything more complex, it sucks. Behaviorists have spent decades engaging in all kinds of mental contortionist tricks to argue that they would eventually be able to explain all of human behavior without using much more than those direct connections between stimuli, behaviors and rewards ... but by 1960 the psychology community has stopped believing that nonsense, because it never worked.

Is it possible to summarize the main reason why they rejected it? Sure. For one thing, almost all realistic behaviors involve rewards that arrive long after the behaviors that cause them, so there is a gigantic problem with deciding which behaviors should be reinforced, for a given reward. Suppose you spend years going to college, enduring hard work and very low-income lifestyle. Then years later you get a good job and pay off your college loan. Was this because, like the rat, you happened to try the *going-to-college-and-suffering-poverty* behavior many times before, and the first time you tried it you got a *good-job-that-paid-off-your-loan* reward? And was it the case that you noticed the connection between reward and behavior (uh ... how did you do that, by the way? the two were separated in time by a decade!), and your brain automatically reinforced the connection between those two?

A More Realistic Example

------------------------

Or, on a smaller scale, consider what you are doing when you sit in the library with a mathematics text, trying to solve equations. What reward are you seeking? A little dopamine hit, perhaps? (That is the modern story that neuroscientists sell).

Well, maybe, but let's try to stay focused on the precise idea that the Behaviorists were trying to push: that original rat was emphatically NOT supposed to do lots of thinking and analysis and imagining when it decided to push the lever, it was supposed to ***push the lever by chance***, and ***then*** it happened to notice that a reward came.

The whole point of the RL mechanism is that the intelligent system doesn't engage in a huge, complex, structured analysis of the situation, when it tries to decide what to do (if it did, the explanation for why the creature did what it did would be in the analysis itself, after all!). Instead, the RL people want you to believe that the RL mechanism did the heavy lifting, and that story is absolutely critical to RL. The rat simply tries a behavior at random - with no understanding of its meaning - and it is only because a reward then arrives, that the rat decides that in the future it will go press the lever again.